WANA (Nov 27) – Tehran’s official tone on nuclear talks in recent weeks has appeared calm, calculated, and even “open to dialogue.” Yet the reality on the ground resembles something closer to a deliberate suspension. The military confrontation between Iran, the United States, and Israel during the 12-day conflict in June not only derailed the partial negotiations of 2025, but pushed the diplomatic environment into what can be called a “post-negotiation phase”—a stage where everyone talks about negotiations, but no one actually negotiates.

When the four main ambiguities highlighted in recent weeks are considered together, a clearer picture emerges of how Tehran is seeking to retain narrative control.

1) The halt in talks: neither Iran’s decision nor a U.S. initiative—rather, a consequence of war

A candid interview on Wednesday by Seyed Abbas Araghchi with France24 revealed a key point: The negotiations are currently on hold because, after the June strikes, the United States has shown no real willingness to engage.

In Iran’s official narrative, the pause is a forced decision, not a voluntary one. Tehran argues that after joint U.S.–Israeli attacks on nuclear facilities, Washington cannot expect Iran to remain at the negotiating table without offering a clear explanation for its military behavior. This position is significant for several reasons:

WANA (Nov 26) – The Secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council stated that the Americans attempt to present themselves as the pivotal force behind every global development, but this is merely self-deception. Ali Larijani, the Secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, in a post on social media platform X (formerly Twitter), wrote: […]

Iran views the June attack as part of the history of nuclear negotiations, not a separate event.

The pause represents a “structural protest,” not a tactical move—Tehran seeks a redefinition of the relationship, not merely adjustments within a deal.

Put simply: Iran has not halted negotiations; it has halted the U.S. version of what negotiations should look like.

