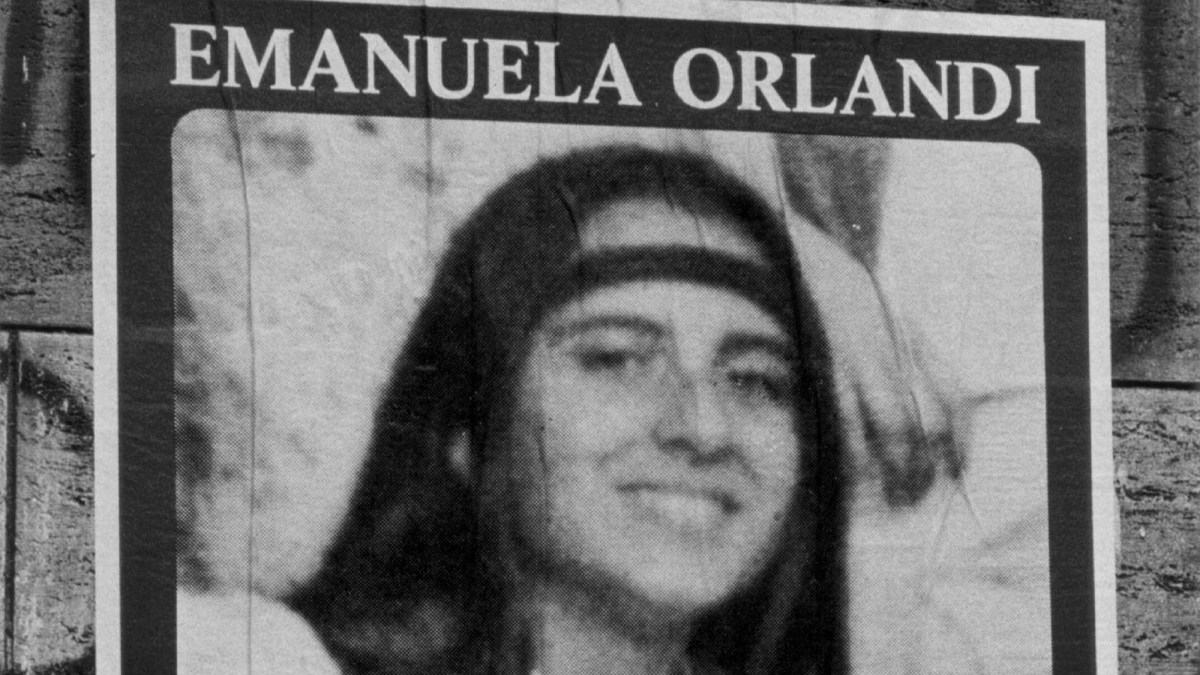

A childhood friend of a Vatican schoolgirl who disappeared mysteriously in Rome four decades ago has been placed under investigation for allegedly lying to prosecutors.

Laura Casagrande, 57, was a teenage contemporary of Emanuela Orlandi and may have been the last person to see her after they left a music lesson together in central Rome on June 22, 1983. Some days later she received a telephone call at home with a message calling for the release of Mehmet Ali Agca, the Turkish gunman imprisoned for shooting and wounding Pope John Paul II two years earlier.

The daughter of a Vatican employee and aged just 15 when she vanished, Orlandi has been seen over the years as a pawn to obtain Agca’s release, a possible victim of sex abuse in the Vatican and a lever with which to pressure the Vatican bank into repaying mafia funds diverted to support the Solidarity trade union in Cold War Poland.

• ‘Vatican Girl’ Emanuela Orlandi may have been pregnant while hidden in London

Following a 2022 Netflix documentary, Vatican Girl, both Italy and the Vatican reopened investigations into the case and a commission of inquiry was established by the Italian parliament.

Casagrande was one of the first witnesses to give evidence to the commission, apologising repeatedly for gaps in her memory over the crucial final minutes of Orlandi’s freedom.

Laura Sgrò, a lawyer for Orlandi’s family, welcomed the prosecutor’s initiative and said Casagrande had “made contradictory statements”. She added: “You can tell she is being reticent. Is she covering for someone? Why is there so much fear so many years later?”

Laura Casagrande giving testimony after her friend’s disappearance

CORRIERE DELLA SERA

Other schoolmates have turned out to be problematic witnesses, either because they were traumatised by Orlandi’s disappearance or had been intimidated in the intervening years.

Raffaella Monzi, a colleague at the music school, said she had been followed and threatened and is now a patient in a psychiatric clinic.

Pierluigi Magnesio, a contemporary at Orlandi’s high school, called a television crime show to admit: “If I talk they will kill me.”

“It’s shocking that after 42 years this climate should still exist. It’s terrible. We hope that if she [Casagrande] knows something she will finally get it out,” Sgrò said. “These people have come under tremendous pressure and we don’t know what is behind it.”

Andrea De Priamo, president of the parliamentary commission, said Casagrande gave two different descriptions of Orlandi’s departure from the school in depositions shortly after the event, but told the commission last year that she now had no recollection of her movements at all.

“My recollection of that day is that she didn’t come to choir practice. I was waiting for her because she was one of the girls that I was closest to,” Casagrande told the commission. “We didn’t leave together. I would have remembered that.”

Casagrande said she had suffered several nervous breakdowns in the course of her life and protected herself by excluding traumatic events from her memory.

Roberto Morassut, one of the commissioners, expressed frustration at her memory lapses, telling her: “I don’t believe that you didn’t fix the day of Emanuela’s disappearance in your memory. Although many years have passed, I believe it is an event that now belongs to the history of Italy.”

Shortly after his election to the pontificate in 2013 Pope Francis told Orlandi’s brother, Pietro, that “Emanuela was in heaven”, but he declined to provide any more details of what he knew about the case.

Pietro has called publicly for Casagrande not to be afraid and to come out with whatever she knows about the vital moments before his sister’s disappearance. His family hope Pope Leo, elected in May, may eventually prove more forthcoming than his predecessor on a mystery that continues to tarnish the reputation of the Holy See.