“Mission impossible,” Vice-Chairman of the US Federal Reserve Stanley Fisher told Ukraine’s central bank governor Valeria Hontareva in October 2014.

Fisher previously served as head of Israel’s central bank from 2005 to 2013, and helped “defuse financial crises for decades”, as New York Times called it. Yet for Ukraine a decade ago, he had no solution.

Follow our coverage of the war on the @Kyivpost_official.

Ukraine was torn apart by Russia’s annexation of Crimea, invasion of the eastern Donbas region, and a financial crisis worsened by former president Viktor Yanukovych’s corrupt rule. The currency plummeted and reserves were depleting. Ukraine’s newly formed armed forces needed billions the state didn’t have.

Most of the country’s 180 banks ignored supervision, forged balance sheets and pushed Ukraine’s economy to the verge of collapse. Hontareva then asked Fisher how to save the system but received no help.

Saving a broken system “turned out to be possible,” her former deputy, Kateryna Rozhkova, told Kyiv Post in October 2025.

Rozhkova would soon become the enforcer of Ukraine’s banking cleanup. Hired in 2015, she rebuilt supervision, shut down 90 insolvent banks, and confronted some of Ukraine’s most powerful tycoons amid threats to the National Bank of Ukraine (NBU) team.

Her decade inside the central bank reshaped her from a private-sector manager into one of the most recognizable, but also polarizing, ex-central bankers in Ukraine.

Other Topics of Interest

Quantum Systems, Frontline Robotics Launch Joint Drone Production in Germany

Germany’s Quantum Systems and Ukraine’s Frontline Robotics have launched a joint venture to mass-produce Ukrainian drones in Germany, with all systems destined for Ukraine’s Defense Forces.

The woman leading the cleanup carried a liability of her own. Before joining the NBU, she led Platinum Bank, the 22nd largest bank by assets in Ukraine in October 2016, owned indirectly by Odesa-based entrepreneur Borys Kaufman.

Kaufman was the 46th richest man in 2021 according to Forbes Ukraine’s rating, and is now the owner of Ukraine’s largest tobacco distributor Tedis Ukraine.

Years later, in 2024, Ukraine’s Supreme Court ruled that Rozhkova and 11 others bore joint civil liability for the insolvency of Platinum Bank in 2017. Rozhkova led the bank up to mid-2015 – the Supreme Court ordered them to pay Hr. 1.5 billion ($35.2 million) in damages.

Platinum collapsed in 2017. It would eventually return to threaten her career inside the very institution she helped rebuild.

But between 2014 and 2025, Ukraine’s banking system shrank from 180 to 60 banks thanks to the cleanup, which became known in Ukraine’s modern financial history as “the falling of the banks.” (“bankopad” in Ukrainian) Those that survived endured the 2014 invasion, COVID-19, Russia’s full-scale invasion and a wartime economy.

The change was led by the team at the NBU, which reinvented itself from a one-man show to a board where every voice mattered. It still receives praise from the International Monetary Fund and central banks around the world.

Rozhkova’s decade at the NBU ended on Aug. 15, 2025.

Kyiv Post begins a story in two parts of how Rozhkova, backed by the NBU’s reform team, helped end harmful practices in banks and reestablish authority. And how the shadow of Platinum continues to follow her.

This is Part I.

2014: The crisis that rewrote Ukraine’s financial history

In 2014, Ukraine’s economy suffered a deep recession, while real GDP fell by 15.8% in 2014-15. Ukraine and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) were busy negotiating macro financial packages.

But financial turmoil was not the only problem for Ukraine at the time. Ukrainians had just mourned more than 107 protesters killed by police violence in February 2014 amidst corrupt President Yanukovych’s regime. Reporters unveiled evidence of embezzlement on a grand scale.

Unmarked Russian troops had seized control of key sites across Crimea. In spring 2014, Russia invaded Ukraine’s Donbas, establishing puppet authorities in Donetsk and Luhansk. Thousands of citizens fled to more peaceful Ukrainian cities, never to return.

“No foreign currency, no liquidity, capital fleeing the country, clients in occupied territories unable or unwilling to pay. Export revenues collapsed, the hryvnia devalued, and banks’ balance sheets swelled as assets were revalued while collateral wasn’t,” Rozhkova told Kyiv Post.

