Building upon the methodological framework outlined above, this phase applies archaeoengineering principles to the structural examination of the Holy Crown of Hungary. Technical observations are integrated with art-historical interpretation and archaeometric data to establish a scientific basis for determining the Crown’s material composition, origin, and period of manufacture. Elements of this investigation have been discussed in earlier publications by the author; relevant findings are referenced where appropriate. Newly obtained interdisciplinary results and methodological refinements are presented in detail in the following sections.

Earlier engineering research concentrated on validating technological observations to minimise error and ensure reproducibility. The present analysis advances this work by demonstrating, through the Holy Crown case study, how a coherent archaeoengineering approach can generate verifiable evidence and deepen understanding of both the object’s construction and its historical context.

Visual investigation, CAD modelling, and digital documentation

A detailed visual assessment of both the cross-strap and the hoop crown was previously published in peer-reviewed engineering studies, notably Investigation of the Holy Crown as a Metal Structure30,31. In the present analysis, direct inspection was combined with three-dimensional modelling for engineering evaluation. Within the broader archaeoengineering framework, however, these stages are conceptually distinct: visual observation constitutes the indispensable point of departure, while CAD modelling provides a key interpretative extension. Alternative workflows may apply when an accurate digital model already exists.

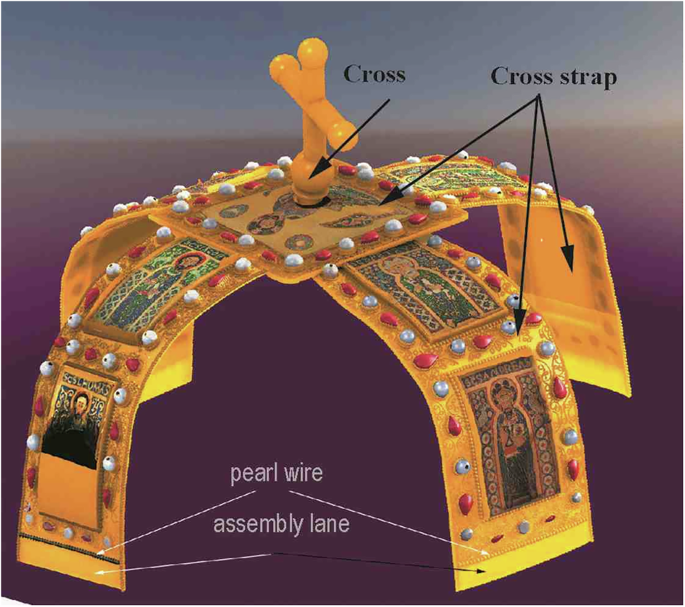

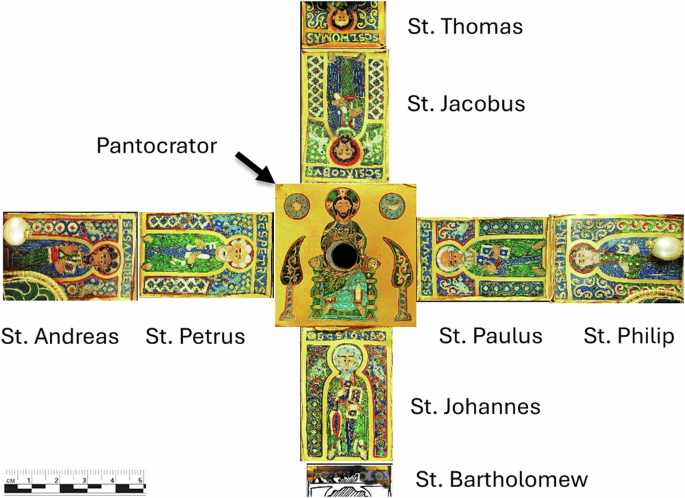

Figure 2 depicts the cross-strap, Fig. 3 the arrangement of the enamel plaques (scale 1:2), and Supplementary Fig. S1 the plaques at full scale (1:1). Several new observations refine earlier interpretations. The dense ornamentation and overall geometry of the cross-strap form a closed composition, indicating reliance on a supporting structural base. The continuous beaded wire encircling the roof plate—and repeated along the cross-strap arms—indicates deliberate design correspondence between these elements.

