Approximately 3,000 years ago, a new type of building emerged in the land of Israel as a standard structure in sites across the region. Pottery too took on a remarkable level of uniformity at around the same time.

And pagan cultic sites that had stood for hundreds of years — even millennia in some cases — were destroyed and abandoned.

Any of these phenomena could be explained by a number of different scenarios, according to archaeologist Avraham Faust and biblical scholar Zev Farber. But the two say there is only one explanation that accounts for all of them together: the creation of a unified society under the strong hand of a single ruler.

In other words, a united monarchy of the type that the Bible says was adopted by the people of Israel and Judaea in the early Iron Age, led by Kings Saul, David, and Solomon.

“The Bible says that Israel decided to change their strategy and go for a king in the 10th century,” Farber, a senior editor at the Academic Torah Institute, told The Times of Israel. “Now, did they decide to appoint someone? Did somebody muscle their way in? That’s already a level of resolution we can’t answer.”

Get The Times of Israel’s Daily Edition

by email and never miss our top stories

By signing up, you agree to the terms

“The specifics are less relevant,” he added. “It does not have to be three [kings], maybe there were two, maybe five. However, the scaffolding that the Bible provides about the 10th century appears to align with the physical data from the 10th century.”

In “The Bible’s First Kings – Uncovering the Story of Saul, David, and Solomon,” published this year by Cambridge University Press, Farber, and Faust, a member of the Department of General History at Bar-Ilan University, describe the emergence of a thriving kingdom in the highlands of the southern Levant during the 10th century BCE.

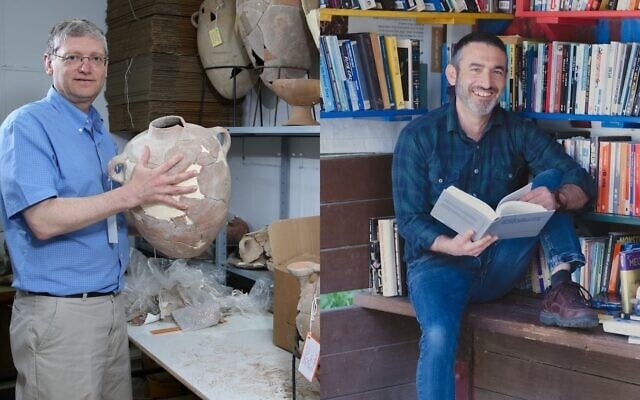

Left: Prof. Avraham Faust, an archaeologist and a member of the Department of General History at Bar-Ilan University. (Courtesy of Greg Solomon/Fulbright). Right: Dr. Zev Farber, a biblical scholar from the Hartman Institute of Jerusalem. (Courtesy of Tamar Hersko)

The book brings together archaeology, anthropology, and biblical scholarship to support the thesis that the kingdom did exist and that findings from the ground offer evidence for it — although not necessarily for the specific monarchs who led it. It processes “an enormous amount of data,” according to Faust.

With no direct first-hand evidence of the existence of a King David, his predecessor Saul, or inheritor Solomon, nor of the biblical account of their monarchic rule over an expanding kingdom from the Judaean hill country to Samaria and the Galilee, scholars have long questioned whether the biblically attested polity referred to today as the United Monarchy was ever a historical reality.

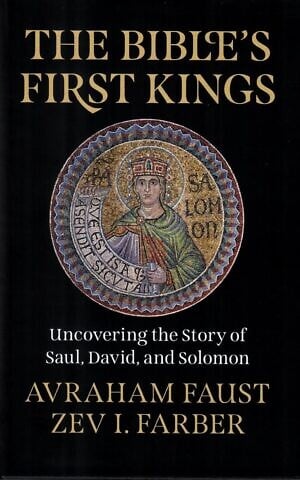

‘The Bible’s First Kings – Uncovering the Story of Saul, David, and Solomon,’ by Avraham Faust and Zev Farber, published by prestigious Cambridge University Press in 2025. (Courtesy, Avraham Faust).

In the 1990s, researchers reinterpreted monumental remains that had been traditionally dated to the relevant period as having come later, leading scholars to conclude that the powerful United Monarchy and its legendary sovereigns were likely foundational myths forged during the rule of later Israelite kings rather than rooted in historical fact.

Citing new discoveries and radiocarbon dating since then, Faust and Farber seek to put the idea of the monarchy back on its throne. The debate is far from settled, with academics continuing to argue over both the accuracy of dates and how to interpret various pieces of evidence.

One example is Khirbet Qeiyafa, a 3,000-year-old settlement some 25 kilometers (15.5 miles) southwest of Jerusalem that is considered by many one of the new discoveries that corroborates the existence of a kingdom in the area.

