A year ago, I traveled to Egypt with 12 other pilgrims from Wake Forest University School of Divinity to learn about the country’s rich religious history.

Our mostly Christian group spent much of our time learning about religions other than Christianity. We toured Islamic mosques, including the Mosque of Muhammad Ali, and walked through pharaonic tombs to see ancient hieroglyphs portraying mythological beliefs about the afterlife.

Mallory Challis

But tucked away in the Old Cairo neighborhood of Al Dayoura is some rich — and very relevant — Christian history at the Church of Abu Sirga.

Coptic Christian legend says the Holy family took refuge for three months in the area that is now the basement of this church while fleeing King Herod’s state-sanctioned violence against Jewish babies. Because of this, it is nicknamed “the Cavern Church.” Signage at Abu Sirga is explicit about what this means: “On this sacred site, the Holy Family, Mary, Joseph and the Christ Child were given asylum to fulfill Hosea’s prophecy.”

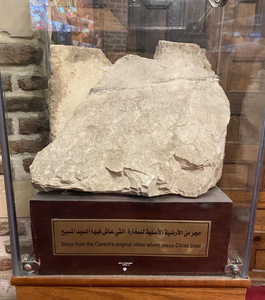

Our group was able to walk down to see the space where the holy refugee family purportedly lived while protecting their son from this violence. Various parts of the church are sectioned off behind glass, including a piece of the original ground where the holy family supposedly walked, and the well from which they drank water.

Basement entrance in Cavern Church

Unfortunately, it is difficult to prove archaeologically this was the exact spot where the holy family lived while seeking asylum in Egypt. However, Coptic Christian tradition recognizes the Church of Abu Sirga as a memorial of this part of Jesus’ birth narrative. It serves as a physical representation of the fact that the family survived because they took refuge in a foreign country.

In fact, there is imagery of the holy refugee family all over Coptic Cairo.

They are often depicted with Mary and Baby Jesus riding a donkey while Joseph leads. And although the archeological evidence may be shaky, this imagery serves as evidence of a real and powerful religious tradition that honors Jesus and his family’s status as asylum-seekers.

Although the biblical narrative makes it clear they were Israel natives, Coptic Christian tradition embraces the family and their presence in Egypt as an important part of its history. In this interpretive world, Jesus’ identity is irrevocably tied to his immigration status.

Unlike current conflicts in the United States, this identity is explicit, amplified and celebrated.

“Our asylum-seeking Jesus has somehow been transformed by Americans into an idol used to justify violence against immigrants.”

There is nothing to hide about the holy family’s immigration status for Coptic Christians because they are proud to have offered them shelter from political violence and injustice. They honor Mary and Joseph’s bravery as parents who could have accepted their son’s fate at the hands of empire, but instead chose to take the political risk of seeking shelter in a foreign place.

As an American tourist looking back on my photos of all this imagery, I wonder why we cannot live with the same conviction. Why our administration, which often uses the name of Jesus in political propaganda, is treating immigrants as if they are the worst possible thing to step foot in our presence.

Stone from cavern

Our asylum-seeking Jesus has somehow been transformed by Americans into an idol used to justify violence against immigrants.

And I wonder what we ought to do about it.

I don’t have to tell you about the dangerously violent state of immigration in the United States right now. Other BNG journalists like Mara Richards Bim, Jeff Brumley and Mark Wingfield already have been on the ground covering these important stories.

But I would like to ask: What does Jesus’ identity as an asylum-seeker mean for our faith?

Really. I want to consider this deeply as celebrate Jesus’ scandalous birth narrative.

How ought we live with the fact that God chose to enter the world by being born into a family who had to live as refugees? How does God’s risky and taboo immigration status change the way our faith encounters our current world?

“How does God’s risky and taboo immigration status change the way our faith encounters our current world?”

And who are we in this story? While we want to believe we would be the kind Egyptians who welcomed the Holy family into safe community, I fear America today represents Herod and his tyrannical violence.

Reflecting on these questions, I think about the artistic displays of the holy family I see in my own communities.

They are almost always depictions of the manger scene: White-passing Mary and Joseph are smiling while white-passing Baby Jesus lays peacefully in a bed of fresh hay. The farm animals gaze upon him in awe. There are three wisemen, and only one of them is brown-skinned.

And although this is a very beautiful scene, it is unrealistic.

Jesus’ birth was scandalous. Mary and Joseph were rejected by the inn and offered a disrespectful lodging offer they had no choice but to take. I am certain the farm animals were not clean, nor were they trained to be well-behaved during a live birth. The surrounding hay probably was covered in bodily fluids from the birthing process. And nobody involved was white.

Our sanitized version of the Jesus story does the opposite of what imagery in Coptic Cairo does by removing the sense of risk, the danger and taboo nature of it. We praise this unrealistic image of Jesus and forget these first stages of his life were messy and political.

We are too far removed from Jesus’ identity as an immigrant, and it shows.

Mallory Challis is a former BNG Clemons Fellow who is a third-year master of divinity student at Wake Forest University School of Divinity.