This year marked the 100th anniversary of Portugal’s biggest financial scandal that almost broke the Bank of Portugal. Just how did small-time con man Artur Alves dos Reis pull off an audacious banknote forgery and almost get away with it?

Text: Chris Graeme; Photos: Bank of Portugal & Supplied

The Bank of Portugal. Just the mere mention of the name these days conjures an image of a fortress of stability, financial prudence, watchful regulation and sound money management.

And that is by no small measure down to the responsible stewardship of the bank’s last governor Mário Centeno, who left his post after five years in July, widely seen as probably the best governor in 20 years.

But turn the clock back a century and things at the Bank of Portugal were very different under the stewardship of António Eduardo Ferreira de Sousa, when the bank was unwittingly subject to the biggest bank note forgery in history.

The times were anything but stable. Portugal had been subject to years of corruption, economic and political instability, and high inflation and unemployment.

In a game of revolving doors, between 1910 and 1925, no less than nine presidents and 45 ministers came and went amid a climate of extreme instability and civil unrest marked by 25 uprisings and 325 bomb incidents resulting in three dictatorships.

The scene was set for Artur Alves dos Reis to make his grand entrance and pull off the scam of the century.

Artur Alves dos Reis hoodwinked the Bank of Portugal and the British firm Waterlows that printed banknotes for the Bank of England.

The stage is set

Charming, dapper and debonair, Artur Alves dos Reis was already a seasoned criminal having been imprisoned for embezzlement in 1924. The trickster had audaciously gained control of Ambanca, a stock market listed Angolan rail company with considerable cash reserves of US$100,000.

Alves do Reis had done this by acquiring shares using post-dated cheques drawn on a New York bank. Once he had gained control, he used company funds to meet the cheques. He got caught and spent 54 days behind bars in Lisbon.

Returning to Angola, he met a small-time petty crook called José Bandeira, who was seeking business on behalf of a Dutch investor. Bandeira introduced him to three equally shady characters who would end up being his co-conspirators in a much more audacious forgery plot.

These men were António Bandeira, José’s brother and a Portuguese official in the Netherlands, Adolf Hennies, a German war profiteer and spy whose actual name was Johann Adolf Doring, and Karel Marang van Ysselveere, a Dutch businessman of murky dealings.

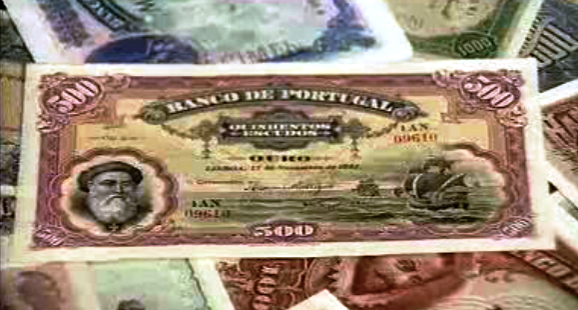

The 500 Escudos banknote that Alves dos Reis successfully forged – the equivalent of €500 today.

Sights set on the Bank of Portugal

In the Roaring ‘20s, which in Portugal was exploding with civil strife rather than roaring, Portugal’s central bank was privately run and responsible for issuing the country’s banknotes.

More importantly, as a listed entity, the Bank of Portugal had shares that could be traded on the open market, leaving it open to a takeover since the government had a minority share.

But the bank’s banknotes were not manufactured and printed in Portugal; the contract was outsourced to a reputable English company, Waterlow & Sons.

Alves dos Reis cleverly worked out that the bank’s bookkeeping left a lot to be desired (something that would never have happened under the watch of Mário Centeno).

He also discovered that the bank’s registers were incomplete and that, while it had the exclusive right to issue banknotes on mainland Portugal, this did not cover the country’s colony Angola.

Alves dos Reis set up a false contract in which the State of Angola authorised him to arrange a loan of £1 million (100 million escudos) in exchange for the right to issue a similar amount of Portuguese banknotes in Angola.

In fact, this was completely illegal, since the Banco Ultramarino had the exclusive right to issue all banknotes for use in Portugal’s colonies.

Nevertheless, he got the contract notarised and authenticated by the consulates of France, Germany and Britain.

Pic: Flush with money, Alves dos Reis bought luxury cars like this one

The English printers that were duped

Now all he had to do was find a firm that could exactly replicate existing Bank of Portugal notes in circulation for supposed use overseas, get the notes delivered to himself, acquire a majority of the central bank’s shares using the false notes, and live off the proceeds of his ill-gotten gains.

The specific notes Alves dos Reis had in mind were the 500 and 1000 escudo notes, known as the poets’ notes since they featured Luís de Camões and João de Deus Ramos.

Alves dos Reis’ co-conspirator Karel Marang van Ysselveere went to London in December 2024, armed with the certified contract for a meeting with the printers Waterlows pretending he was an accredited representative of the Portuguese government, introducing himself as the Honorary Consul-General of Persia to The Hague.

Meeting Sir William Waterlow, the company’s chairman, Marang told him he represented a Dutch syndicate intending to invest in Angola, and that their contract required them to issue Bank of Portugal notes identical to the notes already in use in Portugal and convinced him that the notes would be overprinted with the word ‘Angola’ after delivery.

Incredibly, for such a seasoned businessman, Sir William did not smell a rat, despite there being no direct authorisation from the Bank of Portugal, and made no simple due diligence checks with the bank or any Portuguese government official before agreeing to print the notes.

Instead, he trusted a false set of documents, all notarised, including contracts between Alves dos Reis and the government and between the Bank of Portugal and the government of Angola authorising the printing of 200,000 500 escudo notes.