However, some archaeologists have questioned whether its 10th-century dating is indeed accurate (as radiocarbon can easily leave margins of error of decades) or if it was even an ancient Israelite site.

A longitudinal four-space (aka four-room) house at Atar Haro’a, the Negev Highlands. The structure became standardized in the 10th century BCE. The archaeological survey is carried out on behalf of the Zinman Institute of Archaeology, University of Haifa, and Bar-Ilan University. (Avraham Faust/Bar-Ilan University)

Noting that the scholarly debate has transcended the bounds of academia and drawn wide popular interest, Faust and Farber said they sought to make their book accessible and appealing to the general public, even if it is targeted to fellow academics.

“I hope readers will see that history is interesting, with new data and ideas continually emerging to shape our understanding of the past,” Faust said, sitting alongside Farber during a video interview. “More specifically, I believe the book demonstrates that the highland polity existed, and there is still much we can learn from the Bible.”

The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and brevity.

Times of Israel: What was your goal in writing this book?

Avraham Faust: Since the 1990s, the historicity of what is usually referred to as the United Monarchy, or the kingdom of David and Solomon, has been the subject of an ongoing heated debate. This book aims to integrate a vast amount of data and paint a broader picture of how we view the history behind the biblical story, drawing on archaeology, anthropology, and a critical reading of the biblical text. This bigger picture is composed of many smaller patterns or questions, and while sometimes there can be different answers to any single question, one of the strengths of our scenario is that all the answers to the specific questions fit into the broader picture, which is the emergence of a kingdom in the highlands [of the Land of Israel] and the expansion of this kingdom.

Zev Farber: What I love about the book is that it is not just about the question of whether there was a United Monarchy, and we show that the answer is yes. I believe the book uncovers what created Israel as a country. In the biblical text, we get a mythic story of Israel already as a fully formed people marching out of Egypt, doing miracles, and coming into [the land]. [In this narrative,] there is nothing so new about Saul, David, and Solomon. What we show, though, is that it was what happened in the highlands that really pushed the development of a national identity for self-protection. This period is not just a golden era in Israel’s history, but the formative period of a distinct type of identity.

From your perspective, what is the debate about the historicity of the United Monarchy?

Farber: If you look at the average biblical history book in the 1950s and 1960s, the general view was that the biblical story from Abraham was, to some degree, historical. In the 1970s, scholars began to argue that the patriarchs’ stories lacked a historical basis and to regard them as myths. Shortly after, the same happened to the Exodus, pointing to the lack of evidence of slavery in Egypt, and then it was [Joshua’s] conquest of Israel, even though the conquest had already been questioned in the past. The next big thing was the monarchy of Saul, David, and Solomon. Because once past that, there are archaeological anchors and sources that discuss the Israelites.

Faust: Until the 1990s, the vast majority of scholars assumed the existence of the United Monarchy in the 10th century BCE as a given. Then a small group of biblical scholars, known as “the revisionists,” started to question it. Many archaeologists initially dismissed this argument as not serious, but it sparked considerable debate. Later, the debate intensified as the concept of a new chronology, known as the “Low Chronology,” was introduced in archaeology.

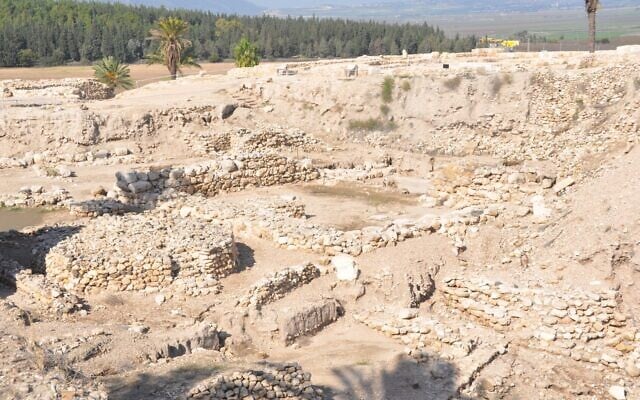

Excavations at Tel ‘Eton in southeastern Shephelah (Israel) in an undated picture. (Courtesy of the Tel ‘Eton Expedition)

Essentially, in the 1990s, some archaeologists suggested that major findings previously dated to the 10th century BCE should be redated to the 9th century. This included a destruction layer visible in many cities from around 1000 BCE, which had been associated with David, as well as fortified cities and palaces associated with Solomon. As a result, the proponents of the Low Chronology stated that there was no archaeological evidence consistent with the United Monarchy. Today’s discussions are largely a product of the Low Chronology debate.

