Ejide Mbarushimana would return to the Democratic Republic of the Congo in a heartbeat if he could.

It’s the place where he was born, where his family still lives and where every part of his identity is rooted.

But since fleeing to the United States in 2016, going back has never truly been an option. The ongoing conflict has made the region too dangerous, especially for members of the marginalized Tutsi community in the east, the Banyamulenge.

“I love being here in America, but I want to go back to my country,” Mbarushimana said, standing with members of the Congolese community who gathered in front of the New Hampshire State House Monday morning to demand justice for civilians killed in Congo. “But I can’t go back. Once I go there, it’s 50-50. There’s a chance of living, and there’s just a chance of being killed.”

Violence has persisted in Congo for more than 30 years. Three years ago, the conflict claimed the life of Mbarushimana’s uncle.

He and other advocates demanded that attacks on the Banyamulenge receive the same global attention as the wars between Israel and Palestine and between Russia and Ukraine.

Fisto Ndayishimiye speaks during the State House protest condemning the violence in his native Democratic Republic of Congo on Monday morning, December 1, 2025.

Fisto Ndayishimiye speaks during the State House protest condemning the violence in his native Democratic Republic of Congo on Monday morning, December 1, 2025.

Fisto Ndayishimiye, a Concord resident who fled Congo in 2016 after losing many family members to violence, said it was important for him to speak out for peace and for an end to what he describes as a genocide against the Tutsi community. He said he is advocating because he has simply had enough.

“We ask people to stand with us, to understand that I am not here because I wanted to be here. I’m here because I was asked to leave my own country,” said Ndayishimiye. “I’m tired of this, and I want people to show up and protest, too. The world needs to wake up.”

He echoed the same longing as Mbarushimana. If peace returned to his country, he would leave America in an instant. Back home, he owns land and cattle and would lead a life where he wouldn’t have to pay rent, as he does in Concord.

Decades-long conflict

Since the mid-1990s, Congo has endured relentless armed conflicts that have uprooted millions. These conflicts have involved fighting between the national army, rebel groups, like M23, and forces from neighboring countries such as Rwanda.

According to data from the United Nations, as of March, Congo has more than 7.8 million displaced people. Most live with host families in eastern regions, and 738,000 face “emergency” levels of hunger.

The roots of today’s conflicts stretch back to the 1994 Rwandan genocide, in which as many as one million people, mainly of the Tutsi ethnic group, were killed by Hutu extremists.

Mbarushimana, who works in Concord, said he talks to his relatives only once a month because of connectivity issues in his homeland. Every conversation brings the same grim reports: villages burned, livestock slaughtered, people murdered and communities starving.

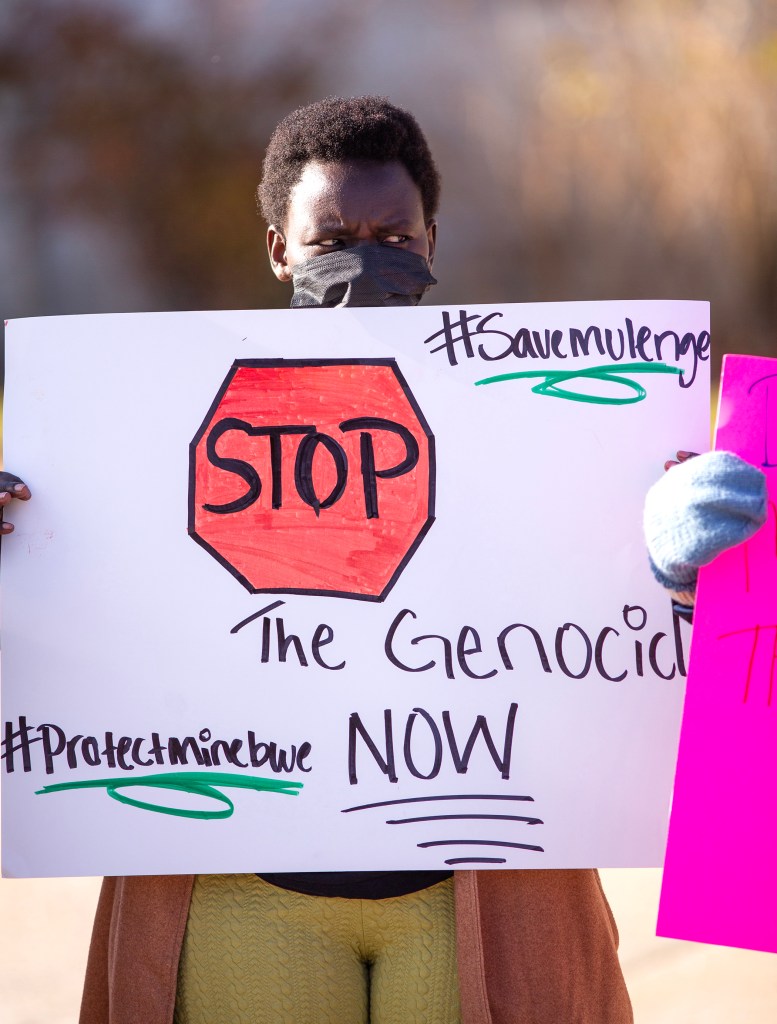

Chantal Mnkobua holds up a sign in front of the State House condeming the violence in her native Democratic Republic of the Congo on Monday, December 1, 2025.

Chantal Mnkobua holds up a sign in front of the State House condeming the violence in her native Democratic Republic of the Congo on Monday, December 1, 2025.

He said “losing livestock is equal to losing a worthy education, food and future” because when a family loses a cow or a goat, they lose income that they depend on. When the entire community loses half a million livestock, they lose their pathway to survival.

Clutching posters and waving Democratic Republic of Congo flags, the protesters asked the world to stand with them.

They said they were demanding justice, an end to the conflict and accountability for violence against the Tutsi community — the same global response other conflicts around the world have received.

They also urged the U.S. Congress to take action.

“Supporting Banyamulenge people is not about politics. It is about humanity,” said Ndayishimiye. “When you stand with us, we are sending a message, a message that every community, no matter how small, deserves justice.”