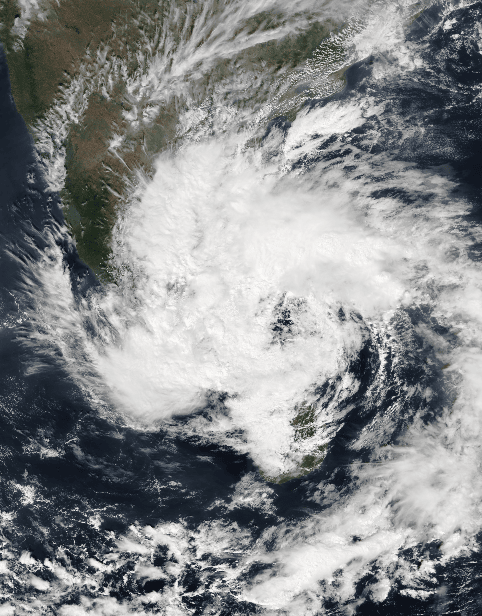

Cyclone Ditwah exposed Sri Lanka’s catastrophic lack of preparedness. After the first red alerts predicting very heavy rainfall were issued on the night of November 25, Sri Lankan President Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s public Facebook posts the following day focused on meetings with film producers and Road Development Authority engineers. It was only on the morning of November 27, as the rain intensified into a cyclonic storm, that he joined an emergency meeting on flooding and residents in the most affected areas were first alerted to the risk of heavy rain and strong winds. Cyclone Ditwah ultimately claimed over 600 lives with more than 180 missing, affecting 2.2 million people and requiring a United Nations estimated $35.3 million in emergency humanitarian assistance. President Dissanayake later acknowledged that Sri Lanka was unprepared to deal with the devastation caused by Cyclone Ditwah.

Sri Lanka’s delayed response was not abnormal but emblematic. The country consistently ranks among the top 10 nations at risk of extreme weather events in the Global Climate Risk Index, yet while it allocated $1.5 billion to military expansion in 2025, a 15% increase from 2023, it scrambled to find the UN-estimated $35.3 million needed for disaster response. This inverse relationship between spending and actual threat defines Sri Lanka’s deadly gamble: investing billions in weapons to fight yesterday’s wars while remaining unprepared for climate disasters killing hundreds annually. What is the point of Sri Lanka investing billions in a strong military if the country itself will be underwater because it failed to prioritize investment in climate change policies?

In their literature review within the Sri Lankan Journal of Economic Research pertaining to the evidence of climate change in Sri Lanka, Samaraweera et al. make it clear that the country’s climate vulnerability is not new as they cite major floods having occurred in 1907, 1913, 1940, 1947, 1957, 1967, 1968, 1978, 1989, 1992, 2003, and 2017. The pattern has intensified as climate change accelerates. The 2016 floods killed 104 people; the 2017 floods killed 213. Each disaster prompted governmental promises of reform that went unfunded, unimplemented, or abandoned when public attention moved elsewhere.

On paper, Sri Lanka possessed impressive climate policies and legal frameworks. Following the 2004 tsunami, Sri Lanka enacted the Disaster Management Act, No. 13 of 2005, establishing a comprehensive framework led by the National Council for Disaster Management with powers over policy, planning, coordination, and disaster response. Yet this system failed in practice: the Council did not convene as required and neglected its statutory duties of decision-making, oversight, and direction, undermining effective disaster management. Later frameworks also demonstrated unfulfilled intent: the 2010 National Policy on Disaster Management “aims for disaster management to take into account intersecting dimensions including climate change and the environment,” the 2012 National Climate Change Policy set goals to “develop strategies and mechanisms to prevent/mitigate and manage disasters caused by climate change,” and the 2014 National Disaster Management Plan promised to “mainstream disaster risk reduction” and link “climate change to disasters and adaptation measures.” These policies, while ambitious on paper, failed because they were never adequately resourced, enforced, or updated.

