China’s iron grip on rare earths — from the mines to the magnets — is the product of a deliberate, decades-long campaign that today hands Beijing a devastating trump card in its showdown with Washington.

These 17 obscure elements are the lifeblood of tomorrow’s economy: electric vehicles, wind turbines, smartphones, MRI machines, and virtually every advanced weapon system — from F-35 jets and missile guidance to laser targeting and stealth coatings.

Western efforts to build alternative supply chains are underway, but analysts agree it will take 7–15 years and tens of billions of dollars before the United States and its allies can loosen China’s chokehold. Until then, the world’s most critical materials remain under one country’s thumb.

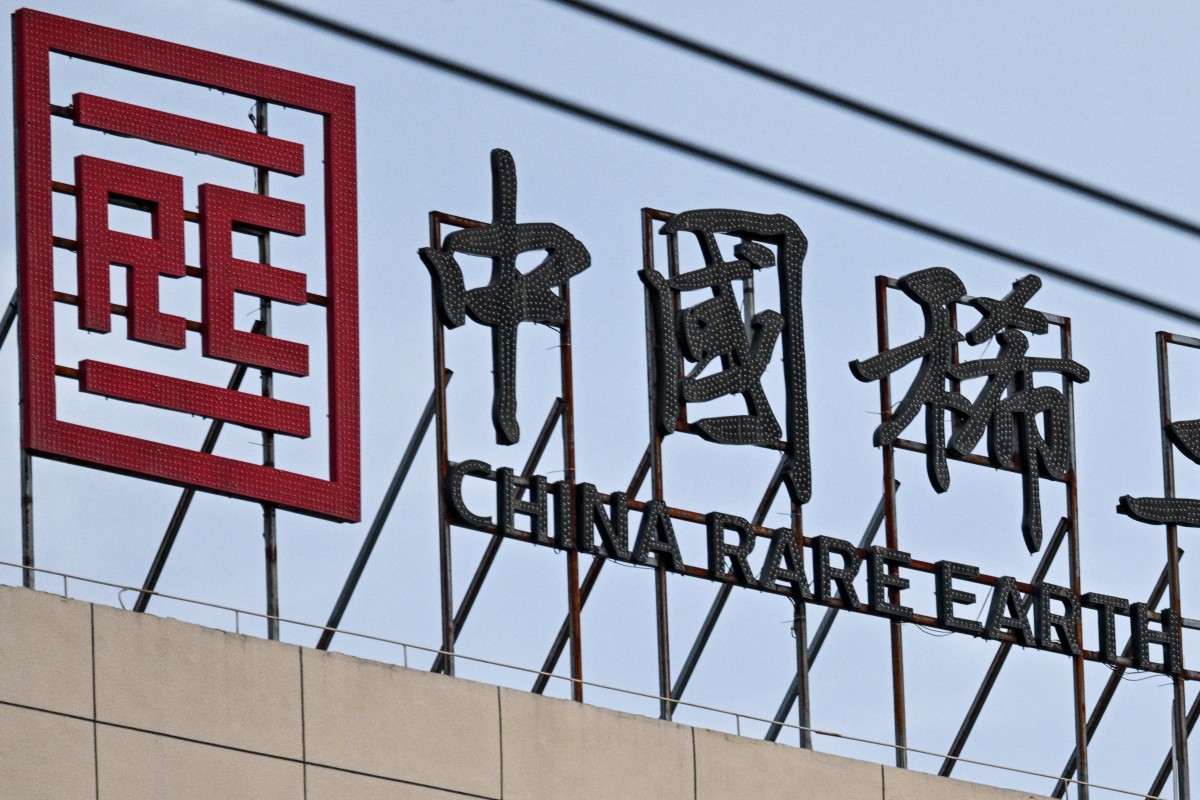

Sprawling new headquarters are being built in Ganzhou for China Rare Earth Group, one of the country’s two largest state-owned companies in the industry, following years of consolidation directed by Beijing.

Challenges this year have “paved the way for more countries to look into expanding rare earth metal production and processing”, Heron Lim, economics lecturer at ESSEC Business School, told AFP.

