CALGARY — When Canadian leaders were looking to present a common front against U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariff threats early last this year, Alberta Premier Danielle Smith struck a distinctly different tone.

While other premiers were getting behind a potential $155-billion counter-tariff package, Smith urged restraint. As Ontario Premier Doug Ford threatened to shut off power to the U.S., the Alberta leader emphasized America’s need for cheap crude oil, her province’s main export. Smith lobbied central Trump administration figures like U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright and U.S. Interior Secretary Doug Burgum, and even visited Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida a week before his inauguration.

Talking Points

A closer look at U.S.-Canada trade data illustrates the extent of the province’s privileged position

With Trump in charge, however, experts warn against getting too comfortable

Nearly a year later, Alberta’s trade position with the U.S. is no less singular than its leader’s tactics. The province has thus far sidestepped the worst of Trump’s trade war, even as tariffs batter provinces like Ontario, B.C. and Quebec.

To get a sharper sense of the situation, The Logic analyzed trade data to gauge Alberta’s relative exposure to U.S. duties. The results show that the province typically exports a small share of the Canadian goods hit with Section 232 tariffs. That is largely due to the U.S. decision not to put similar national-security tariffs on oil and gas, but the data suggests there is more to the story. Canada-U.S. trade figures from the five years before Trump returned to the White House show the province is far less vulnerable to the trade war than most others—and will remain so even if Trump makes good on his threat to slap tariffs on other sectors.

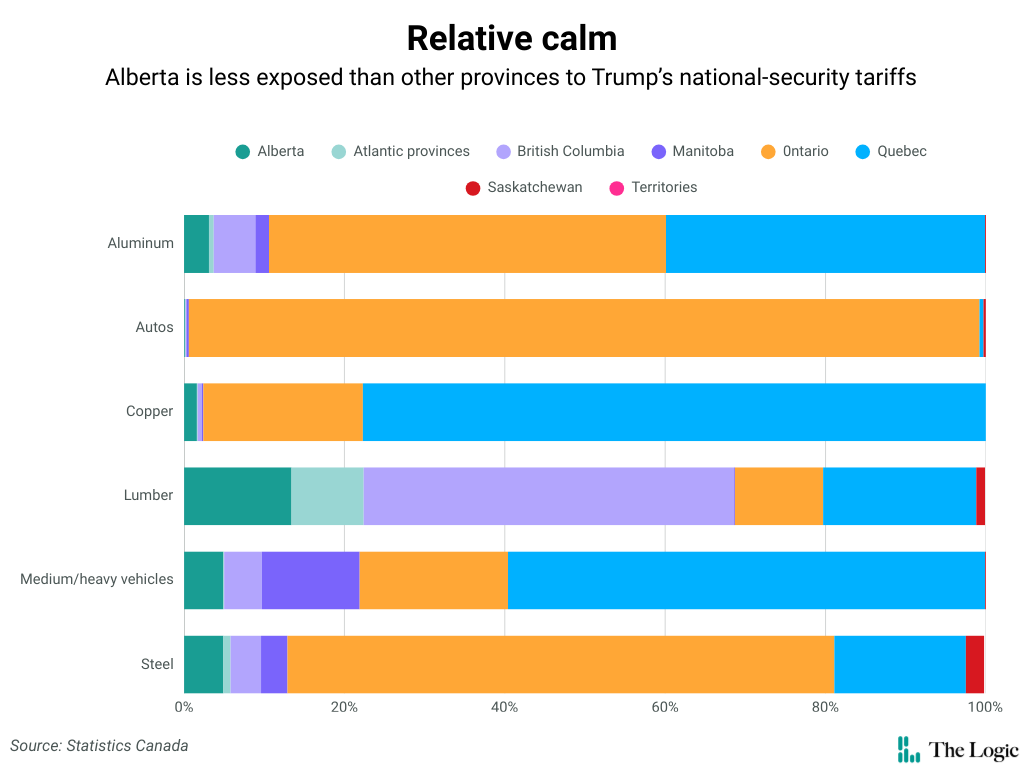

When it comes to steel and most of the derivatives now hit with 50 per cent tariffs, for example, Alberta exported an annual average of $804 million to the U.S. from 2020 to 2024. That accounted for about five per cent of the average value of Canada’s total exports of those products. Ontario, on the other hand, accounted for about 68 per cent of those exports, equalling an average $11.1 billion per year.

