There is this conventional wisdom in Western Europe that their economies are the role models for Eastern Europe. That was certainly the case 35 years ago when the Berlin Wall fell and took the Soviet Empire with it into the grave. However, today the relationship between Poland and the West has flipped. While the Poles continue to see steady improvements in their standard of living, countries in Western Europe are battling economic stagnation.

What has Poland done to avoid the stagnation curse of the West?

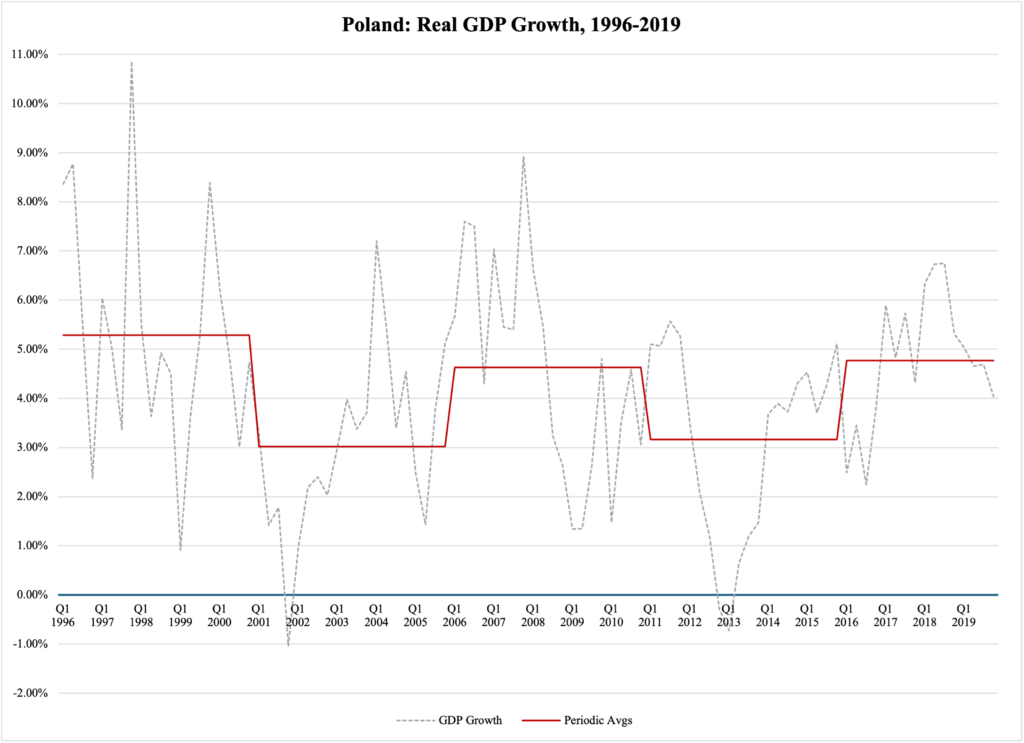

To start with the standard macroeconomic variable, GDP, Figure 1 reports annual inflation-adjusted growth rates (reported quarterly) from 1996 through 2019. This is the formative period where Poland transitioned from a post-Soviet economy into a modern, Western industrialized powerhouse. Although the growth rate fluctuated quite a bit in the early years of the period, a more stable business cycle emerged about a decade into this century:

Figure 1

Source of raw data: Eurostat

Source of raw data: Eurostat

There is remarkable strength in the growth rates of the Polish economy: as the red function explains with its five segments, over the long term Poland has seen its economy grow by 3% or more. This is a healthy rate that allows the country to enjoy a steadily rising standard of living; although the Polish economy has not grown as quickly in recent years, its GDP per capita—the base variable for any standard-of-living comparison—has grown more than twice as fast as many other countries in the European Union.

For example, from 1996 through 2023, measured in U.S. dollars, Polish GDP per capita

Increased 2.1 times faster than the Swedish GDP per capita;

Increased 1.9 times faster than the German equivalent.

Both these numbers are adjusted for inflation.

As mentioned, GDP growth in Poland has slowed down in the last couple of years. From 2023 through the second quarter of 2025, real economic growth averaged 1.9% per year—a significant slowdown from the averages reported in Figure 1 above.

This slowdown coincides relatively well with Donald Tusk taking over as prime minister. To what extent his policies are directly responsible for the slowdown in GDP growth is a matter for a closer examination when more economic data is available. Until then, let us focus on two reasons for this slowdown, both of which are found in the deeper layers of the GDP data.

To begin with, private consumption slowed down: in 2023, when the effects of the pandemic-related artificial economic shutdowns were fully gone, Polish consumers went about their spending more cautiously than they had prior to the pandemic outbreak in 2020. While private consumption grew by 3.2% per year in real terms in 2011-2019, its growth has averaged 1.8% per year since 2023.

Private consumption accounts for 56% of the Polish economy. This is low compared to most other industrialized countries, but it is still a large enough part that when spending growth tapers off by such big numbers as we are looking at here, there is no way to avoid impact on the economy as a whole.

