(Opinion) – A volunteer handed me a piece of paper. It said I was supposed to be a 15-year-old boy from Bolivia, fleeing gang violence.

My teenage son showed me his own identity card. He would pretend to be a 16-year-old Congolese boy, leaving his home due to war.

We walked outside into the dreary December Colorado afternoon to begin our one-hour refugee simulation hosted by Welcome COS. This year-old ministry has a vision to support refugees trying to resettle in Colorado Springs, educate the public and partner with churches.

We had one minute to choose just five pretend possessions. I picked pieces of paper that symbolized shoes, money, a cell phone, a passport and water. My son chose clothes, a cell phone, money, shoes and a motorbike.

Don’t forget your passport, I wanted to whisper to him but didn’t. For the next hour, I wasn’t supposed to be his mom. Besides, how did I know I’d made the right choices of what to grab before “fleeing?”

Your tax-deductible gift supports our mission of reporting the truth and restoring the church. Donate $50 or more to The Roys Report this month, and you can elect to receive “Gods of the Smoke Machine” by Scott Latta, click here.

Congregants attend an outdoor service at Eastbrook Church in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in Aug. 2021. (RNS photo by Bob Smietana)

Congregants attend an outdoor service at Eastbrook Church in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in Aug. 2021. (RNS photo by Bob Smietana)

I’m a journalist for The Roys Report (TRR), doing my best to expose abuses in the evangelical church. But I’m also a mom in the thick of raising my three teenagers, hopefully with hearts for justice. So, I’d jumped at the chance to bring my son to this event.

As rhetoric around immigrants and foreigners has heated up and public policy has turned against refugees, Christian refugee ministries are inviting believers to empathize. Baltimore-based World Relief and Exodus World Service from Chicago, have hosted these kinds of simulations in other cities as a way to build understanding. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has even created a video game with a similar purpose.

Last Saturday’s event was the first of its kind for Colorado Springs, said Amy Schulte, Welcome COS’s director and a trained counselor. About 100 people attended.

“The mission for this was to help people have just this little, tiny experience that broadens their understanding of why people flee and what they have to survive,” Schulte told me.

From trauma to safety

This city tucked against the Rockies has been the place of my own family’s resettlement of sorts. My husband and I were missionaries with Mission Aviation Fellowship in Indonesia for 14 years before we became whistleblowers and were forced to leave suddenly.

Our Asian-born kids spent most of their childhoods living in beautiful, tropical Borneo. They got to fly on small planes to visit ancient remote tribes, take boats to watch orangutans play, and practice their Indonesian language with our loving community.

But they also saw and experienced a lot of trauma. We lived with limited medical care, witnessing death and sicknesses, like tuberculosis and cholera. We had to evacuate our home due to uncontrollable fires and toxic smoke overtaking our region. The stress of trying to report safety and abuse concerns to our bosses also took its toll.

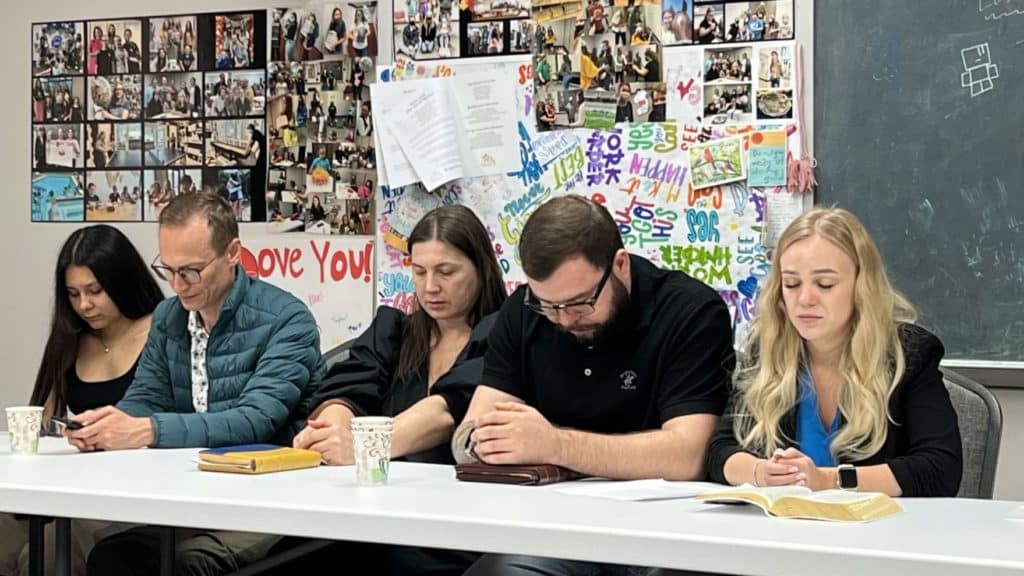

Refugees, including new Christian Aleksei Kozhevnikov and his wife, Milana, at far left, pray during a Russian-speaking Bible class at the Memorial church. (Photo: Bobby Ross Jr.)