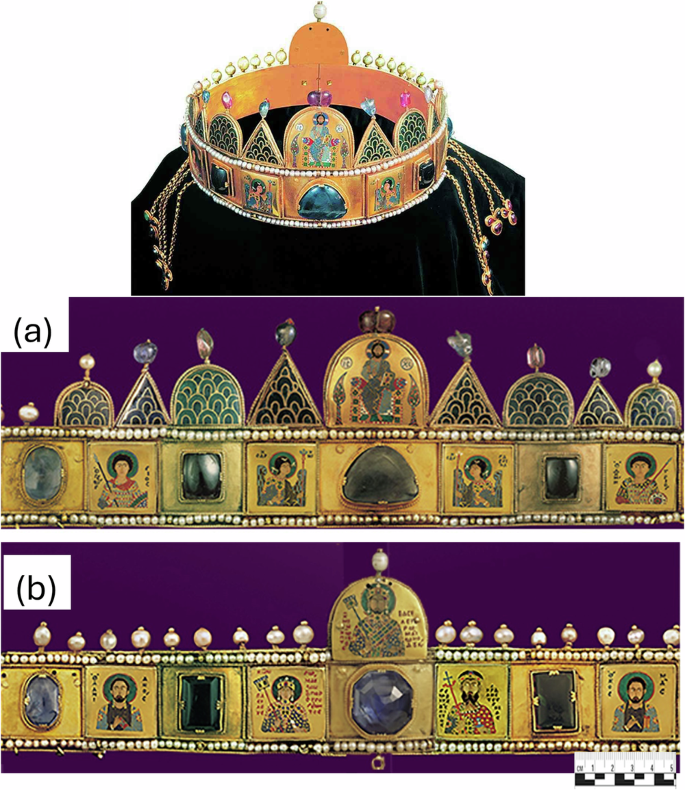

The hoop crown (Fig. 4) comprises eight segments, each housing a gemstone and an enamel plaque (Fig. 4a and b). The broader front and rear panels suggest deliberate preparation for integration with the cross-strap. This division yields symmetrical halves defined by the axes of the wider gem fields, yet the diadem, pendilia, and other ornaments are offset to align precisely with the cross-strap arms.

The proportions of the cross-strap and hoop crown were purposefully coordinated. Mounting a four-armed, domed cross-strap is feasible only on an eight-part circlet, each section combining an enamel plaque mount and a gemstone field. The circlet’s diameter and the cross-strap span are thus interdependent parameters of a unified design.