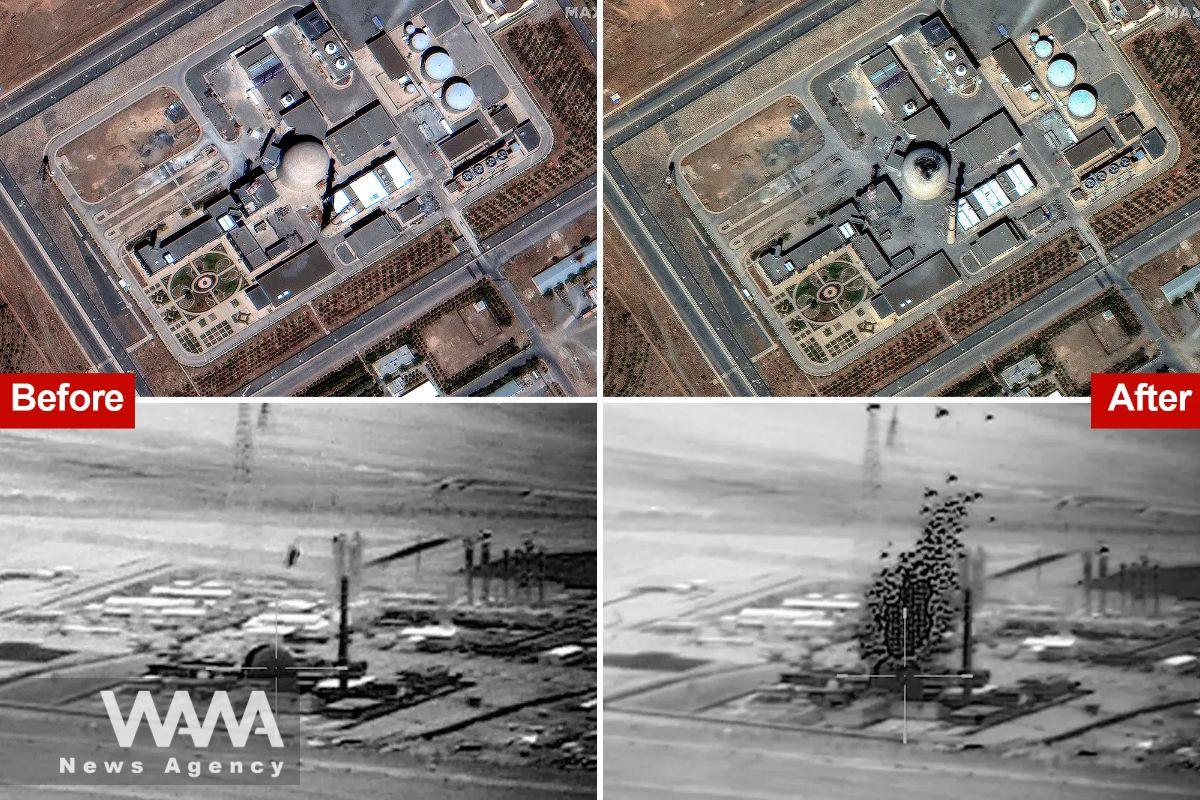

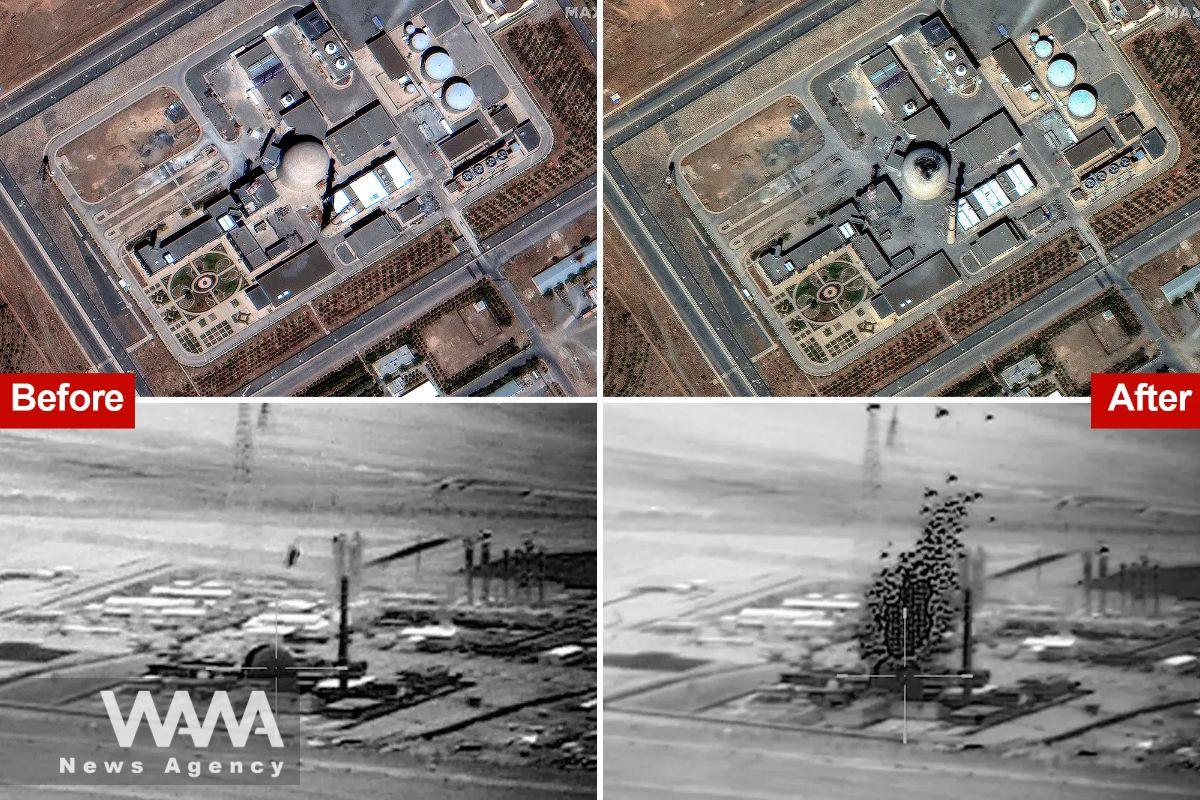

Arak nuclear facility after the U.S. strike. Social media/ WANA News Agency

2) Declaring readiness to negotiate: a message for domestic stabilization, not an actual invitation

For the past two months, senior Iranian officials have repeatedly stated that “Iran is always ready for negotiations.” But Araghchi offers a more precise framing: Iran is ready for real negotiations—not talks that begin with American preconditions.

This dual message is deliberately left ambiguous. Why? Because in the post-war environment, any hint of unwillingness to negotiate could:

unsettle Iran’s domestic markets,

increase Western diplomatic pressure, and

strengthen regional narratives against Iran.

Tehran therefore prefers to promote the following image: “Iran is ready; the U.S. is not.”

This framing works both domestically and internationally—assuring internal audiences while softening the psychological impact of the IAEA Board of Governors’ resolution.

WANA (Nov 21) – In an official statement, Iran’s Foreign Ministry described the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Board of Governors’ newly adopted resolution on the country’s nuclear program as “illegal, unjustified, and driven by political pressure,” stressing that the Agency has no authority to reinstate Security Council resolutions that have already been closed. […]

3) Araghchi’s trip to France: chemical weapons conference or political message management?