At the same time, radiocarbon dating has at least partially offered some new answers to the question of dating, compared to previous methods such as pottery typology, which rely on interpretation.

Faust: The beginning of the Low Chronology was not focused on the United Monarchy but rather on the Philistines, as scholars noted that Philistine pottery commonly dated to the first half of the 12th century was missing from sites, like Lachish, which were believed to have been destroyed in the middle of the 12th century, or even in its second half. Their solution was to say that the Philistines only appeared at the end of the 12th century, and they started pushing the rest of the chronology down. Most scholars have not accepted the Low Chronology.

Prof. Avraham Faust from Bar-Ilan University surveys Iron Age sites in the Negev Highlands in 2025. The archaeological survey is carried out on behalf of the Zinman Institute of Archaeology, University of Haifa, and Bar-Ilan University. (Courtesy)

Since then, hundreds of radiocarbon samples have been dated, and most scholars think that the bottom line is a somewhat updated version of the original chronology. For example, the destruction traditionally associated with David did not occur in 1000 BCE, but in 980 or 970 BCE, which is still compatible with the United Monarchy, whereas the original Low Chronology was not. Some of the first proponents of the Low Chronology have partially walked it back.

How did Low Chronology influence biblical scholarship?

Farber: The Low Chronology has had a significant influence on many people, as most of us are not archaeologists, which leads to a fear of appearing naive. So, if the impression is that archaeology suggests there is no such thing as a Davidic or Solomonic kingdom, then we must accept that and work within the confines of that claim. For example, the book of Samuel, starting from [the narratives about] Saul, was considered a book that had a lot of reliable core information, in terms of the basic historical structure, and it was considered to have been [written] very early. Afterwards, scholars started to date it later, thinking that they could not argue with archaeologists. I think there is an inclination to err on the side of sounding skeptical.

Do you feel ideology or political and religious considerations influence the debate?

Faust: The humanities and social sciences are not exact sciences. In this sense, there are always biases. Some of them can be ideological or religious. Many of them are personal, which also exist in the hard sciences. The connection between archaeology and ideologies such as nationalism or imperialism has been known for many years. We all have biases. We should do everything possible to keep them at bay. As long as you’re very explicit about the data and the method of interpretation, you can overcome those differences or at least delineate the lines of disagreement. Most scholars will let the data dictate their interpretation. They might favor one interpretation over the other, but they wouldn’t intentionally ignore data.

A schematic map, showing the expansion of the highland polity, known as the ‘United Monarchy’ in the 10th century BCE. (Avraham Faust/Bar-Ilan University)

Farber: I think you do have a sliver of scholars who have a kind of fundamentalist view, always working to prove the Bible, or always trying to burn everything down, whether driven by extreme skepticism, political views, or anti-Israel sentiment. However, I think those are a fringe group with little influence, even if they sometimes get headlines because they say bold things.

You have mentioned that the book includes a massive amount of data. Can you elaborate?

Faust: We look at the transition between the Iron Age I [traditionally dated to ca. 1200-1000 BCE], the time before the monarchy, and the 10th century, and we point out many changes.

For example, there is a form of house that is very well known [in the Iron Age], the four-room house [a long house composed of four main spaces]. What we point out in the book is that in the Iron Age I, the classical form of the house is not yet established. A prototype of it appeared in limited regions, but in the 10th century, the classical, standardized form of the structure emerged, and it suddenly became widespread throughout the country. We believe this form [of house] was adopted by the highland polity. At Tel ‘Eton, a site I excavated and for which we have radiocarbon dates, in the early 10th century, someone leveled the top of the mound and built a 230-square-meter [2,475-square-foot] house, using high-quality building materials. We find the exact type of house in several sites in the Negev Highlands, as well as in Feynan [in modern Jordan], one of the copper production centers, and elsewhere.

Excavating a storage room with several smashed jugs at Tel ‘Eton in southeastern Shephelah (Israel) in an undated picture. (Courtesy of the Tel ‘Eton Expedition.)

Another change that we observe is the end of long-standing traditions in cultic areas, as the Israelite cultic traditions differed. For example, in Megiddo, on one part of the mound, a series of temples stood for millennia. The site was destroyed in the early 10th century, and when it was rebuilt, it was done for the first time without a temple. We see something similar in Tell Qasile [near the Yarkon River in central Israel], probably in Beth Shean, and more. As far as we know, during the Iron Age II, you have very few temples in Israel and Judah. When [the United Monarchy] expanded, it destroyed existing temples and did not rebuild them.