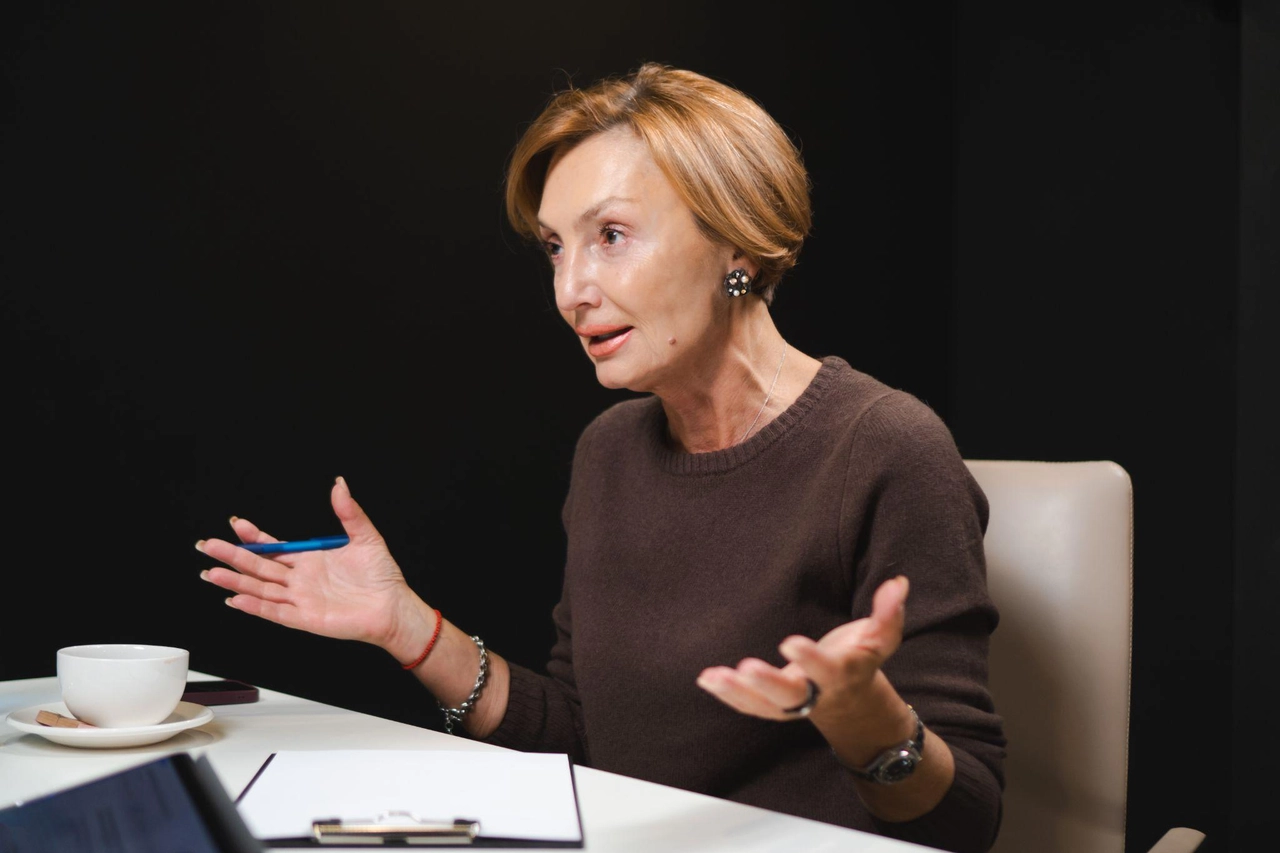

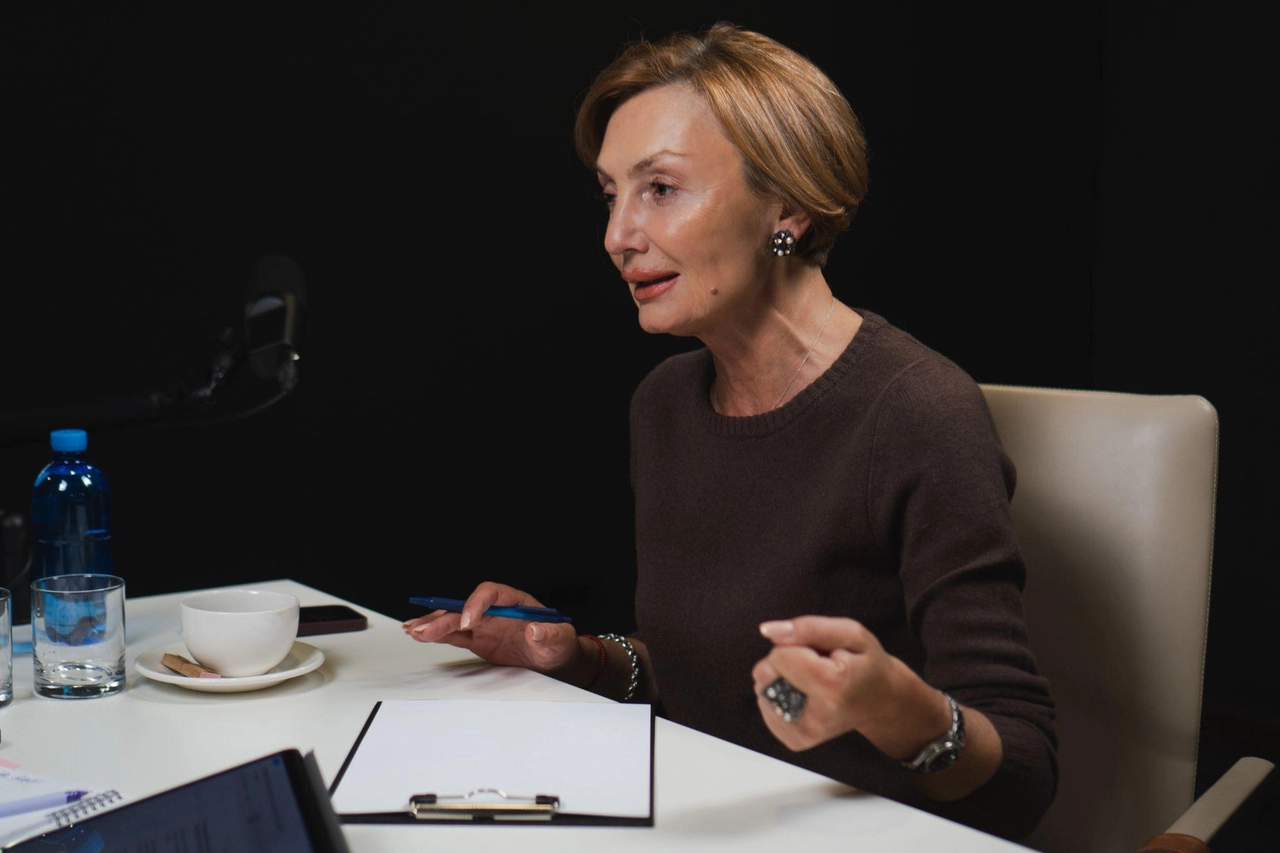

Kateryna Rozhkova, former first deputy governor of the National Bank of Ukraine, during an interview with Kyiv Post in October 2025. (Photo by Kyiv Post)

Kateryna Rozhkova, former first deputy governor of the National Bank of Ukraine, during an interview with Kyiv Post in October 2025. (Photo by Kyiv Post)

To avoid triggering martial law, which would have blocked IMF financing, the authorities legally framed Russia’s 2014 invasion as an “antiterrorist operation,” Rozhkova told Kyiv Post. That was the only way to access lifeline funds, and the IMF approved a two-year $17bn stand-by arrangement in 2014 and then a four-year $17.5bn Extended Fund Facility in 2015.

Private banks had almost no capital to withstand the shock – bailing them out was impossible for Ukraine’s almost empty budget.

Prior to 2014, banks in Ukraine were a part of a “gentleman’s set,” as Rozhkova calls it – “a bank, a yacht, a football club.” These banks served primarily as financial engines within oligarch business groups. “At that time, no one thought banks were obliged to have enough capital to withstand crises,” one source from the banking sector told Kyiv Post.

The uncertainty clearly frightened Ukrainians, as they withdrew 27% of deposits from the system (12% of Ukraine’s GDP) since the system’s peak figure, the IMF estimated back then. The inflation and devaluation accelerated as hryvnia cash flushed into the foreign currency markets.