Despite claims that his visit signaled a revival of nuclear talks, Tehran insisted the purpose was the Conference on Chemical Weapons Prohibition. Yet European analysts see the significance elsewhere:

France is the only European actor openly worried about being excluded from the future of any nuclear agreement.

Paris knows that in a new Iran–U.S. deal, European oil, automotive, and technology sectors would likely be the first casualties.

Thus, in Paris—even without engaging in negotiation—Araghchi was managing a message: “Iran has not forgotten Europe, but Europe must also redefine its role.”

In other words, the trip was not a negotiation, but it filled the vacuum created by the absence of one—a vacuum Europe deeply fears.

WANA (Nov 27) – Seyed Abbas Araghchi, Iran’s Foreign Minister, who traveled to Paris at the official invitation of his French counterpart, held talks with Jean-Noël Barrot at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs. During the meeting, the two sides reviewed the latest state of bilateral relations between Tehran and Paris. Both ministers underlined […]

4) Saudi mediation: a constructed narrative convenient for regional media

Several regional outlets have recently promoted the idea of a “new Saudi role” in bringing Tehran and Washington closer. But Araghchi was explicit:

The implication is important: Iran wants the international audience to understand that the obstacle is not the lack of a mediator but U.S. behavior itself. This is precisely the point many Arab media narratives avoid.

As a result, the “Saudi mediation” storyline is useful for Riyadh, appealing for regional media—but inaccurate from Tehran’s perspective.

Iran’s President Sends Written Message to Saudi Crown Prince. Social Media / WANA News Agency