Refugees, including new Christian Aleksei Kozhevnikov and his wife, Milana, at far left, pray during a Russian-speaking Bible class at the Memorial church. (Photo: Bobby Ross Jr.)

My kids had never lived in America before, so our sudden move here in 2019, with very few possessions, created a huge upheaval. My goal when we first moved to Colorado was to stabilize my kids and give them a chance to heal. This city has welcomed us well. I now spend most of my weekends driving kids to friends’ houses for birthday parties and movie nights.

But six years after our move to the United States, I’ve started to wonder if I need to protect them from a different snare: entitlement. With the ease of life in the American suburbs, had we lost our ability to notice needs? And could a refugee simulation help us so we could help others?

‘Driven from home’

Last week, with our few pretend possessions in hand, my son and I walked to the next station in the simulation: our first night on the run. Volunteers told us to find shelter. Our group of strangers huddled together under a single tarp, only to be approached by a “robber.”

A soft-spoken teenage girl told me to give her two of my possessions.

I’ve reported for TRR on Christian simulations-gone-wrong, such as Calvary Chapel’s boot camp, Patmos, which imitated torture in a way that traumatized students. So, before my son’s and my turn, I watched for signs of simulated violence with the group ahead of us. But the event was calm.

Schulte told me that was intentional for “Driven from Home,” the name of this event. Welcome COS believed families would want to do this together, so volunteers limited the realism of the simulation.

To the robber, I reluctantly turned over my pretend money and water. My son gave her his motorcycle and clothes. Next, we had to pay for passage on a raft with two of our remaining pretend possessions. I gave up my pretend cell phone and shoes and climbed into the rain-soaked raft.

A volunteer asked me to read aloud a real narrative of a refugee who had to choose between staying behind in war and taking her young kids on an overcrowded boat with no food or water. I could barely make it through the part where the mom tells her kids, “I’m so sorry,” without crying.

Schulte later explained it to me this way.

“These are real people who honestly never wanted to leave their country,” she said. “They fled because they had no other choice and it was the only way to keep their families and their own lives intact.”

Our next stop was a set of tents: the refugee camp. If we were lucky, each family would get one tent, one or two blankets and one bag of rice for the month, volunteers explained. But overcrowding meant multiple families might live in a tent and some people may not get food that month.

Our group crowded into a small tent that would be the school — likely with just one teacher for 50 kids, a volunteer explained. Another station for the refugees simulation was a clinic, which often has limited staffing and supplies. Some people live like this for decades, a volunteer told us. Other refugees die of disease.

Welcome House Raleigh rents a storage unit to help furnish homes for new refugees. This one in North Raleigh, N.C., is crammed full of household items. (RNS photo/Yonat Shimron)

Welcome House Raleigh rents a storage unit to help furnish homes for new refugees. This one in North Raleigh, N.C., is crammed full of household items. (RNS photo/Yonat Shimron)

Now was our turn to wait for a chance to cross the border into a more stable country. We all waited in line.

“Where’s your passport?” said the pretend border guard to the refugee in front of us. “You can’t pass without it.”

“Uh oh,” my son said, looking at his remaining possessions, none of which were a passport. “I’m cooked.”

I still had my passport; it was all I had left. Living as a guest in another country for 14 years has ingrained in me the need for identification papers. In that moment, I could no longer think like a 15-year-old Bolivian boy, but only as a mom. Though I knew in real life, passports are person-specific, I felt the impulse to give my paper that symbolized a passport to my son, even if it meant I’d stay behind. Are these the kinds of choices refugee parents have to make?

Even when refugees manage to be accepted into a country where they can safely live and work, they have an uphill battle of paying loans back to governments, the volunteers told us. They also have to learn another language, find a job, figure out how to get to the store and do all of this while recovering from the trauma of fleeing.

Logo for the refugee non-profit WelcomeCOS. (Photo courtesy welcomecos.org)

Logo for the refugee non-profit WelcomeCOS. (Photo courtesy welcomecos.org)

“We work with so many women who want so desperately to learn English but their trauma, the mental and physical impact of your trauma, just makes it so much harder to learn a new language,” Schulte told me later.

Our last stop was our debrief. What did we feel? What did we learn? What now?

“My hope … is for our churches to come back to what we’re called to be … welcoming spaces and places of safety,” Schulte told me. “I just want the church to be Jesus.”

On the way home, I felt unsettled by all we’d just learned. The needs are even greater than I’d realized. My son and I talked about what we could do. What if one of the kids in my son’s class had experienced this big painful story of leaving his home, but couldn’t even speak English?

My son didn’t hesitate. “I would become his friend.”

Rebecca Hopkins is a journalist based in Colorado

Rebecca Hopkins is a journalist based in Colorado