The discrepancy is predictably starker when it comes to autos, a crown jewel of central Canada’s industrial belt. Ontario shipped an average of about $40 billion worth of autos to the U.S. per year over that period—nearly 99 per cent of Canada’s auto exports south of the border. (The Logic’s analysis did not include auto parts subject to Section 232 tariffs, as there is currently a full exemption for parts traded under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement.)

Alberta is more exposed when it comes to lumber products now subject to Section 232 tariffs, including wooden furniture and cabinetry. The province made up 13 per cent of Canada’s exports to the U.S. in those categories. That was higher than Ontario, at 11 per cent, but well below British Columbia at 46 per cent.

To conduct its analysis, The Logic compiled a list of products subject to Section 232 tariffs, according to codes used by U.S. Customs and Border Protection, which are mostly harmonized with Canadian tariff codes. The Logic then examined export data from Statistics Canada for those specific product categories from 2020 to 2024, broken down by province and territory.

At a Toronto trade event in October, Smith acknowledged Ontario’s greater exposure to Trump’s tariffs, comparing her circumstances to those of Ford. “Doug has a very different set of difficulties that he’s facing, and I’m very, very mindful of that, because he’s hit by steel and aluminum and autos and softwood lumber,” she said.

Alberta’s current situation, however, isn’t a result of pure luck, Smith argued. “Part of the reason for that, I think, is that we’re selling products that the Americans want, and we’ve made the case.”

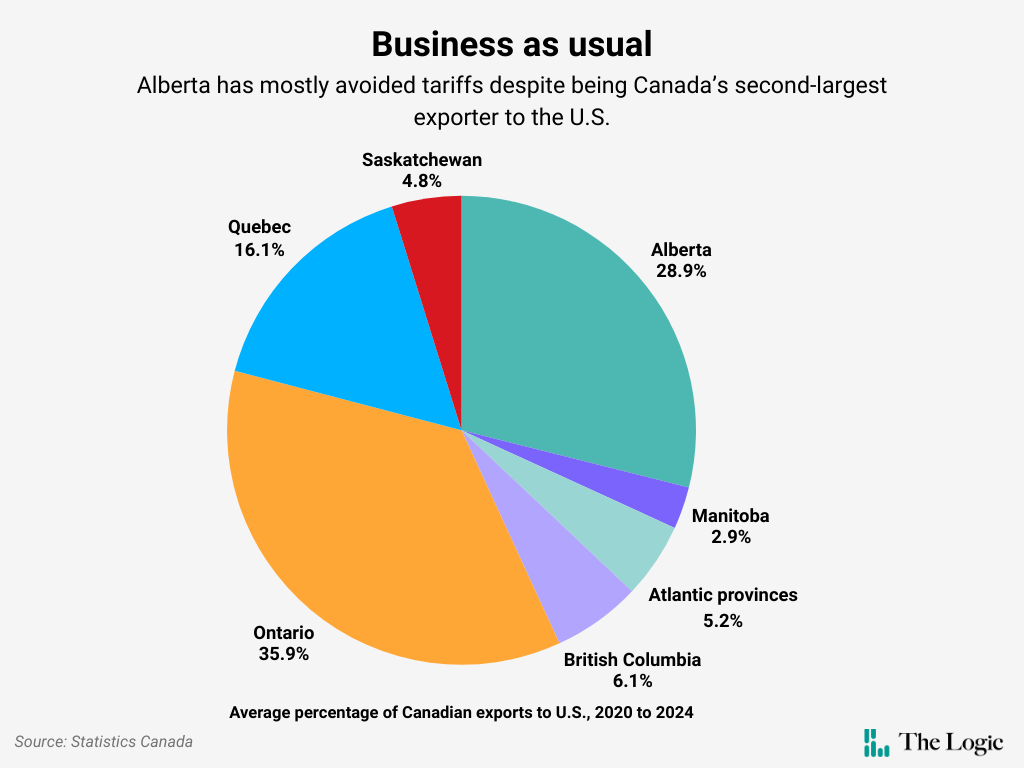

While oil and gas exports to the U.S. have insulated Alberta from the trade war, its reliance on that business also means its economy is the most exposed of any province—at least potentially. In 2023, Alberta’s merchandise exports to the U.S. accounted for 34 per cent of its total GDP, much higher than Ontario’s 18 per cent or Quebec’s 15 per cent, according to RBC research. From 2020 through 2024, Alberta made up an average of 29 per cent of Canada’s annual exports to the U.S., second only to Ontario’s 36 per cent.