“This investment could pay longer-term dividends,” he said.

The logo and signage of the China Rare Earth Group is seen at its processing plant in Longnan county, Ganzhou, in eastern China’s Jiangxi province on November 20, 2025. China’s stranglehold on the rare earths industry — from natural reserves and mining through processing and innovation — is the result of a decades-long drive, now giving Beijing crucial leverage in its trade war with the United States. (Photo by Hector RETAMAL / AFP) / TO GO WITH AFP STORY CHINA-US-TECHNOLOGY-DIPLOMACY-MINING, YEARENDER BY PETER CATTERALL

The logo and signage of the China Rare Earth Group is seen at its processing plant in Longnan county, Ganzhou, in eastern China’s Jiangxi province on November 20, 2025. China’s stranglehold on the rare earths industry — from natural reserves and mining through processing and innovation — is the result of a decades-long drive, now giving Beijing crucial leverage in its trade war with the United States. (Photo by Hector RETAMAL / AFP) / TO GO WITH AFP STORY CHINA-US-TECHNOLOGY-DIPLOMACY-MINING, YEARENDER BY PETER CATTERALL

Trade War

In early October, Beijing slammed sweeping export controls on rare earths, sending panic through global factories and instantly freezing billions of dollars in high-tech production lines.

The move landed like a precision strike in Washington, where Trump’s second-term trade war had just reignited. Within weeks, it forced the White House to the table.

At last month’s high-stakes summit in South Korea, Trump and Xi signed a fragile one-year truce that guarantees continued rare-earth flows and suspends America’s most punishing tariffs.

The agreement is already being hailed in Beijing as a clear win: China surrendered nothing permanent, kept its chokehold intact, and bought itself another year to widen an already unassailable lead.

“Rare earths are likely to remain at the centre of future Sino-US economic negotiations despite the tentative agreements thus far,” Heron Lim told AFP.

“China has demonstrated its willingness to use more trade levers to keep the United States at the negotiating table,” he said.

“The turbulence has created a challenging environment for producers that rely on various rare earth metals, as near-term supply is uncertain.”

Washington and its allies are now racing to develop alternative mining and processing chains, but experts warn that the process will take years.

Supremacy Surrendered

During the Cold War, the United States led the way in developing abilities to extract and process rare earths, with the Mountain Pass mine in California providing the bulk of global supplies.

But as tensions with Moscow eased and the substantial environmental toll of the rare-earth industry came into prominence, the United States gradually offshored capacity in the 1980s and 1990s.

Now, China controls most of the global rare earths mining — around two-thirds, by most estimates.

It is already home to the world’s largest natural reserves of the elements of any country, according to geological surveys.

And it has a near-total monopoly on separation and refining, with analysis this year showing a share of around 9/10 of all global processing.

Furthermore, a commanding lead in patents and strict export controls on processing technology solidify Beijing’s efforts to prevent know-how from leaving the country.

“The United States and the European Union are heavily reliant on imports of rare earth elements, underscoring significant risks to critical industries,” said Amelia Haines, commodities analyst at BMI, at a seminar this month.

“This sustained risk is likely to catalyse a faster, broader pivot towards rare earth security,” she said.

US defence authorities have in recent years directed large sums towards shoring up domestic production — part of efforts to achieve a “mine-to-magnet” supply chain by 2027.

Washington has also been working with allies to develop extraction and processing alternatives to China.

Trump signed a rare earths deal last month, promising $8.5 billion in critical minerals projects with Prime Minister Anthony Albanese of Australia — a country with vast territory home to extensive rare earth resources.

The US president also signed cooperation deals with Japan, Malaysia, and Thailand last month covering the critical minerals sector.

Despite the flurry of activity and headlines this year, Washington has been aware of its rare earths problem for years.

In 2010, a maritime territorial dispute with Tokyo prompted Beijing to suspend shipments of the minerals to Japan — the first major incident highlighting geopolitical ramifications of China’s control over the sector.

The episode prompted the Obama administration to call for strengthening US domestic resilience in the strategic field. But 15 years later, China remains the chief producer of rare earths.

By Agence France-Presse

Edited by EurAsian Times Online Desk