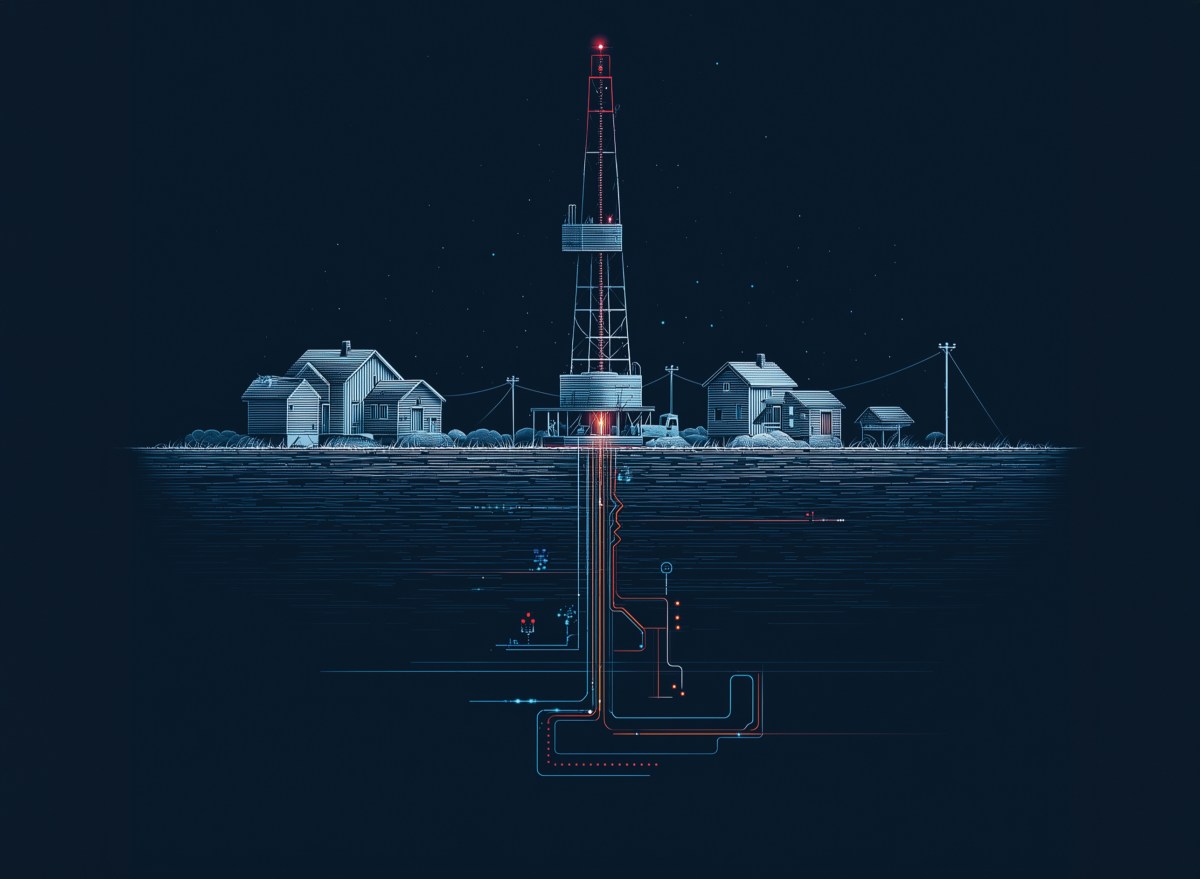

In-demand AI data centers require huge amounts of energy, and companies are turning to areas rich in natural gas (like lee county) for possible solutions

By Gordon Anderson | gordon@rantnc.com

If you’re new to Lee County, fracking might not be a term you’ve heard a whole lot of in the context of local politics. But there was a time not long ago when fracking — shorthand for hydraulic fracturing, a method used to release natural gas and other resources by injecting high-pressure fluid into underground rock formations — was a hot topic both across the state and in the general area.

Lee and Chatham counties sit atop shale gas deposits identified by state geologists, and for much of the early 2010s, there was a contingent both locally and in the state capitol working to allow those with mineral rights in the area to get to it. Proponents said it would create new wealth, new economic activity and a clean burning energy source right here at home.

Detractors, however, pointed to reports of environmental harm in places like Pennsylvania and Oklahoma, where fracking has been undertaken on a large scale. There were widely circulated reports at the time of contaminated water — including claims of flammable tap water. Even earthquakes have been tentatively linked to fracking. Also, mineral rights are often severed from land rights, meaning one can theoretically have the right to access natural gas that’s beneath land that isn’t theirs.

