Inflation rose by 3.6 per cent in the twelve months to October. This was better than the 3.8 per cent figure registered in September – but still far higher than the Bank of England’s 2 per cent target.

The number was dragged higher by food and non-alcoholic beverage prices, which rose 4.9 per cent on the year. Services inflation was also elevated in October, despite softening to 4.5 per cent from 4.7 per cent the previous month. With rate-setters at the Bank of England split on what to do next, these details really matter.

Doves on the committee think that there is already evidence of slack in the economy. But a rival camp is concerned about inflation expectations and the risk of second-round effects: if people expect high inflation and try to beat it with high wage and price demands,, a dangerous spiral can set in. James Smith, developed market economist at ING, described last month’s food inflation figures as “red meat for the hawks”.

Read more from Investors’ Chronicle

Some prices shape our inflation expectations more than others. Most of us would struggle to say how much sofa prices have risen over the past twelve months (0.3 per cent, as it turns out). But we track food costs far more closely. We buy it regularly, have a sense of typical prices, and can’t postpone our consumption when costs rise. Bank of England governor Andrew Bailey noted this summer that food prices are “salient”, and highlighted their ability to trigger second-round effects. An unaffordable food shop is a powerful incentive to ask for a pay rise.

Pressure from services inflation is also a concern – even though the latest numbers moved in the right direction. In its November Monetary Policy Report, BoE rate-setters said that at least some of the overshoot was caused by decisions made in last year’s Budget. Higher employer national insurance contributions in particular have been passed on to services prices.

At the time of writing Budget decisions were still unknown, but Reeves appeared to be at pains to avoid any more inflationary moves. At the start of the month, she stressed that the choices in the Budget would be “focused on getting inflation falling and creating the conditions for interest rate cuts to support economic growth and improve the cost of living” – albeit this was before plans to raise income tax (a disinflationary move) were scrapped.

Will the Bank of England cut rates next month?

Bar any big surprises (a risky thing to write in a week with a Budget in it), the BoE should be on track to cut interest rates next month. Analysts at Pantheon Macroeconomics think that the hurdle to data preventing a December cut is now “very high”, driven by weak economic data, and weak employment figures which are leading to wage growth easing back. But they expect a more extended pause after that. Analysts at Société Générale think that tax hikes introduced in the Budget will dampen inflation – albeit not enough to justify further action in February. They expect the first cut of 2026 to fall in April next year.

Economists are increasingly confident that price growth has peaked and will trend downwards from now on – but it could take a while to reach the 2 per cent target. Economists at the NIESR think-tank expect inflation to remain above 3 per cent for the next six months, allowing the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) to make two cautious rate cuts next year.

Why high inflation matters

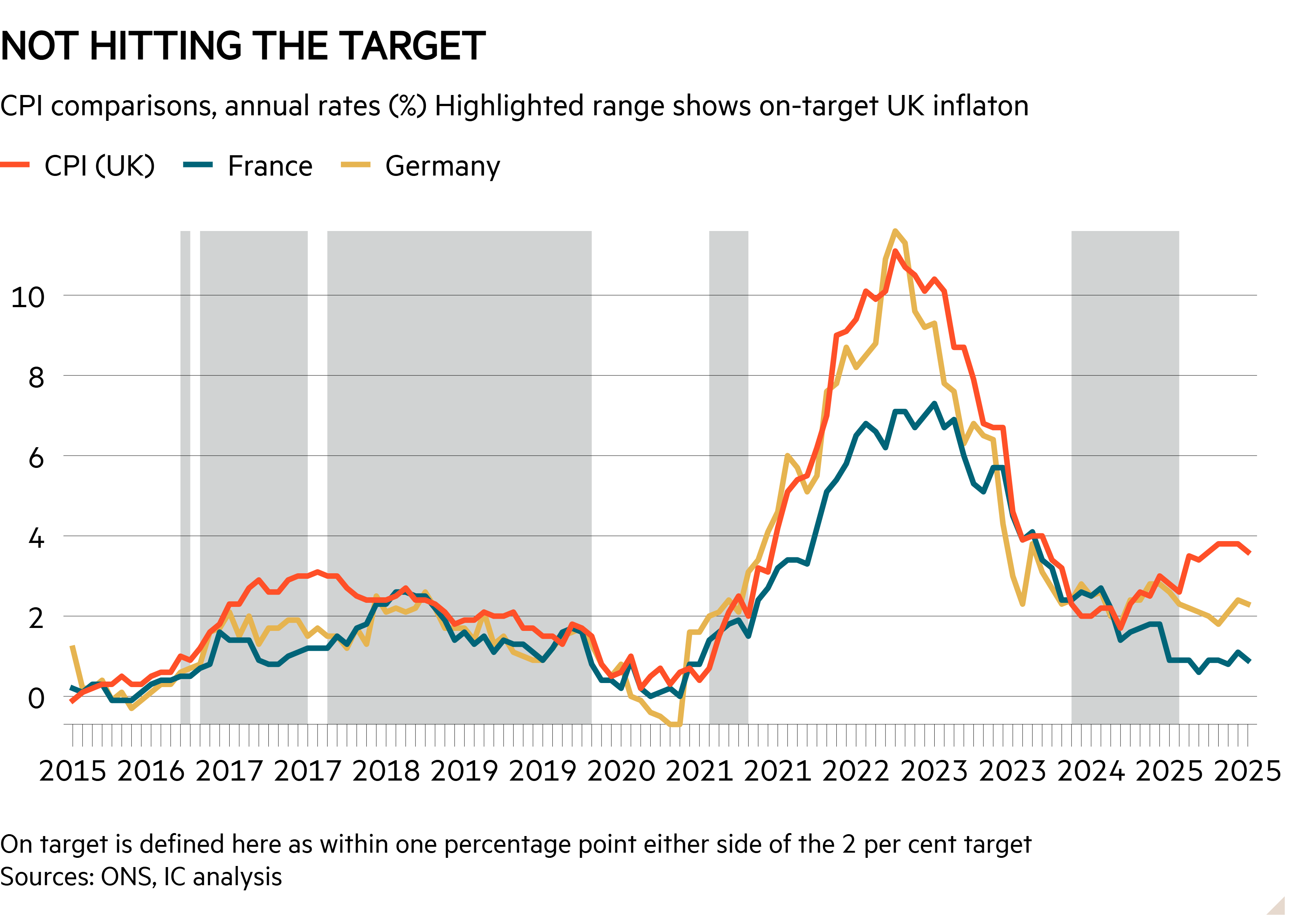

As the chart below shows, UK price growth remains high by European standards. This matters to the government: gilt yields are pushed up by rising inflation expectations, and even small increases in those yields cost the government billions in interest costs.

We may have become hardened by our recent experiences of double-digit inflation, but today’s rate is still a concern. At 2 per cent it takes 36 years for prices to double; at 3.6 per cent, they do so in just 21. This gap forces us to run much faster to outpace inflation, whether through price and wage demands or higher investment returns.

If these pressures begin to shape expectations, second-round effects and inflationary spirals could follow. The unshaded areas on the chart above show that inflation has been ‘off target’ for huge swathes of the past ten years (and that’s when we define ‘on target’ as between 1 and 3 per cent). This is a less than ideal record for the BoE, and has forward-looking consequences, too. People are less likely to expect low and stable 2 per cent inflation if they haven’t experienced it.