Nicholas Bloom, Philip Bunn, Paul Mizen, Pawel Smietanka, and Gregory Thwaites argue that there is evidence that Brexit has had a large and persistent negative impact on GDP, output and productivity in their new NBER working paper. You can read the paper in full here.

The UK is once again debating why its economy has grown so slowly since the mid‑2010s. Real wages have barely risen, investment has been weak, and productivity growth has disappointed. Many factors are at play – from the global financial crisis hangover to the Covid‑19 pandemic and the energy price shock following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – but one candidate has been central to the policy debate for nearly a decade: Brexit.

A large literature anticipated substantial long‑run costs of leaving the EU single market and customs union. Early ex‑post work using macroeconomic data also pointed to a sizeable hit to UK GDP and trade. Our contribution is to revisit the question now that almost a decade has passed since the referendum, bringing together ‘top-down’ macroeconomic data (like GDP and overall levels of employment and productivity) and ‘bottom up’ microeconomic evidence (on the output and employment of individual firms) in a single framework and comparing actual outcomes to the profession’s pre‑referendum forecasts.

In a new NBER working paper (Bloom et al. 2025), we combine data collected through the UK’s Decision Maker Panel (DMP), a survey of firms, with publicly available data to estimate the impact of Brexit. Our three main findings are:

Brexit has imposed a large and persistent cost on the UK economy. By 2025, we estimate that UK GDP per capita was 6–8% lower than it would have been without Brexit. Investment was 12–18% lower, employment 3–4% lower, and productivity 3–4% lower.

These losses emerged gradually. The impact was hard to see in 2017–18, but accumulated steadily over the subsequent decade as uncertainty persisted, trade barriers rose, and firms diverted resources away from productive activity.

Economists were roughly right on the magnitude of the impact, but wrong on the timing. The consensus pre‑referendum forecast of a 4% long‑run GDP loss turned out to be close to the actual loss after five years, but too optimistic about the longer run.

Measuring Brexit’s macro impact

Our first approach compares the UK’s post‑2016 performance with that of similar advanced economies; a similar approach to that used by John Springford in his earlier work. We use quarterly data for 33 advanced economies (the EU‑27, the US, Canada, Japan, Iceland, Norway and Switzerland) from 2006 to 2025, and examine GDP per capita, business investment, employment and labour productivity. Because there is no uniquely ‘correct’ way to weight the comparator countries, we consider five different approaches: a simple unweighted average, a GDP‑weighted average, a gravity‑weighted average (GDP divided by distance), a trade‑weighted average and a formal synthetic control. Our headline estimates take the simple average across these five methods, which draw similar conclusions irrespective of the weighting scheme, including when no weighting is used.

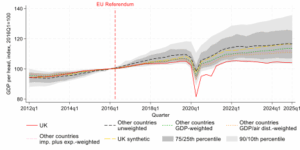

Figure 1 shows UK GDP per head from 2012 to 2025 compared to these five comparator aggregates. Before the referendum, UK GDP per capita grew at broadly the same pace as in the comparison group. After 2016, the lines diverge. By the year to 2025 Q1, UK GDP per head had grown 6–10 percentage points less than in comparable economies, and only about 4% in absolute terms over the whole period. Our central estimate – the average across the five weighting schemes – is that Brexit reduced UK GDP per head by around 8%.

Figure 1: GDP per capita cross-country comparison

We see similar patterns for other aggregates:

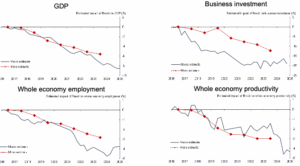

Business investment was particularly hard hit. The UK went from being a relatively strong performer pre‑referendum to a laggard afterwards. By 2025, business investment was 12-18% below the level implied by the comparator economies.

Employment has also underperformed, but to a lesser extent: we estimate a shortfall of around 4% relative to the counterfactual.

Labour productivity was around 4% below the comparator group by 2025.

The underlying assumption is that the UK would have performed as well as some kind of average of other countries in the absence of Brexit and this may not be true. Therefore, we complement the macro analysis with a micro‑econometric approach based on data from firms located in the UK.

Firm-level evidence from the Decision Maker Panel

Our firm-level evidence uses the Decision Maker Panel – a large monthly survey of UK firms. We construct a broad measure of EU exposure that averages across six dimensions: export share to the EU, import share from the EU, dependence on EU migrant workers, exposure to EU regulation, share of directors who are EU nationals, and EU ownership. These survey measures are matched to company accounts data.

This allows us to look at whether firms with higher EU exposure performed differently to other firms, both before and after the referendum. We find that firms with higher EU exposure grew faster than others before 2016. After the referendum, this pattern reversed, suggesting that Brexit did indeed have a negative impact on firms that were exposed to the EU, even after controlling for Covid-related shocks. We then scale our results up to the whole economy, and find:

Lower investment growth cumulating to a 12% shortfall in the level of business investment by 2023/24.

Lower employment growth around 0.5 percentage points lower per year, implying a 3–4% lower level of employment by 2023.

Total factor productivity (TFP) growth around 0.5 percentage points lower per year, leading to a 3–4% reduction to within‑firm TFP by 2023.

These estimates assume that unexposed firms were not affected by Brexit, when in fact they could have faced negative spillovers – for example through demand or supply chains – or positive spillovers, for example through the labour market, if unexposed firms found it easier to hire workers. This contrasts with the macroeconomic analysis, which should incorporate these impacts.

Importantly, the two approaches give similar estimates for the impact on GDP, investment, employment and productivity, although the macroeconomic estimates are typically somewhat larger (Figure 2). The fact that top-down estimates of the overall impact of Brexit on the UK economy as a whole, constructed by comparing us with other countries, broadly match bottom-up estimates, derived from estimating the impact on individual firms, is compelling evidence that Brexit has indeed had a large and persistent negative impact on GDP, output and productivity.

Figure 2: The estimated impact of Brexit

By Nicholas Bloom, Stanford University, Philip Bunn, Bank of England, Paul Mizen, King’s College London, Pawel Smietanka, Deutsche Bundesbank, and Gregory Thwaites, University of Nottingham and Resolution Foundation.