A Verité Research investigation found that between 2009 and 2018, approximately 1.98 million people were affected annually by floods, droughts, and landslides in Sri Lanka. Economic losses from disasters between 1998 and 2017 were estimated at 0.3% of GDP annually. As Ceylon Public Affairs concluded, “national disaster management systems, early warning mechanisms, infrastructure standards, and financial safety nets were largely designed for a climate that no longer exists,” assuming occasional extreme events rather than the near-annual disasters Sri Lanka now faces.

Cyclone Ditwah exposed not just infrastructure failure but systematic discrimination. Despite Tamil being a constitutionally protected official language, warnings came in Sinhala and English while Tamil, spoken by millions, was completely excluded.

Researcher Sanjana Hattotuwa’s analysis of the Disaster Management Centre (DMC)’s 68 Facebook posts between November 25-29 found just a dozen featured content in Tamil, with Tamil-speaking communities receiving zero landslide warnings even though they inhabited the hill country areas most vulnerable to landslides. The Meteorology Department showed similar failures. As the storm intensified into Cyclone Ditwa between the night of November 27 and the morning of November 28, detailed warnings in Sinhala were issued at multiple intervals, providing “specific coordinates,” movement speed, and intensification status. In contrast, the last Tamil-language warning was posted at 5:58 PM on November 27, meaning Tamil speakers received “zero updates during the critical 12-hour overnight window” as the cyclone rapidly intensified.

The Malaiyaha Tamil tea plantation workers, descendants of Tamil indentured laborers brought by British colonists over 200 years ago, bore particular devastation. Their colonial-era quarters of under 100 square feet, housing up to eight family members, were built on dangerous slopes while the tea plantations themselves on flatter ground remained unaffected, revealing what Colombo based climate researcher Melanie Gunathilaka described as “the amount of value placed on the lives of these people.” Kumaran Elumugam survived only because he was picking tea leaves when a landslide crushed his home, killing six family members.

Beyond plantations, farmers face collapse as they are buckling under climate pressure, spending up to 150,000 rupees per acre to cultivate paddy but receiving only 15,000 to 20,000 rupees in compensation when floods destroy their crops. The resulting mental health crisis has created rising numbers of widows as men take their own lives under repeated losses and mounting debt.

Rather than addressing these systemic failures, President Dissanayake declared a state of emergency on November 28, granting the military wide powers for arrest and detention while criminalizing not only misinformation but any content deemed “prejudicial” to public order, effectively suppressing criticism of disaster response failures. Meanwhile, Sri Lankan citizens mobilized community kitchens, donation drives, and flood-rescue databases because, as journalist Raisa Wickrematunge noted, “government agencies have, in the past, been slow to sound alarms and respond to crises.”

The Imperative for Comprehensive Policy Transformation

The path forward requires fundamental reordering of priorities away from military expansion toward climate survival. While Sri Lanka approved its National Climate Finance Strategy in September 2025, establishing 12 core financial instruments for climate action, Cyclone Ditwah exposed the critical gap between having frameworks and implementing urgent, lifesaving policies. As the strategy itself acknowledges, “public finance is not just about how much money is spent; it is about how it is used to unlock bigger flows of capital” and “will act as a lever, signal, and risk buffer to enable large-scale, sustained, and innovative financing for climate action.” The following policy recommendations represent minimum necessary interventions to prevent future disasters, building on existing frameworks while demanding immediate action where the government has catastrophically failed.

1) Defense Budget Reallocation to Capitalize Climate Finance Strategy

The National Climate Finance Strategy warns that “developing countries need between USD 130 billion and USD 415 billion annually by 2030” for adaptation, “yet only 5% of global climate finance was allocated to adaptation between 2021 to 2022.” Despite acknowledging that “unchecked climate change could slash global GDP by 7.6% by 2070” and that climate change “threatens agriculture, fisheries, and tourism, disrupting jobs and livelihoods” in Sri Lanka, the government allocated 442 billion rupees ($1.5 billion) to defense in 2025 while the Asian Development Bank estimated in 2019 that Sri Lanka’s housing, roads, and relief sectors lose $0.38 billion annually to climate catastrophes.