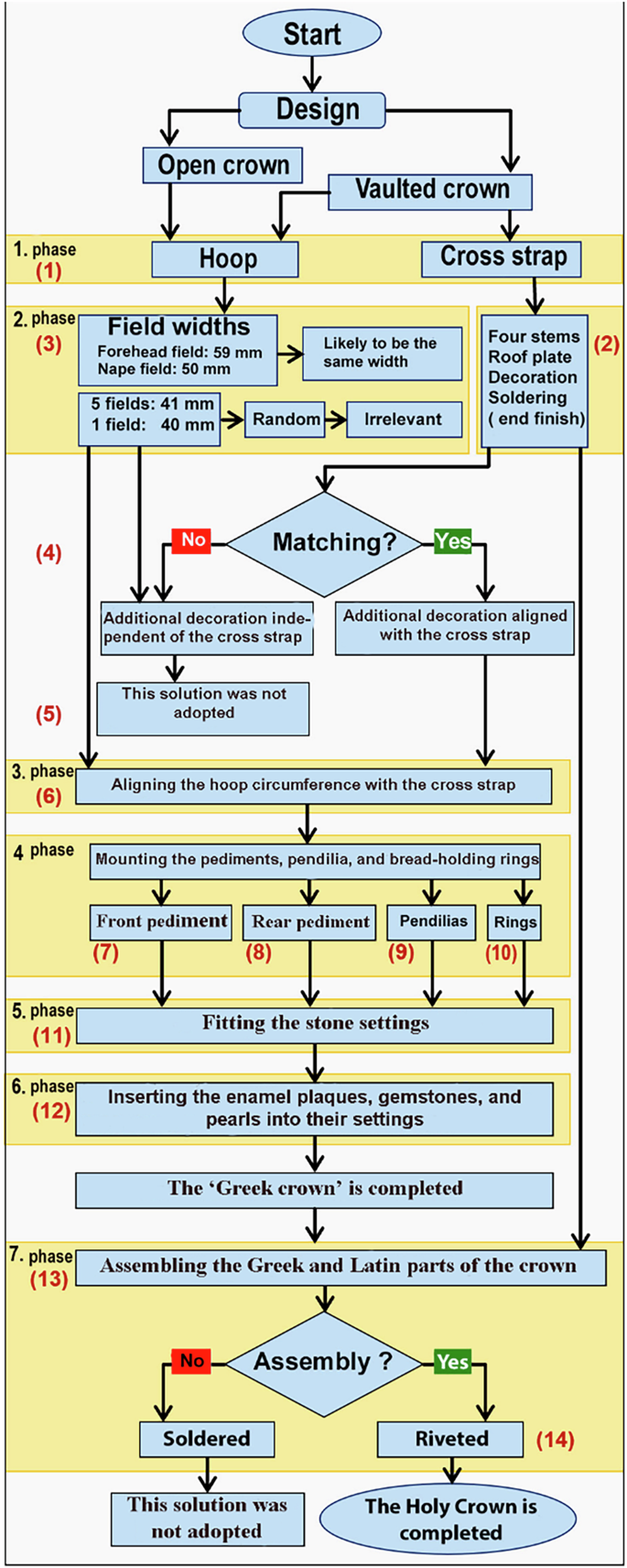

For mechanical assessment, a solid-model CAD reconstruction was created30, allowing component-level modelling and iterative testing of the assembly sequence. Geometric fit, interference risks, tool accessibility, and fabrication feasibility were systematically assessed, and inconsistent sequences were discarded. This process confirmed manufacturing logic and structural feasibility while enabling subsequent load testing, mass estimation, and material-property assignment32 (see Supplementary Fig. S2). All geometric data underlying the model reconstruction are supplied in Supplementary S3, forming the quantitative basis for the CAD illustrations. A schematic of the technological sequence appears in Fig. 5.

The current study addresses primarily the heritage-science community. Earlier engineering analyses identified the cross-strap as the key structural element, to which the circlet was fitted. Although the chronological relationship between these two components—whether the circlet preceded, coincided with, or followed the cross-strap—remains uncertain, features such as the diadem, bead rows, pendilia, and the prominent rear gemstone could only have been added after the cross-strap junctions on the circlet were fixed (see video: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29232536).

Key observations from the visual and digital analysis

The Holy Crown was conceived as a unified artefact composed of two precisely harmonised parts.

Its principal structural component is the cross-strap, designed and fitted in direct relation to the roof plate.

The hoop crown attained its present configuration through successive structural phases.

The eight plique-à-jour enamel plaques were produced with strict bilateral symmetry. Ornamental features—including the diadem, pendilia loops, bead rings, and terminal joints of the circlet—are geometrically aligned with the cross-strap arms.

Collectively, these observations demonstrate that the Holy Crown is not a fortuitous assemblage but a purpose-built, systematically constructed artefact whose structural design demands critical consideration when addressing its origin and chronology.

Technical background of enamelling

Identifying the technological characteristics of enamelling is essential for interpreting the Holy Crown within a scientifically grounded framework. Technical solutions are often associated with distinct historical styles, offering crucial evidence for dating and provenance. The Holy Crown incorporates nineteen figurative plaques executed in the double-layer recessed technique, complemented by eight plique-à-jour panels. Of these, ten plaques bear Greek inscriptions and stylistic traits of Byzantine origin, eight feature Latin inscriptions, and one uninscribed plaque displays Western workmanship. This distribution reflects intensive interaction between Eastern and Western traditions while maintaining clear stylistic identities.

