HOUSTON — I always get nostalgic when I come to Houston, the “Space City,” as I did for Saturday’s Texas Bowl between LSU and the Houston Cougars.

I loved space long before I loved sports. Before I had posters of LSU football greats like Bert Jones and Charles Alexander up in my bedroom, I had a plaque on my wall of Neil Armstrong and his immortal “One small step …” speech from when he walked on the moon in 1969.

Astronauts like Armstrong, Jim Lovell and Buzz Aldrin were my heroes as I watched moon missions (almost always with CBS’s Walter Cronkite providing the commentary), drank Tang and bounced around my house in pretend lunar gravity in a plastic astronaut helmet I wore one year for Halloween. I knew the names of all the astronauts by heart.

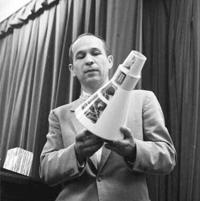

There was a name involved in the space race I didn’t learn until years later, an LSU grad who was integral to America’s first forays into the blue and along the way to the moon. His name was Maxime “Max” Faget (Fah-zhay).

Born in British Honduras (now Belize) in 1921, Faget graduated in 1943 from LSU in mechanical engineering, later receiving honorary doctorates from UL and the University of Pittsburgh. After LSU he became a submarine officer in World War II on the USS Guavina, serving for three years, partially because he was intrigued by the dynamics of how subs work.

“You had to volunteer to be on a submarine,” Faget’s son, Guy, told LSU in 2019. “They couldn’t just assign you to it. Dad chose a submarine because it behaves like a plane, except they’re in water.”

After the service, Faget got a job working for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), which in 1958 became NASA. Faget worked on rocket propulsion and later the X-15 project, a hypersonic craft that flew to the edge of outer space and was a forerunner of the spaceships to come.

Faget was right in the middle of designing those spaceships. In fact, he was the lead designer on the space capsule for Project Mercury, the one-man craft that sent the first six Americans like Alan Shepard and John Glenn into space from 1961-63.

From 1962-81, Faget served at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston as the space agency’s director of engineering and development, also having a hand in developing the two-man Gemini spacecraft that followed Mercury and the three-man Apollo command module that sent men to the moon from 1967-72. Even as the moon missions were going on, Faget was already at work helping design the space shuttle orbiter that would first take flight in 1981, the year he retired from NASA.

When Faget died in 2004, then NASA administrator and later LSU chancellor Sean O’Keefe paid him a significant compliment.

“Without Max’s designs and approach to problem solving, America’s space program would have had trouble getting off the ground,” O’Keefe said.

Faget never forgot his LSU roots. When he wasn’t designing spaceships or filing one of his dozen space-related patents, Faget was a devout LSU sports fan.

“He loved everything about LSU,” Guy Faget said.

Faget suffered a heart attack while watching LSU defeat Stanford in the 2000 College World Series final, but that didn’t stop him from asking his daughter Ann what the score was after arriving at the hospital.

“He didn’t want me to stay in the room with him,” she said. “I had to go out to the waiting room where the game was on and report back to him at the top and bottom of every inning.”

During a scene in the movie “Apollo 13,” an astronaut in mission control turns to a technician who helped solve a problem for the crew midflight, referring to him fondly as a “steely eyed missile man.” That moniker could have and probably should have been applied to Faget, who NASA flight director Chris Kraft referred to as “a true icon of the space program.

“There is no one in spaceflight history, in this or any other country, who has had a larger impact on man’s quest in space exploration,” Kraft said of Faget.

Without Faget, Armstrong’s one small step might not have taken place.