In addition, during the Iron Age I, there were a lot of local pottery traditions [across the land], in parallel to some types of pottery common everywhere in the region, like cooking pots. But all these local traditions disappeared in the 10th century. Something happened, and the bottom line is that you find a more unified type of pottery assemblage.

We consider [these changes] as the fingerprint of the expansion of the United monarchy.

The sacred area of Megiddo in northern Israel. (Avraham Faust/Bar-Ilan University)

Farber: When we talk about the Bible and history, obviously, there are certain things that can’t be studied. We cannot know whether Abraham had a conversation with a specific person, but the Bible offers a historical scaffolding that is subject to study. What we have begun to show is that even if we didn’t have the biblical story that said a kingdom was founded in the 10th century, thrived, and then was divided, the archaeological data is best explained by the idea that in the 10th century, a polity began. The scaffolding that the Bible provides regarding the 10th century appears to align with the physical data from that century.

Are there specific archaeological sites or areas that you looked at?

Faust: We look at many sites in the book.

One of them is Khirbet Qeiyafa [in the Elah Valley]. The site has been the subject of intense debate over the last 15 years. It is not strategically located because it is situated on a small hill, while nearby there are much higher hills, commanding larger areas, including the coastal plain. We think that the choice was intentional, as the Philistines were still strong at the time and [the Israelites] did not want to annoy them and force them to retaliate. But as we worked on it, we actually came to think that this was not the whole story.

According to the Bible, David, who posed a political threat to Saul, was moving around the Elah Valley area, even travelling from Adullam and Keilah in its upper part to Philistine Gath in its lower part. Therefore, by building a fortress there, Saul could actually not only encroach into the Shefelah [the Judean foothills in central Israel], which was officially controlled by the Philistines, his enemies, but also block groups like David’s from contacting the Philistines. When you look at Khirbet Qeiyafa in terms of the details of the story, the actual position makes lots of sense.

The site Khirbet Qeiyafa from the 10th century BCE, looking west toward the uninhabited (at this time) hill of Azeka, which blocks visibility toward the coastal plain. (Avraham Faust/Bar-Ilan University)

Farber: This helps solve a major problem for critical Bible scholars. If you don’t take the biblical narrative as historical, one of the things that people always wonder about is why, after Saul’s family is killed in a battle with the Philistines, David would not sell himself as Saul’s son-in-law, or [Saul’s son] Jonathan’s best friend, and instead the Bible preserves so many stories about Saul trying to kill him. From David’s PR perspective, the best thing for him was to highlight the connection with Saul. But [looking at Khirbet Qeiyafa], you realize that Saul wanting to kill David is actually the historical core of the story. The site is actually a physical example of Saul attempting to go south, as he chased David around, [consistent with] all the stories about it [in the Bible].

Is there another site that is significant to explain what happened in the 10th century?

Faust: The Sharon, or the central coastal line of Israel, is today the most densely populated part of the country; however, in antiquity, it was a marginal region due to its swamps and numerous environmental challenges. At certain periods, there were hardly any settlements, while at other times, there were more. In the Iron Age I, there were some settlements, and in the 10th century, they peaked, while later, during most of Iron Age II, they were almost non-existent. And the question is, why? This area is remote, and the only reason someone would invest in it would be for trade. In the 10th century, settlements flourished especially along the Yarkon River’s basin, at the southern edge of the Sharon.

Metzudat (fortress) Nahal Akrav in the the Negev Highlands. The archaeological survey is carried out on behalf of the Zinman Institute of Archaeology, University of Haifa and Bar-Ilan University. (Avraham Faust/Bar-Ilan University)

The only place that the Yarkon could serve as the contact point to the sea was a limited area that included Jerusalem, because for areas further south, there were Ashkelon and Gaza, and further north, there was Dor. In the 10th century, Jerusalem was the only serious candidate that could have benefited from this access to the coast. Later, after the kingdom was divided into Israel in the north and Judah in the south, the Yarkon remained under the control of the northern kingdom, which did not need it to access the sea, while Judah [and its capital Jerusalem] couldn’t use it, so the sites declined.

Interestingly, the Sharon is mentioned in the Bible only in a few lists, and all of them, even though they were probably written later, refer to the time of David and Solomon, therefore, the 10th century, when the region flourished.

Is the book your final word on the United Monarchy, or is there more research to do on the topic?

Faust: In archaeology, we have new data all the time, and anytime something new is excavated, we always try to see whether and how it fits in. If the book had been written today, it would have included additional elements, for example, new and interesting studies in the Negev, whose results are very relevant for our analysis. The work does not end here.