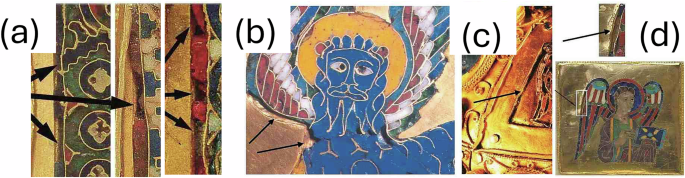

Despite extensive art-historical scholarship, the technological distinctions between Western and Byzantine enamelling remain insufficiently defined. Comparative analysis indicates that these differences primarily result from variations in manufacturing sequence. In Western practice, the upper plate was cut to form motif openings, and the two plates were first soldered together. The lower plate was then recessed to secure the cloisonné wires, with shallow cavities (0.2–1 mm) ensuring accurate placement. The wires were usually fixed before the successive enamel layers were applied. The apostolic plaques of the Crown, as well as the Andreas Tragaltar (Fig. 6) and plaques from Trier and Essen, exemplify this method.

Byzantine workshops followed a different procedure: the pattern was marked on both plates, the upper cut along the contours, and the lower recessed—often beyond the motif openings. The plates were then soldered together to create an integrated structural base (Fig. 7)15,33.

A central outcome of this study is the development of diagnostic criteria for identifying double-layer recessed enamel plaques from visible surfaces alone. The Greek-inscribed examples (Fig. 8) display irregular letter shapes and variable line thickness; each letter was cut individually rather than from a stencil. Such irregularities, together with wires and enamel extending beneath the upper plate, produced bulges and distortions during soldering and firing. Subsequent polishing occasionally damaged the upper plate, as visible in Figs. 7–8. Features such as chipped edges, enamel seepage, and uneven inscriptions distinguish these plaques from single-layer recessed works. Moreover, there is no evidence of inscriptions engraved outside enamelled fields north of the Alps, underlining the singular character of Byzantine craftsmanship.

The double-layer recessed method predominated during the 10th–11th centuries and represents one of the most characteristic technologies of its time, though not the only one in use. In Western Europe, the alternative Vollschmelz (German for “full-fusion”) technique covered the entire surface with enamel, leaving no exposed metal. During the reign of Constantine Monomachos, a simplified single-layer recessed process emerged in Byzantium, distinguished by cavities cut directly into a single metal sheet. These developments demonstrate that enamelling practices were more diverse than the traditional East–West division implies.

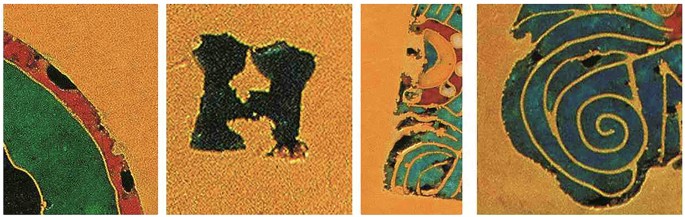

The plique-à-jour process (“admitting daylight”) ranks among the most sophisticated medieval enamelling techniques. It involves firing translucent enamel into open cells without a backing plate, producing an effect akin to stained glass (Fig. 9). Initially, the enamel is applied to a temporary substrate—such as mica or foil—and repeatedly fired; the substrate is later removed by boiling, etching, or abrasion, leaving the enamel suspended within metal partitions34.