“People needed clear communication, because even a small uptick in exchange rates at currency booths triggered public anxiety,”

Rozhkova recalled.

Kateryna Rozhkova, former first deputy governor of the National Bank of Ukraine, during an interview with Kyiv Post in October 2025. (Photo by Kyiv Post)

Kateryna Rozhkova, former first deputy governor of the National Bank of Ukraine, during an interview with Kyiv Post in October 2025. (Photo by Kyiv Post)

To steady the ship, following her appointment in 2014, then-NBU governor Hontareva began gathering bankers at the NBU for the first open roundtables in decades.

Rozhkova attended them as acting head of Platinum Bank. Her bank, just like other “problem” banks, lacked capital, had untransparent ownership and used “junk” securities as a collateral for borrowing.

The IMF did not want its billions to leak through holes in banking. So it demanded a diagnostic study of the whole banking system, sound asset quality, transparent ownership, recapitalization, and cutting insider loans. The NBU needed to install proper financial oversight, rebuild international reserves, set global standards and roll out inflation targeting.

The deadline? Four years. The alternative? Bankruptcy.

Supervision 2.0

By 2015, Rozhkova was busy recovering Platinum from potential insolvency, when her phone rang. “It was Pysaruk’s office,” she recalled.

Oleksandr Pysaruk worked as Hontareva’s deputy NBU governor, responsible for banking supervision, following his tenure as an ING Regional Head for Commercial Banking in Central and Eastern Europe. But he didn’t want another balance check.