The government must establish a National Climate Resilience Fund and redirect at least 40% of the annual defense budget, approximately $600 million, to capitalize the strategy’s 12 financial instruments. This reallocation must be protected through legislation with constitutional amendments preventing political manipulation, recognizing that “public finance will act as a lever, signal, and risk buffer” and that the strategy requires “support from development partners, including risk guarantees, to enhance cost-effectiveness.”

2)Disaster Communication Equity Act

Sri Lanka must enact a Disaster Communication Equity Act establishing criminal penalties for government officials who fail to issue simultaneous trilingual warnings in Sinhala, Tamil, and English. The Official Languages Commission’s early December probe into the Disaster Management Centre identified it as a repeat offender, with chairman Nimal Ranawaka noting the DMC has a history of such lapses and has been audited in past years as well, demonstrating that voluntary compliance produces no change. The National Climate Finance Strategy makes no mention of linguistic equity or the systemic exclusion of Tamil-speaking communities from life-saving information.

Cyclone Ditwah demonstrated that voluntary compliance has repeatedly failed, with Tamil-speaking communities receiving no landslide warnings and no overnight updates during critical periods. All disaster agencies, including the Disaster Management Centre and Meteorology Department, must employ full-time trilingual staff with annual proficiency testing, and issue warnings within fifteen minutes across languages with identical content, including precise geographic coordinates, intensity, and evacuation instructions. The Official Languages Commission must have independent authority to impose sanctions for violations, and civil society must be empowered to seek judicial remedies. Compliance must be publicly verifiable through a database showing all warnings, timestamps, language, and content, ensuring measurable outcomes such as 100 percent trilingual coverage during declared disasters. The Disaster Communication Equity Act guarantees that early warning systems reach all communities equally, preventing language-based exclusion from life-saving information.

3)Emergency Plantation Worker Safety and Dignified Housing Act

Sri Lanka must enact an Emergency Plantation Worker Safety and Dignified Housing Act requiring all workers in landslide-prone areas to be relocated to safe housing within 24 months.

The geographic vulnerability of worker housing reveals deliberate disregard for their lives. Climate researcher Gunathilaka explained that the settlements were in much more dangerous areas than tea cultivation itself, noting the plantations, on flatter ground, were unaffected by the cyclone while the workers’ homes, which were closer to mountain slopes, were destroyed, demonstrating the amount of value placed on the lives of these people. While the strategy addresses “safeguarding critical sectors” and notes that “Sri Lanka’s agriculture sector employs a quarter of the working population” with vulnerability to “droughts, floods, and pest outbreaks,” it makes no mention of the plantation workers who face the most acute climate risks.

Under the Act, new housing must meet standards of 400 square feet per family with individual bathrooms, ending the practice where workers live in cramped, colonial-era quarters of under 100 square feet that often house up to eight family members with shared bathrooms or no sanitation at all. Housing must be located on geologically stable ground certified by independent engineers, with access to clean water, electricity, and waste management systems. The strategy’s emphasis on “ensuring long-term sustainability” and “improved livelihoods and community resilience” rings hollow when it excludes the most vulnerable workers from its protective mechanisms.

The Emergency Plantation Worker Safety and Dignified Housing Act must establish a Plantation Worker Climate Disaster Fund requiring tea companies to contribute 5% of export revenues. This fund will provide fair compensation during disasters and income support during evacuations, ending the current practice where workers are forced to return to estates to work because tea companies offer no support unless they do so, while evacuees are told to go back once weather clears despite unsafe conditions, leading to the simple plea that they need a home desperately. The strategy proposes “Public-Private Partnerships to drive investments in climate action” and states that “PPPs play a crucial role in developing climate-resilient infrastructure,” yet offers no mechanism to compel private plantation companies to protect their workers from climate disasters their business model helped create. Workers must receive full wages during evacuation periods with legal prohibition on retaliation for refusing unsafe work.