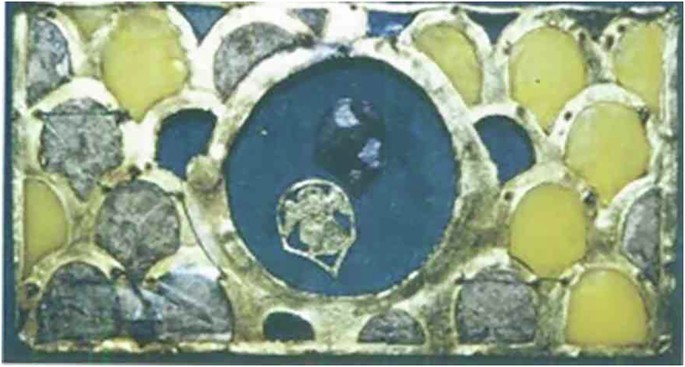

Examination of the diadem’s plique-à-jour plaques reveals an intricate gold-wire lattice forming a scale-like pattern (approx. 4 × 1 mm) bounded by triangular and semicircular frames. A closely related design appears on the Andreas Tragaltar, where it is enclosed in a rectangular field with a central circular aperture (Fig. 10)35.

Such enamel plaques are exceptionally rare in metalwork from around the first millennium, with no close parallels in either Byzantine or Western European art. The Andreas Tragaltar (Fig. 11a and b) thus provides the closest comparative example. In both objects, enamel was fused in open filigree cells without a backing plate—an exemplary manifestation of the plique-à-jour technique. Their presence on the Holy Crown provides a decisive technological indicator for establishing chronology and workshop attribution, a point to which the discussion will return below.

From Trier–Essen to Byzantium: enamelling traditions and the chronology of the Holy Crown

This section integrates art-historical interpretation with technical evidence to establish the temporal and spatial context of the Holy Crown’s creation. The cross-strap serves as the defining structural feature, providing a terminus post quem for the Crown.

By the late tenth century, diminishing gold resources in the East Frankish Empire prompted notable shifts in Western European enamelling. The two-layer recessed method was gradually supplanted by champlevé during the eleventh century36,37. The production of enamels fused into gold ceased by the 1030 s, placing the Latin-inscribed plaques on the cross-strap most plausibly within the period 970–100038. Multiple scholars—including Buckton35, Bock39, Ipolyi40, Uhlirz41, von Falke42, Koller43, Bárányné-Oberschall44, and Eckenfels-Kunst45—have attributed these plaques to the Trier–Essen workshops active before the turn of the millennium. Microscopic examination of the roof plate has revealed traces of red enamel, implying that full enamelling may once have been present.

The hoop crown was fashioned from a lower-purity gold alloy shaped into a thickened band, with decorative elements joined by hard soldering. Although structurally sound, this method often produced uneven seams and occasionally weakened earlier joints during reheating23. Oxidation marks are visible around several soldered areas, and imprecise joints—particularly in deeper recesses—were subsequently concealed with gold paint or gold leaf to mask imperfections and achieve a uniform surface appearance.

Within Byzantium, double-layer recessed enamelling prevailed in the late tenth century but was replaced in the eleventh by single-layer techniques featuring opaque enamels, denser cloisonné wires, and a growing use of silver substrates. The translucency and brilliance of the Crown’s enamels—particularly the vivid emerald green46—suggest production in high-prestige Byzantine or Western ateliers prior to the dominance of opaque methods.

Ten Greek-inscribed plaques exemplify Byzantine craftsmanship of the tenth and early eleventh centuries. The imperial portraits of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus and Michael VII Doukas (1071–1078) are, however, likely later additions.

Given the concentration of both Western and Byzantine enamels in the imperial treasury of the East Frankish realm before 1000, it is plausible that the Crown originated within that cultural sphere. Further material and optical analyses are required to clarify the precise relationship between the hoop crown and the cross-strap. Current evidence suggests that both components were conceived in tandem or produced in close succession; this evidence does not support the adaptation of an older circlet, but rather indicates deliberate design coherence.

Traces of aging, repairs, and modifications on the Holy Crown

Over the centuries, the Holy Crown has undergone progressive mechanical fatigue. Detailed examination revealed five complete fractures and three partial cracks in the cross-strap arms, located near the junctions with the roof plate and beneath the upper enamel plaques.