In addition to weaker private consumption—or household spending—Poland has experienced a major slowdown in its exports. From 2011 to 2019, sales of Polish goods and services to other countries increased by 6.6% per year, again in real terms; since 2023, the annual increase has been a tepid 2.5%.

Despite these concerning numbers, unemployment remains manageable: in September, 13.8% of Poland’s youth—aged 24 or lower—were involuntarily unemployed; only seven countries in the EU did better. As far as the rest of the workforce is concerned, only 2.5% of those aged 25 and older were unemployed. This ranks Poland as one of the five best in Europe, with Malta and Slovenia a tad better at 2.4%, Czechia sharing the Polish rate, and Bulgaria coming in at 2.6%.

There is more good news, despite the weakening in GDP growth. Polish businesses keep increasing their capital formation at strong rates: 4.8% per year since 2023, which is only moderately down from 5.2% per year in 2011-2019.

Government spending is also rising at rapid rates. The reasons for this are not relevant here; the question is how much more the public sector can outpace private sector activity without causing a structural imbalance in the economy. Such an imbalance occurs when the private, i.e., tax-paying sector is no longer able to fund government on an ongoing basis.

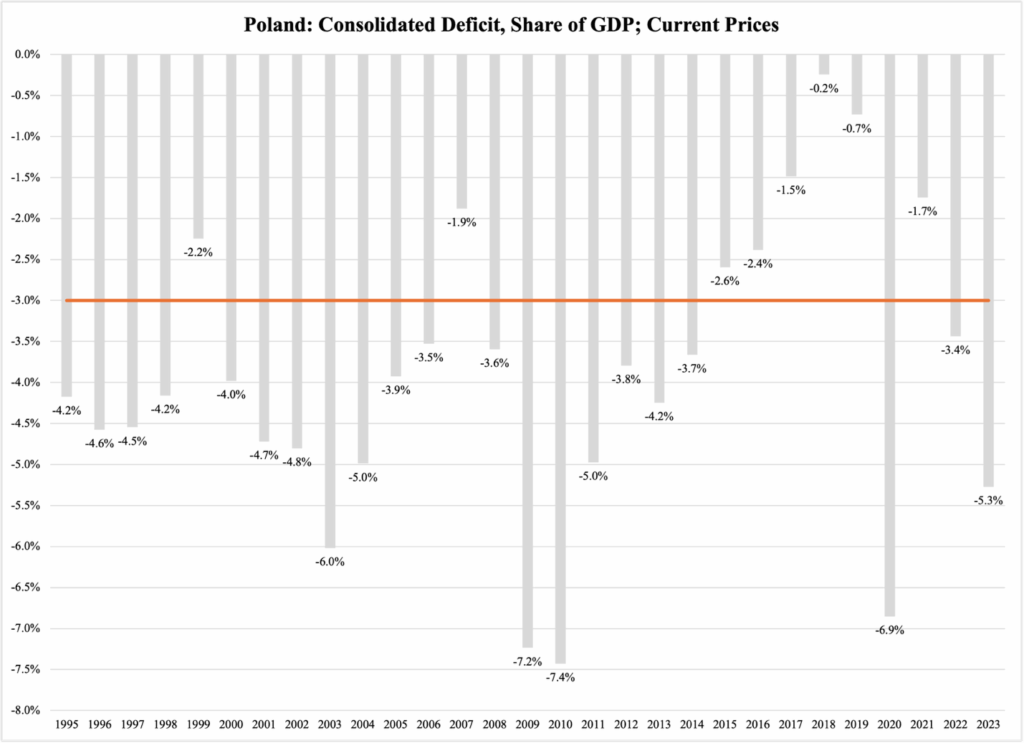

Poland is not there yet. Its public finances are in acceptable shape; as Figure 2 reports, they have a long, so far unbroken streak of budget deficits (since 1996), but those budget shortfalls gradually became smaller in the 2010s:

Figure 2

Source of raw data: Eurostat

Source of raw data: Eurostat

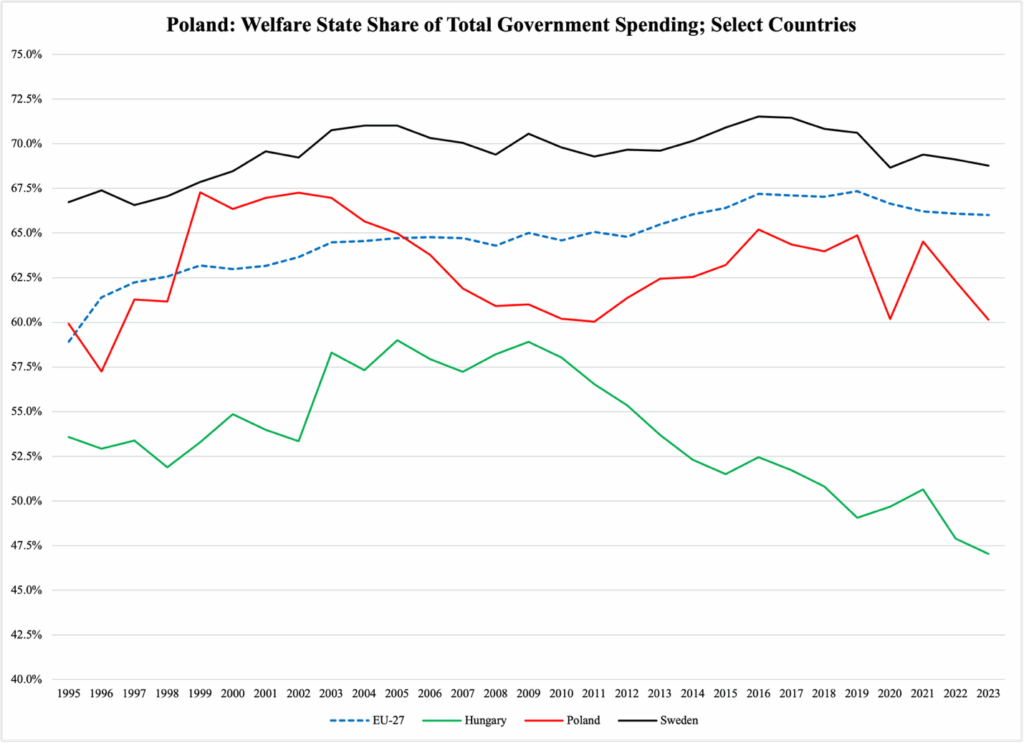

This deficit record resembles that of Hungary, though with somewhat worse numbers. In both cases, though, the annual borrowing has not led to any catastrophic developments of public finances. The reason is that both Poland and Hungary exercise a certain level of moderation when it comes to the deficit-driving spending structure we also know as the welfare state. The Poles have made the choice to keep their welfare state at a level moderately below the EU average:

Figure 3

Source of raw data: Eurostat

Source of raw data: Eurostat

The welfare state drives budget deficits because of its redistributive nature: under normal European definitions of social benefits, namely that they should reduce differences between citizens in income, consumption, and growth, the welfare state discourages work and encourages dependency on government handouts. When configured this way, the welfare state slows down economic growth; Sweden is a tragic example of this phenomenon.

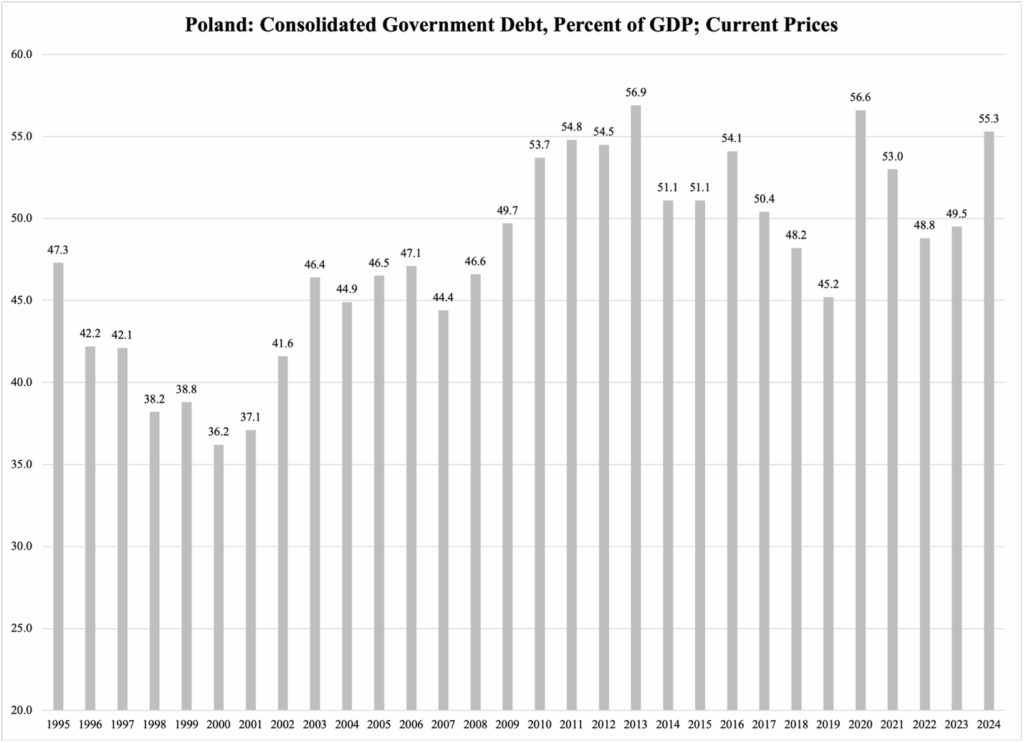

Since Poland maintains a welfare state below the EU average, it can expect a little bit more in annual GDP growth than most other welfare states can. This also contributes to keeping the Polish government’s debt under control:

Figure 4

Source of raw data: Eurostat

Source of raw data: Eurostat

All in all, the Polish economy is in good but not excellent shape. The slowdown in GDP growth and the rise in budget deficits as a share of GDP (Figure 2 above) could become a problem for the government. At the same time, all is not bad in the private sector: in addition to moderate unemployment—at least by European standards—capital formation is at excellent rates.

Unless there is any unpleasant shift for the worse, the Polish economy should pick up speed again during the course of next year.