Companies must maintain emergency supplies and evacuation plans specific to each estate. Workers must have collective bargaining rights to negotiate safety standards and disaster protocols. Under the Emergency Plantation Worker Safety and Dignified Housing Act, companies failing to meet relocation deadlines must face export bans and seizure of assets for housing construction. Independent inspectors with surprise visit authority must verify compliance quarterly. The Act must grant workers direct legal standing to sue companies for violations without risk of termination.

4) Emergency Response System Restructuring

The Emergency Response System Restructuring must guarantee that local administrative offices remain operational during disasters and empower officials to procure essential supplies without fear of later scrutiny. During Cyclone Ditwah, residents seeking help found offices closed and officials hesitant to act. Every district must maintain emergency supplies for 10% of the population for 30 days, including food, water, medical supplies, temporary shelter materials, and essential equipment. The strategy notes that “some climate impacts are unavoidable, leading to Loss and Damage [L&D]” and that “L&D refers to the residual impacts from climate induced events which occur despite mitigation and adaptation efforts,” but provides no framework for immediate disaster response infrastructure. Supplies must be distributed across multiple secure locations to prevent single-point failures.

Evacuation centers must be constructed in all high-risk areas to international standards, providing sleeping arrangements, sanitation, medical services, and communication systems, with accessibility for persons with disabilities, children, and elderly members. A Unified Command System must integrate government agencies, military logistics, civil society, and international partners to coordinate rescue, resource distribution, and emergency planning. Community-level response teams must be trained in first aid, evacuation, and rescue. Civil society networks that proved effective during Cyclone Ditwah must receive formal recognition, funding, and inclusion in disaster simulations. Measurable outcomes include functional evacuation centers in all high-risk districts, verified stockpile levels, and response time metrics during simulations. Emergency Response System Restructuring ensures that institutional paralysis no longer impedes life-saving operations

5) Governance Reform and Anti-Corruption Measures

All disaster-related spending must be publicly tracked in real-time through accessible digital platforms. Independent audits must occur quarterly with results published within 30 days. The strategy emphasizes “robust governance and institutional coordination” as “critical elements for Sri Lanka to effectively channel climate finance” and calls for “enhancing transparency and tracking through mechanisms with clear monitoring systems to improve efficiency and accountability.” However, these commitments remain abstract without enforceable penalties for corruption in disaster spending, which must include mandatory prison sentences and full asset forfeiture.

Sri Lanka must prohibit states of emergency from granting military powers to arrest civilians for criticism of government response. On November 28, President Dissanayake issued regulations granting the military wide powers for arrest and detention, criminalizing critique of public services, and banning not only misinformation and disinformation but any content deemed prejudicial to public order, effectively allowing the military to suppress criticism of disaster response failures that had cost hundreds of lives. The strategy’s emphasis on “transparency and accountability” and “stakeholder engagement” becomes meaningless when emergency powers criminalize the very civil society participation it claims to promote.

Future emergency declarations must be narrowly tailored to genuine operational needs, subject to a process of judicial review which must be created in Sri Lanka, and time-limited with legislative oversight. Rather than criminalizing criticism, the government must partner with civil society organizations that demonstrated superior rapid response capabilities. The strategy’s stakeholder engagement framework identifies “NGOs, Civil Society Organizations, and advocacy groups” as “important for ensuring transparency, accountability, and inclusivity” and states they “represent vulnerable communities and often lead grassroots initiatives on climate adaptation and resilience,” yet provides no mechanism for integrating these organizations into official disaster response frameworks. Formal mechanisms should integrate community organizations with funding support for volunteer networks, community kitchens, and grassroots relief efforts. The poignant image of inmates at Welikada Prison donating their lunch rations to flood victims demonstrates the solidarity government should emulate.

Courts must have authority to review emergency measures, protect civil liberties during disasters, enforce climate policies against government resistance, and provide remedies for rights violations during emergency responses. Transparency and accountability must replace authoritarian emergency powers, ensuring that climate disasters strengthen rather than undermine democratic governance and human rights protections.