There’s not enough space to rehash that debate in its entirety, but it had gone mostly quiet by the turn of the 2020s. Lee County was under a locally-passed fracking moratorium through the last half of the 2010s, but even after it expired, there’s been no commercial hydraulic fracturing here or elsewhere in North Carolina outside of test and exploratory wells.

But the debate about fracking, it seems, wasn’t over. Just dormant.

Deep River Data and the Butler Well

Things came spilling back into the public on Nov. 1, when Inside Climate News published a report indicating Alamance County-based company Deep River Data wanted to access natural gas from Butler Well No. 3, which is situated in the woods between U.S. 421 and Cumnock Road near the Lee-Chatham County line and use it to power a data center for artificial intelligence here.

The story identified Deep River Data as having “connections with the cryptocurrency industry” and detailed connections its officers have both in business and government.

“Company adviser Dan Spuller, who is both a crypto entrepreneur and a natural gas landman, contacted the state Oil & Gas Commission in September about applying for a drilling unit, a parcel of land where drilling would occur,” the story read. “He said the natural gas would be for a data center to power ‘AI workloads,’ not crypto mining. Both applications are energy-intensive, running server farms around the clock to power streams of computer computations.”

The ICN piece reports Spuller writing “we want to submit a packet that is complete on first impression — avoiding delays and making the Commission’s review as straightforward as possible.”

The news spread quickly – the article and others like it were shared on social media, often with calls to action attached. In December, that action spilled off of the internet and into real life. At meetings of the Sanford City Council (Dec. 2) and the Lee County Board of Commissioners (Dec. 15) nearly 20 people addressed the two boards, urging both to put a stop to the idea as quickly as possible.

Although Spuller is quoted in the Inside Climate News piece as saying Deep River Data plans to use “conventional drilling, rather than fracking,” those who appeared before local governing boards in December unanimously asked for moratoriums to be enacted on both data centers and fracking.

Community concerns

“Sanford has a large population of residents that would be harmed by fracking,” area resident Keely Puricz told the city council on Dec. 2, holding up a map of the area surrounding Butler Well No. 3. “I’m speaking before it’s too late. The risk of using an antiquated well in itself is frightening. This well has not had regular inspections … and at recent meetings of the Oil & Gas Commission, the (Department of Environmental Quality) admitted they only had one employee to review the rules versus the four or five they had 10 years ago.”

Sam Kauffman told the council he’s originally from Oklahoma, and “grew up during the oil and gas boom.”

“I’ve seen the wells, I’ve seen the fracking — it’s not worth it,” he said. “You’ll end up in an Erin Brokovich situation where pollution is inevitable.

“It’s not if, it’s when.”

The county Board of Commissioners heard more of the same less than two weeks later.

“I know this will be a great monetary gain for the man that’s interested in having this in our county,” Christine Morgan told the commissioners on Dec. 15. “But we all deserve to have clean air and clean water. I feel like that’s our right. God made the planet one way, and we have done enough in our destructive selves.”

Jennifer Garner told the commissioners she was born and raised in Sanford, and had “moved away a couple times.”

“Every time I came back I’d see the growth and the revitalization that’s been done in my favorite city and my favorite downtown,” she said. “It seems like a gross, counterproductive measure to put all that into our community just to destroy it, just to open the literal floodgates of contamination that would be brought by frackinig.”

The message was clear: There’s at least a part of the Lee County community that’s not only adamantly opposed to fracking, but also data centers in general, and they’re not afraid to show up and talk about it.

Permits, utilities and regulatory reality

There’s a wrinkle to the concern over drilling for AI in Lee County. Not a single permit has been requested for any of the things outlined in the Nov. 1 story — not at the state level or the local level.

Not to cast doubt on the ICN piece, which is sourced from emails received under a request for public information. There’s no reason to doubt those are real or that Deep River Data has at least explored the idea it described. But potential moratoriums aside, there’s nothing for local government to do right now with regards to the rumored project, because nobody’s asked for anything. At least not on paper, according to Kirk Smith, Republican chairman for the Lee County Board of Commissioners.

“There are no permit requests before the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality to access the natural gas in Lee County nor the Butler #3 gas well,” Smith told The Rant via email in December. “There are no permit requests for a drill pad nor for an access road with the NC DOT. There are no permit requests for extraction and the ultimate closing of the well. The Lee County Technical Review Committee has not received any plans for a proposed data center nor has the Sanford Area Growth Alliance received any Requests for Information with the intent of establishing a data center. The Lee County Joint Planning Commission gave instructions for the staff to research possible modifications to the Unified Development Ordinance addressing data centers.”