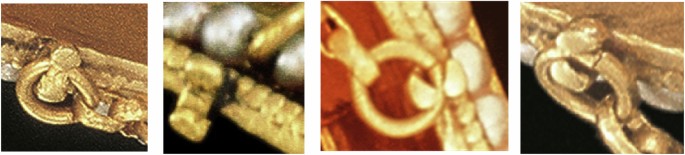

Fractographic inspection of the edges—showing serration and roughly 90° deflection—indicates fatigue failure caused by repeated subsidence of the cross-strap followed by subsequent straightening. Such degradation most probably resulted from vibration during transport and handling. High-purity gold, though initially ductile, hardens under recurrent bending, developing microcracks that eventually propagate into structural failure; these elements were repeatedly repaired. Long-term wear is also visible in the original suspension loops of the pendilia, where pronounced abrasion and occasional breakage have been recorded (Fig. 12).

The enamel plaque depicting Emperor Michael VII Doukas preserves evidence that it replaced an earlier image. Historical sources, including Bonfini47 as cited by T. Katona5, note that the cracked gemstone beneath this plaque was used under Matthias Corvinus (1458–1490) as a sign of authenticity and later replaced by order of Matthias II (1608–1619). As removal of a gem mount required substantial intervention, the overlying enamel plaque was likely damaged in the process. Péter Révay, crown guard at the coronation of Matthias II, reported that the rear plaque had originally depicted the Virgin Mary48.

Photogrammetric analysis has revealed further irregularities. The plaque showing Saint Bartholomew, now positioned behind the Pantokrator, displays extensive deterioration. According to the biblical sequence in Acts49, the first seven Apostles plus Paul should appear in order along the cross-strap; however, the plaques of Bartholomew and Thomas are transposed. Installation of the Doukas portrait required four drill holes through both the mount and the cross-strap50. As the Thomas plaque along this axis remains undamaged (Fig. 13), it cannot have been present during drilling. This evidence demonstrates that the exchange of the Thomas and Bartholomew plaques, together with the insertion of the Doukas image, must have occurred during this phase of alteration.

The Doukas plaque does not match its current setting, confirming that it was originally made for another position. While produced in Byzantium during the reign of Michael VII (1071–1078), its inclusion in the Crown was a later intervention. It therefore cannot be associated with the manufacture of the hoop crown in his reign, contrary to prevailing opinion in Hungarian scholarship.

The documented structural damage—including fractures, fatigue cracking, plaque substitution, and subsequent alterations—forms a key basis for reconstructing the Crown’s mechanical and historical evolution. Additional but less significant changes include the tilted cross, variations in the number and placement of pendilia, and replacement of gemstones on the hoop crown. Certain details remain unresolved, such as residual wire fragments and small perforations on the diadem, whose purpose is yet undetermined.

The findings presented in Sections 3.1–3.4 should be regarded as working hypotheses; subsequent sections address measures taken to improve reliability and to minimise potential sources of error.

Validation of Holy Crown archaeoengineering investigations

In engineering, a technological procedure is considered validated only when it demonstrates reproducibility under controlled conditions, with each iteration producing equivalent structural and functional results. This requirement was fulfilled through the fabrication of a full-scale replica reproducing every essential feature of the Holy Crown, thus confirming the feasibility of the proposed construction sequence. The replica is publicly accessible at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29234825.

This reconstruction exceeds the limitations of a conventional scale model: its significance lies in the precise correspondence between the diadem, circlet ornaments, and cross-strap, achieved through a predefined technological protocol. The technological flowchart first presented by the author at a Romanian conference in 202231 and later refined (see Section 3.1, Fig. 5) now serves as the procedural framework for the replica’s manufacture, with red numerals indicating consecutive operations within distinct phases.

Phase 1–2

(1–2) The minor deviations of the cross-strap arms from a perfect right angle were reproduced by precision drafting. The magnitude of angular divergence is less significant than its deliberate presence, reflecting the irregularities observed on the original artefact. The arms were designed and executed in reference to the roof plate, resulting in the cross-strap being produced as a single finished unit.