Tehran’s quiet shift: from field deterrence to diplomatic flexibility

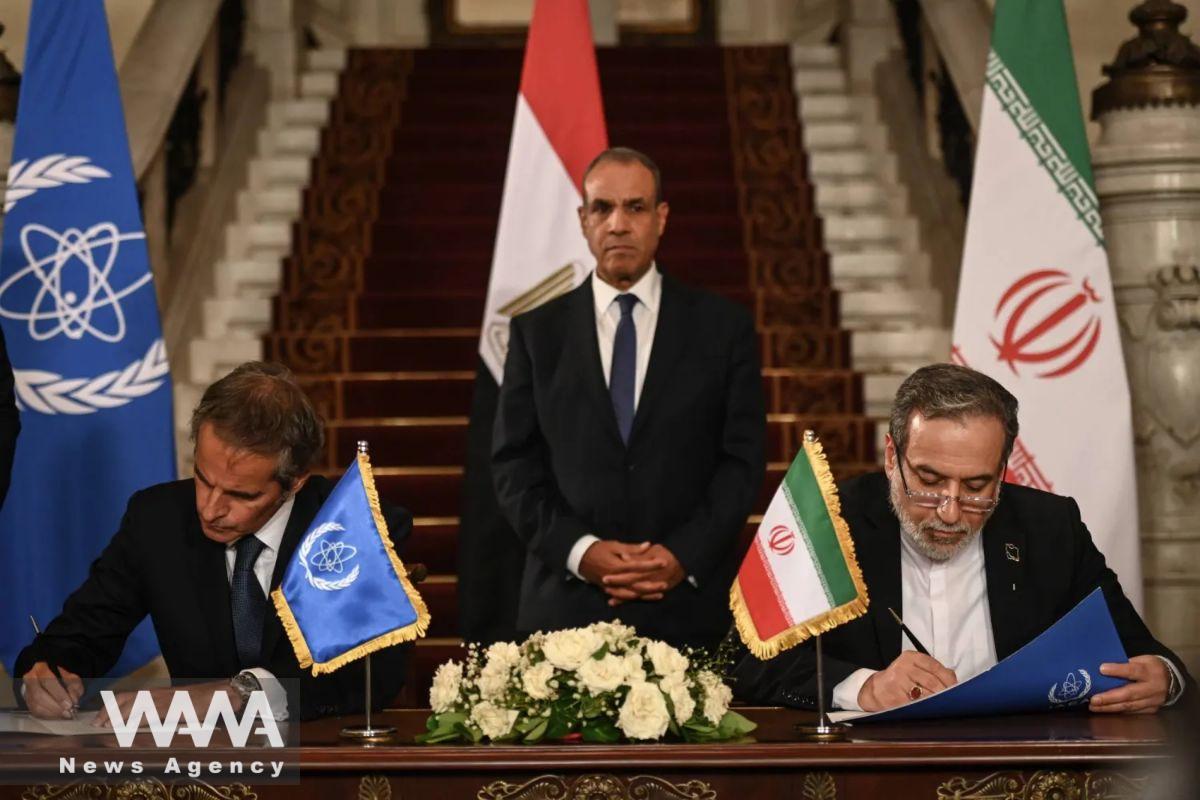

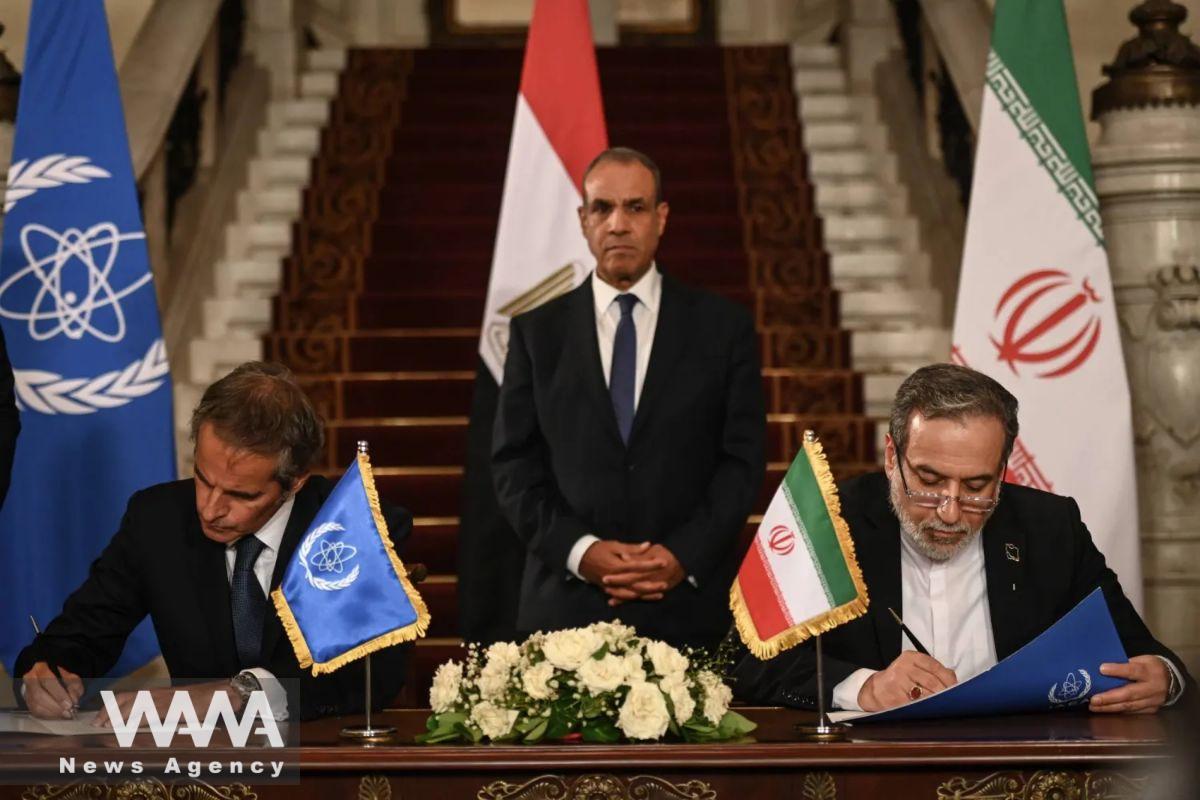

Araghchi reiterated several key positions: Iran continues enrichment at undamaged sites; access to bombed facilities is only possible under a new protocol; and the Cairo Agreement now forms the “framework for engagement with the IAEA,” replacing the Board of Governors’ resolution.

Iran has posed a fundamental question—one the international system cannot currently answer: “How can a bombed nuclear site be inspected using peacetime protocols?”

This is what distinguishes Iran’s 2025 nuclear policy from previous years: Tehran believes it is the IAEA that must adapt to new realities—not the other way around.

Cairo Agreement between Iran and IAEA. Social media/ WANA News Agency

Iran’s nuclear negotiations in 2025 resemble an empty field—one where everyone is still fighting

After reconstructing the official and media narratives, the broader picture becomes clear:

Iran says it is ready to negotiate—but not under fire.

The U.S. sees negotiations as necessary—but refuses to pay the cost of behavioral change.

Europe fears being sidelined.

Regional media fill the information vacuum with manufactured storylines.

Saudi Arabia has no mediating role—but a symbolic one.

And the IAEA faces a new crisis: “post-war inspections.”

In this environment, the main question is no longer whether nuclear talks will resume. The more important question is:

If future negotiations follow the same structure as before, what is the point of restarting them at all?

This is the challenge Iran is presenting to the world today—and one for which no one yet has an answer.