Further, utilities are increasingly wary of data centers — they use an inordinate amount of power after all, and companies like Duke Energy are more regularly asking for sizable, up front monetary commitments from those who want to operate one. It’s possible the rumored project would be powered by a private, onsite power plant of its own, but that would still require approval from Duke for interconnection and backup service. So, nowhere near impossible, but not as simple as it sounds either.

Smith’s statement could be seen as cold water thrown on the idea of drilling for natural gas at Butler No. 3 and using it to power a data center. But Smith also threw cold water on the idea of any kind of moratorium on fracking and/or data centers.

“The demand to establish a moratorium thus blocking land owners from generating wealth from their property, is on its face dictatorial and rooted in an authoritarian regime most associated with Marxists,” he wrote. “While on the subject, recent hearings in the U.S. Congress reveal the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is funding environmental groups opposing ‘data centers.’

“The CCP is home to cheap and plentiful electricity generated by coal fired electrical plants (do you recall the air pollution leading up to the Beijing Olympics?). What better way for China to lead and dominate the Artificial Intelligence industry. Our Constitutional purpose as a governing body is to ‘Protect Life, Liberty, and Property Rights.’ Any moratorium violates that fundamental purpose of our Constitutional Republic protecting property rights.”

However, local fracking moratoriums in North Carolina aren’t explicitly bans on the practices — they’re temporary pauses that allow governments to review potential impacts. The state retains ultimate regulatory authority.

Data centers: A separate but linked debate

Jimmy Randolph, CEO of the Sanford Area Growth Alliance — a public-private partnership that houses the area chamber of commerce as well as the county’s economic development operation — similarly said he hasn’t heard much, if any, credible talk about the project. He was careful to distinguish the issues opponents are raising from one another.

“There’s a conversation to be had about data centers and the benefits and utility they may be able to provide to communities like ours. The right data center project could absolutely be a positive for Sanford and Lee County. Fracking is an entirely separate conversation with concerns and questions that are unique to that issue,” he said. “That being said, SAGA has not received or been asked to provide any information about the specific project referenced in recent media reports and in front of the city council and the county commissioners, so it would be inappropriate to speculate.”

The debate over data centers includes controversies of its own — controversies which are separate from the debate over fracking. They’ve been shown to bring increased tax revenue and some number of jobs, although nowhere near the number a more traditional industry might offer. But there have also been concerns about water usage and other environmental concerns (for his part, Smith disputed entirely the idea that data centers “consume enormous amounts of water,” calling the idea “fear mongering”).

So it’s not surprising that news reports are common lately which describe local governments proposing and enacting standards surrounding data centers.

A recent piece in the Midland Daily News in Texas described efforts by the government of Bay City, Texas (population of around 18,000) to look at concerns like “maximum facility size and acreage of the site; power demand threshold and utility capacity review, water usage limits and cooling method requirements; noise, lighting, buffering and setback standards; site location criteria and zoning compatibility; phased development and expansion limitations; emergency response, resiliency and decommissioning plans; and community benefit and infrastructure impact considerations.”

North Carolina law does allow local governments to regulate land use through zoning and other methods, making standards similar to those being explored in Bay City theory possible.

What comes next?

It’s too early for alarm or worry about Lee County’s potential role in the country’s AI boom. There’s too much that nobody knows at this point. Data centers and fracking are separate issues, but both have sparked local debate about environmental impacts, utility use and community standards. Those addressing local governments over the matter have the right idea — they’re making their stance known now while the issue gathers on horizon, instead of waiting for it unpack its bags.

Puricz, who spoke before both the city on Dec. 2, told the Board of Commissioners on Dec. 15 about recent fracking activity in Pennsylvania and cited a data center moratorium in Wisconsin that allowed “local government to develop suitable ordinances regulating an industry’s activities.”

“Since Dec. 4, one (Pennsylvania fracking) company had 360,000 gallons of drilling fluid lost into the local coal pockets,” she said.

Another speaker before the county commissioners on Dec. 15 was Debbie Hall, who acknowledged that no applications have been filed. “You know and we all know that the wheels are turning,” she said. “Drilling, fracking and data centers are linked to many hazards. You are the people that can help us, and we’re asking you to do that.”

This issue isn’t likely to go away anytime soon, regardless of what happens with the rumored project that kicked off what appears to be a revival in local anti fracking activity. More is coming in the weeks, months and years ahead. The Lee County Board of Commissioners as of this writing is scheduled to meet on Jan. 5, which is The Rant Monthly’s publication date. Clean Water for NC, a state based water advocacy group, published a blog on Dec. 17 urging interested parties to attend and ask for a moratorium on fracking and data centers.

Related