(1–3) The circlet was divided with exact proportions. A replica matching the original diameter was created, with front and rear gemstone fields of 59 mm, six lateral fields of 79.4 mm, and two enamel-plaque mounts of 38.7 mm. Although precise, the total circumference exceeded the original by 9 mm (see Supplementary S3).

(4) The cross-strap was attached to the divided circlet along the axis defined by two opposing arms. Geometric accuracy was maintained along this axis, while the perpendicular one had to be derived, producing slight inaccuracy.

(5) The goldsmith selected the lateral alignment, which inevitably introduced rotational displacement of the front and rear orientations proportional to the accumulated tolerances.

Phase 3

(6) To correct this misalignment, the rear centreline of the cross-strap was marked on the circlet. A 9 mm segment was removed from the left side, the right end drawn in to meet it, and both joined by a single solder seam.

Phase 4

(7) The central plaque mount depicting Christ was aligned with the frontal axis of the cross-strap, followed by adjustment of the triangular and arched plique-à-jour mounts.

(8) The enamel mount of Emperor Michael VII Doukas is aligned with the axis of the rear cross-strap arm.

(9) The pendilia were affixed in alignment with the arms of the cross-strap.

(10) The upper and lower frontal bead-holding rings were installed, likewise aligned with the front arm of the cross-strap.

Phase 5

(11) Gemstone mounts were positioned.

Phase 6

(12) Enamel plaques, missing pearls, and gemstones were added; the larger stones were set only after soldering the circlet ends.

Phase 7

(13) Completion of the hoop crown.

(14) Final assembly joined the hoop crown and cross-strap using fine screws—a deliberate deviation from the original, which employed rivets.

During the original manufacture, the goldsmith faced a crucial decision: whether to align the diadem and decorative elements with the cross-strap or with the circlet divisions. Alignment with the cross-strap was evidently chosen; selecting the alternative would have rendered the construction geometrically inconsistent.

FMEA as the sole conclusive validation of the Holy Crown’s manufacturing hypothesis

Application of Failure Mode and Effects Analysis (FMEA) to the Holy Crown begins by evaluating alternative scenarios within the established technological sequence. This case offers a distinct analytical advantage: only two plausible pathways exist. The Crown consists of two major components joined solely at the final manufacturing stage. The possible options are therefore either that the hoop crown was adjusted to fit the cross-strap, as previously demonstrated, or conversely, that the cross-strap was adapted to the hoop crown.

Examined Failure Mode: The cross-strap was adjusted to the hoop crown. This configuration reflects the alternative assembly approach currently underpinning the predominant hypothesis in Hungarian academic research.

Initial Conditions: The segments of the circlet were constructed with exact geometric precision; relative to these, the diadem, the pendilia, and the bead-holding rings were attached with slightly offset yet inseparable joints.

Expected Effects: In order to align the four arms of the cross-strap with their original positions on the Crown, each arm would have to be mounted and aligned independently of the others, without a unified geometric reference point.

Anticipated Difficulties: Owing to the differing lengths and curvatures of the cross-strap arms, together with their asymmetric positioning, precise alignment with the designated attachment points on the centrally located square roof plate is technically infeasible.

Physical Traces: It is essential to note that the asymmetrical ornaments of the hoop crown—such as the diadem, the pendilia, and the bead-holding rings—are not positioned arbitrarily on the circlet. Their placement is geometrically determined by the orientation of the cross-strap arms. Any assembly scenario that does not observe this interdependence is therefore structurally impossible.

Assessment: The diadem, together with the frontal bead-holding rings and pendilia suspension loops, is aligned with the central axes of the cross-strap arms rather than with the divisions of the circlet. This configuration confirms that the cross-strap governs the overall geometry of the Crown. Consequently, the alternative hypothesis—that the hoop crown constituted the primary structural element—is not supported.