6) Constitutional Climate Rights and Enforcement

President Dissanayake has already pledged, using his party’s supermajority in Parliament, to introduce to Sri Lanka a new constitution. However, Sri Lanka’s new constitution must include an amendment which establishes climate security as a fundamental right. This includes rights to early warning in one’s native language, safe housing outside disaster-prone areas, fair compensation for climate losses, and government protection from climate disasters. While the strategy calls for “legal and regulatory frameworks” and emphasizes that “a National Climate Finance Strategy is an essential step towards mobilizing adequate funding,” it stops short of establishing enforceable constitutional rights. Citizens and civil society organizations must have standing to sue for enforcement of climate obligations, with courts empowered to mandate government action and allocate resources when constitutional rights are violated.

The strategy acknowledges the need for “strong policy support” and “clear project pipelines” but provides no mechanism for communities to hold the government accountable when these commitments fail. The constitution must prohibit backsliding on climate policies and spending commitments, with constitutional protection against reducing climate adaptation budgets below established minimums. These provisions would ensure that climate action cannot be reversed by future administrations and that vulnerable communities have legal recourse when the government fails to protect them from climate impacts.

7) Implementation Timeline and Monitoring

Within six months, Sri Lanka must establish the National Climate Resilience Fund, pass the Disaster Communication Equity Act with criminal penalties, create emergency procurement protocols, begin plantation worker housing assessments, and launch the governance reform initiatives. The strategy proposes a “short to medium-term: 1-3 years” timeline for various instruments but lacks enforcement mechanisms or accountability structures. Between six and eighteen months, the government must deploy upgraded coordination systems for emergency response, commence plantation worker relocations, build evacuation centers in highest-risk areas, and begin constitutional amendment processes for climate rights.

Between eighteen and thirty-six months, Sri Lanka must complete the majority of plantation worker relocations, achieve full trilingual capacity in all agencies, transform emergency response systems, establish comprehensive anti-corruption measures for disaster spending, and complete constitutional amendments establishing climate rights. An independent Climate Resilience Commission must publish quarterly progress reports, conduct annual climate vulnerability assessments, review and update policies based on latest climate science, and maintain public accountability through accessible reporting. The strategy mentions “monitoring and evaluation systems” and “publish regular updates to track progress” but provides no independent oversight body with enforcement authority.

The commission must have authority to compel government action when progress lags, investigate failures in disaster response, and recommend sanctions for officials who obstruct climate adaptation efforts. This monitoring framework ensures that implementation remains on track and that delays or failures are quickly identified and addressed, maintaining momentum toward comprehensive climate resilience.

The Choice Before Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka faces a choice between transformation and catastrophe. Each year of delay costs lives, destroys livelihoods, and deepens climate vulnerability. The policies outlined above represent not aspirational goals but minimum requirements for survival as climate impacts intensify.

The resources exist. They are currently invested in military expansion addressing no comparable threat. The technical knowledge exists. Early warning technology, climate-resilient construction, and fair compensation systems are proven solutions. The moral imperative exists, demonstrated by citizens who organized relief while their government expanded emergency powers to silence criticism.

What remains is political will. The 600 lives lost to Cyclone Ditwah demand more than mourning. They demand transformation. The Tamil-speaking communities who received no warnings in their language demand more than apologies. They demand enforceable equality. The plantation workers whose colonial-era quarters were buried in landslides demand more than sympathy. They demand dignified housing on safe ground. The farmers ending their lives under climate-driven debt demand more than compensation formulae. They demand economic security and mental health support.

As climate change accelerates, Sri Lanka’s window for adaptation narrows. The country can continue prioritizing military budgets over climate survival, Sinhala-only warnings over trilingual equity, and authoritarian emergency powers over genuine disaster preparedness. Or it can choose comprehensive policy transformation that treats climate security as the existential threat it is, requiring the same resources, urgency, and national commitment once reserved for military conflicts that pale in comparison to the climate crisis already claiming hundreds of lives annually. The choice is clear. The time to act is now.