Expecting further scrutiny, Rozhkova arrived at the NBU with piles of the latest statistics. Pysaruk, wearing his usual suit and rimless glasses, asked her to become the NBU’s banking supervision department head instead. Rozhkova remembered pausing, her eyes widening in surprise.

“You’re hiring me for supervision from a problem bank. Do you realize how that looks?” she recounts. “We’ll figure something out,” Pysaruk said.

She raised the same concern in her interview with Hontareva, who asked if anything still depended on her in that bank. It didn’t. “Then that’s that,” the NBU governor replied, agreeing to hire Rozhkova.

Ukrainian bankers were impressed. Hontareva had a plan on how to save the banks, Rozhkova recalled. In 2015, this drew Ukraine’s best economists to join the NBU and reform the system together. Her team also included long-serving NBU staff, and Rozhkova said she was able to reform the system without major staff changes.

Kateryna Rozhkova (second from left), Oleksandr Pysaruk (third from left) and then NBU Governor Valeria Hontareva (far right) during a meeting with bank executives at the National Bank of Ukraine in Kyiv, Nov. 11, 2015. (Photo by the NBU press service / Facebook)

Kateryna Rozhkova (second from left), Oleksandr Pysaruk (third from left) and then NBU Governor Valeria Hontareva (far right) during a meeting with bank executives at the National Bank of Ukraine in Kyiv, Nov. 11, 2015. (Photo by the NBU press service / Facebook)

Rozhkova revolutionized the banking supervision from a box-ticking formality to a real system. Before 2015, banks sent reports that declared everything was fine – and the NBU accepted them, discovering problems years too late.

Rozhkova introduced daily balance-sheet monitoring, early-warning indicators, and a system of “family doctors,” – supervisors responsible for communicating with banks. It was a reference to another major Ukrainian reform at that time – family healthcare, led by minister Uliana Suprun.

“They laughed at this idea, told me I’m nuts and that nobody will do it,” Rozhkova recalled, laughing. But NBU employees tried and it worked.

As she described the transformation of supervision, she sketched diagrams on a tablet to break down the complexity of bank balances and organization.

Kateryna Rozhkova, former first deputy governor of the National Bank of Ukraine, during an interview with Kyiv Post in October 2025. (Photo by Kyiv Post)

Kateryna Rozhkova, former first deputy governor of the National Bank of Ukraine, during an interview with Kyiv Post in October 2025. (Photo by Kyiv Post)

Her team grouped 180 banks into clusters based on business models and created a separate group of supervisory officers for each cluster. The leader of the group was constantly rotated to avoid tunnel vision.

Ten sources who worked with Rozhkova interviewed by Kyiv Post praised her energy and ability to move teams.

As one source who worked with Rozhkova told Kyiv Post under condition of anonymity: “Simply showing up and sitting in position was not an option. If suddenly there were no tasks, she would lose not only her sense of purpose at work, but almost her sense of existence.”

But not everyone liked Rozhkova. A second source told Kyiv Post that she surrounded herself with loyalists, regardless of their competence or ethics. Rozhkova oversaw dozens of working groups in different niches of the banking reform, and tended to have her favorites, according to the source. “Overseeing specialists from various teams, Rozhkova clearly divided people into ‘hers’ and ‘others’,” the source said.

Rozhkova downplays claims that people disliked her, saying disagreements were mostly about what they saw in the balance sheets. She recalls that some staff preferred the old supervisory approach that ignored fraud. As her colleague Denys Novikov told her: “Sometimes the National Bank could turn a blind eye,” but Rozhkova rejected such actions firmly.

Kateryna Rozhkova (right), former first deputy governor of the National Bank of Ukraine, during an interview with Kyiv Post in October 2025. (Photo by Kyiv Post)

Kateryna Rozhkova (right), former first deputy governor of the National Bank of Ukraine, during an interview with Kyiv Post in October 2025. (Photo by Kyiv Post)

Good or bad, Rozhkova relaunched banking supervision. Following diagnostics, the NBU revealed that Ukraine’s banking system had Hr. 66.6 billion ($2.8 billion) of losses in 2015, according to the NBU’s archive data. “It was frightening when we saw these numbers,” Rozhkova said.

The system had to be saved, but the oligarchs were looting what remained before the NBU was on their tail. Most Ukrainians, unaware of the backstage mechanics, blamed the NBU and the Deposit Guarantee Fund. Protests erupted at both institutions.

Ukraine’s central bank established new fair rules, but some bank owners did not want to comply with the new standards. The pressure also included threats, leaks and manipulations from PrivatBank and Bank Mykhailivskyi owners.

After the bank cleanup and NBU reforms were complete, a new governor tried to dismantle the system. Rozhkova stayed through all of this, but the Platinum bank decision was looming on the horizon.

To be continued in Part II.