Integrating archaeoengineering methods within the Holy Crown achaeometric analysis

The Holy Crown of Hungary is granted the highest level of state protection. Since 1 January 2000, it has been displayed in the Parliament Building under continuous ceremonial guard, with direct access permitted only by explicit authorisation of the Holy Crown Board. This body, comprising senior governmental and academic representatives, must approve all procedures in advance. A 2005 resolution established the governing principles: every investigation must be demonstrably harmless to the Crown, carried out in situ, and justified by its scientific relevance and anticipated contribution to knowledge.

This section outlines the first project designed to meet these stringent requirements, employing exclusively non-invasive analytical methods to complement and verify previous archaeoengineering investigations51,52. The programme was strictly limited to procedures deemed necessary yet sufficient, grouped into two categories: advanced photographic documentation and targeted material characterisation.

To address unresolved issues, a focused imaging campaign was proposed, incorporating endoscopic photography of previously inaccessible structural zones. The recommended system, the Phase One XT IQ4 150 MP camera53, is capable of capturing ultra-high-resolution data. Documentation concentrated on technically significant and debated areas, including:

The portrait plaque of Emperor Michael VII Doukas and its surroundings;

The deformation and fastening of the tilted cross;

The junction between circlet and diadem, to assess uniformity of alloy composition;

The Apostle plaques of Thomas and Bartholomew for detailed examination;

Cases discussed in Sections 3.1 and 3.4, recorded at the highest optical resolution and extended depth of field.

Multispectral imaging, recording reflectance across ultraviolet, visible, and infrared ranges, reveals features invisible to the naked eye. It has proven particularly effective for enamel and metal surfaces, enabling identification of:

Traces of wear, fatigue, and sub-surface repairs concealed by later gilding;

Restoration layers and stratigraphy within enamel plaques;

Pigment composition and distribution;

Differences among gold alloys and plaque types;

Gemstone quality and evidence of surface treatment;

Oxidation, sulfidation, and corrosion films;

Differentiation between original and restored components;

Comparative typological characteristics.

By providing a spectral fingerprint of the Crown’s materials, this method enhances both technological interpretation and conservation planning54. Its effectiveness depends on dense measurement grids and careful instrument calibration.

Modern imaging technologies further allow the creation of ultra-high-resolution three-dimensional models, facilitating virtual examination of the Crown at microscopic scale. Photogrammetric reconstructions, derived from calibrated multi-angle images, document surface irregularities, tool marks, deformations, and hidden structural details55. Although these lack the parametric functions of CAD systems, they supply essential geometric input for digital design models. Such datasets provide reference standards for monitoring long-term changes, supporting authentication, and guiding future conservation strategies.

For compositional analysis, XRF spectroscopy was employed. Although the Crown’s inorganic nature precludes direct dating, alloy analysis of the metals, enamels, gemstones, and pearls yields crucial information on provenance, technology, and chronology. Access to international databases enables contextual and comparative evaluation of alloy compositions56. The Bruker TRACER 5 portable XRF unit57 was selected, as XRF remains the most widely used non-invasive elemental method. Although µ-Raman spectroscopy could provide valuable molecular information, it was not proposed as a first-step method, as its focused laser excitation may pose a risk to the highly sensitive translucent enamels of the Holy Crown.

In practice, comparing the alloys of separate mounts—such as those linking the hoop crown and cross-strap—or examining the glass composition of translucent enamels, particularly when contrasting the diadem with the apostolic plique-à-jour plaques, may provide decisive evidence of a shared workshop origin. Such findings would substantiate interpretations of the Crown as a unified and intentionally integrated artefact56. Ideally, these analyses should form part of an extended conservation framework.

In practice, comparing the metal alloys of the settings of the hoop crown and the cross-strap, as well as analysing the glass composition of the translucent enamels—particularly through the comparison of the diadem’s plique-à-jour panels with the enamel material of the apostolic plaques—may yield decisive evidence for a common workshop origin. Such results would reinforce the interpretation that the Holy Crown was conceived as a deliberately unified and structurally integrated artefact. In the most favourable case, these findings could demonstrate that the cross-strap and the hoop crown were produced within the same workshop.

Supplementary Figs. S7–S17 provide additional photographic records, and an explanatory video is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29867699.