A forged letter from the Bank of Portugal was eventually produced, and Sir William had all the documents duly translated and notarised by a London notary and the printing contract was signed for a fee of £1,500.

In an even more bizarre twist, Sir William sent a letter to the Bank of Portugal confirming the reception of the order, which went unanswered.

Another forged letter gave instructions on the numbering of the notes and which signatures were to be used.

Prior to this, Alves dos Reis had expertly worked out that 90,000 of the 200,000 notes could have numbers that did not correspond to any notes already in circulation.

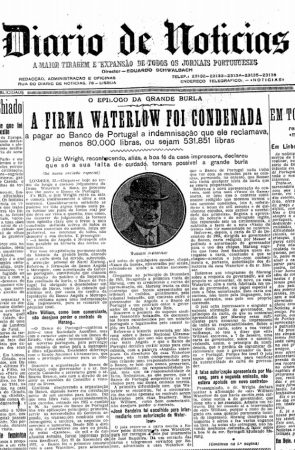

The lead story in Diario de Noticias which details the scandal of the printers Waterlow which failed to adequately check with the Bank of Portugal as to the veracity of the order.

The false notes enter circulation

The first notes were delivered on February 10, 1925, arriving in Lisbon as diplomatic baggage. Alves dos Reis paid out some bribes and then hired middlemen to open multiple bank accounts in Lisbon and Porto and buy foreign currency on the black market.

There were rumours that false notes were circulating, but with the bank seeing no evidence of this, the rumours were quickly scotched.

And although Alves dos Reis had managed to work out the sequence of bank governor names and serial numbers used by the Portuguese central bank, he had neglected to eliminate numbers already ordered.

When Waterlow realised that some bills had the same numbers as others they had previously printed, they alerted the “bank” (actually, they alerted Alves dos Reis).

Nevertheless, the Bank of Portugal was forced to issue a statement reassuring the public that the notes in circulation had not been forged.

Alves dos Reis even went as far as to experiment with inks and chemicals in an attempt to make the banknotes well circulated using camphor, water and lemon juice.

Living the high life

Now a wealthy man, Alves do Reis began a spending spree, living a playboy lifestyle, buying expensive jewellery for his wife, flash cars and a lovely Lisbon mansion called ‘The Palace of the Golden Boy’ (Palácio do Menino de Ouro) which, interestingly enough, is now occupied by the British Council.

In April 1925, the master forger set his sights on founding a bank in Angola, Banco Angola e Metropole (BAM) with a plan to use it to invest in Portuguese and Angolan companies, although his main ambition remained buying a controlling share in the Bank of Portugal.

Alves do Reis put José Bandeira in charge of the new Angolan bank, and by illegally increasing the monetary base and investing heavily in currency, land, building and businesses, he and Bandeira created a boom in the Portuguese economy.

In late 1925, Reis and the other co-conspirator Adolf Hennies made a tour of Angola, buying properties, investing in corporations and making development plans. He was hailed there as a saviour and as “Portugal’s own Cecil Rhodes”.

Buying a share in the Bank of Portugal

One way of controlling the narrative and never getting caught depended on Alves dos Reis buying a controlling share in the Bank of Portugal.

With control of the bank, the entire counterfeiting could be swept under the rug, ensuring that there would never be any evidence of the fraud.

While still in Angola, he ordered the other two conspirators to find out who owned shares and buy them up, eventually controlling 10,000 of the 45,000 shares needed for a controlling interest in the central bank.

Discovery and arrest

Things began to unravel for Alves dos Reis when a Porto moneychanger became suspicious that all the new notes were not in numerical order and that his employers (no doubt bribed beforehand) were destroying the related paperwork.

He alerted the Bank of Portugal which contacted the police. A team at the Bank of Portugal led by the governor himself spent December 5 and 6 checking the new notes and discovered four pairs of duplicated notes.

BAM managers and staff were quizzed and arrested and the new bank’s operations were suspended.

Alves dos Reis, who was en-route from Angola to Portugal, was arrested in Lisbon on arrival while the Bank of Portugal held an emergency board meeting and decided to withdraw and redeem all of the Vasco da Gama notes in circulation.

On the Monday, the bank issued a redemption notice with a deadline for December 16, while Waterlows of London was summoned to the bank to assist it in separating good notes from the bad. There were long queues outside the bank.

By December 16, the terrifying scale of the problem was evident. They had redeemed 715,577 notes – 115,577 more than the bank had actually issued in genuine notes.

The result was that even the Bank of Portugal governor and his deputy were arrested, although they were quickly released.

In the trial that followed, Reis’s forged documents and widespread cynicism about the nation’s elites were convincing enough for judges to suspect that Bank of Portugal officials and others in the government and establishment might really have been involved.

This delayed the sentence for five years pending further investigations, but Reis was finally tried in May 1930. He was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

In prison, Reis converted to Protestantism and converted other prisoners. He was released in May 1945, and ironically was offered, but refused, a job as a bank employee. Reis died of a heart attack in 1955.

Artur Alves do Reis was a symptom of the widespread corruption and instability that existed in Portugal at the time, and the lack of confidence among the general public in its governing figures and institutions ultimately led to an unassuming Coimbra economist, António Oliveira de Salazar, to put the country’s accounts on an even keel.

Unfortunately, using a national emergency as a pretext, Salazar installed a dictatorship that lasted until April 25, 1974. It is interesting to reflect that the Alves dos Reis case, while not a direct cause of the suspension of democracy in Portugal, was one of the many factors that undoubtedly was used to justify its necessity.