Energy exports make up the lion’s share of the total. Alberta exported $121 billion worth of crude oil to the U.S. in 2024, about 75 per cent of the $162 billion worth of total goods it sold to the country.

Taylor MacPherson, an energy expert at the Montreal Economic Institute, said the U.S. refrained from leveling tariffs on Canadian oil and gas due to the deep integration of North America’s energy systems. The U.S. has purchased Canada’s fossil fuels for more than 100 years, he said, and today the country’s refineries are heavily dependent on Canadian oil.

Those facilities are calibrated to accept Canada’s uniquely heavy oilsands blends, while the Canadian industry’s cost-cutting efforts, combined with a lack of pipeline capacity to non-U.S. markets, have kept Canadian crude relatively cheap. Perhaps more importantly to Trump, MacPherson said, tariffs on Canadian oil would raise the prices Americans pay at the gas pump.

“It effectively becomes taxing U.S. refineries and taxing U.S. drivers, and that’s political suicide,” he said.

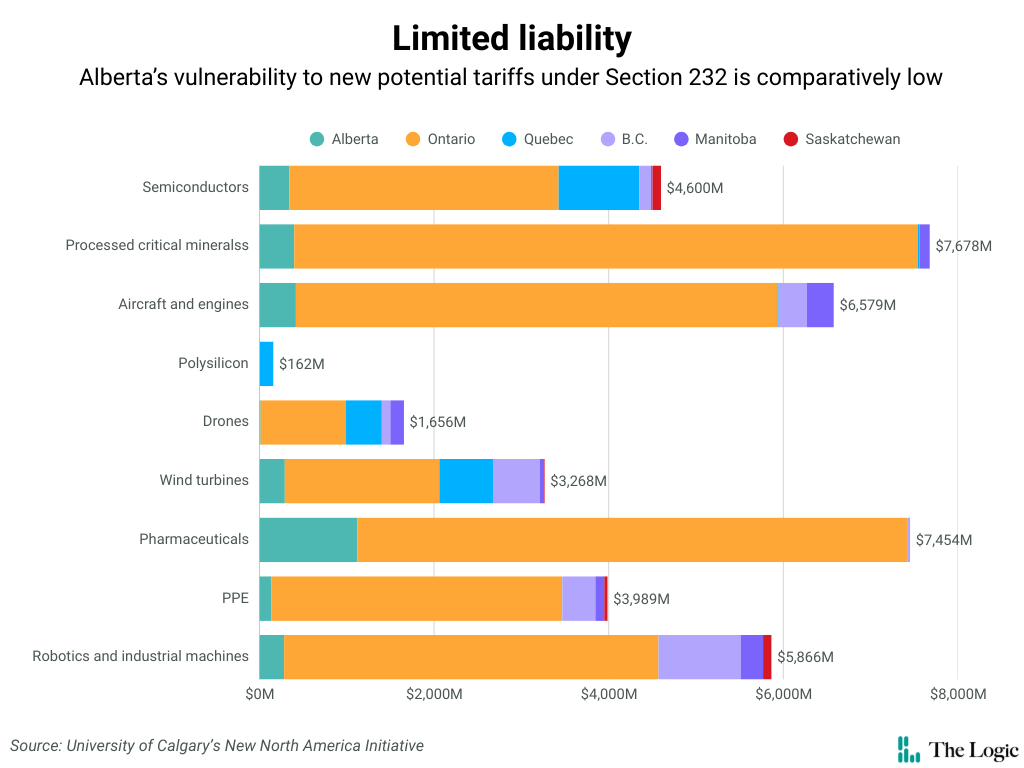

For now, Alberta’s privileged position appears secure. This past fall, a team of researchers with the New North America Initiative at the School of Public Policy at the University of Calgary conducted a similar analysis of the goods currently facing Section 232 investigations—probes the U.S. administration could use as the basis of new tariffs in the future.

That analysis also showed that, even if Trump imposes import duties on pharmaceuticals, processed critical minerals, semiconductors, aircraft, wind turbines, drones, polysilicon, robotics or personal protective equipment, Alberta would remain relatively unaffected.

Carlo Dade, director of international policy at the school, said this could let Alberta direct resources toward “the fewer areas that will be heavily impacted”—work he said it can start doing as soon as Trump launches a Section 232 probe. Because, however secure its future looks now, Dade said, the province is in no position to take its circumstances for granted. “We’re in an era of unprecedented,” he said. “It means that Alberta can’t be complacent.”