Kim Jin-ai, chief commissioner of Presidential Commission on Architecture Policy, discusses her latest book and what makes Seoul attractive

This is one of a series of interviews in which Kim Hoo-ran, editor-at-large at The Korea Herald, speaks with leaders, trailblazers, unsung heroes and both well-known and lesser-known figures who share the stories of their lives and their visions for a better world — Ed.

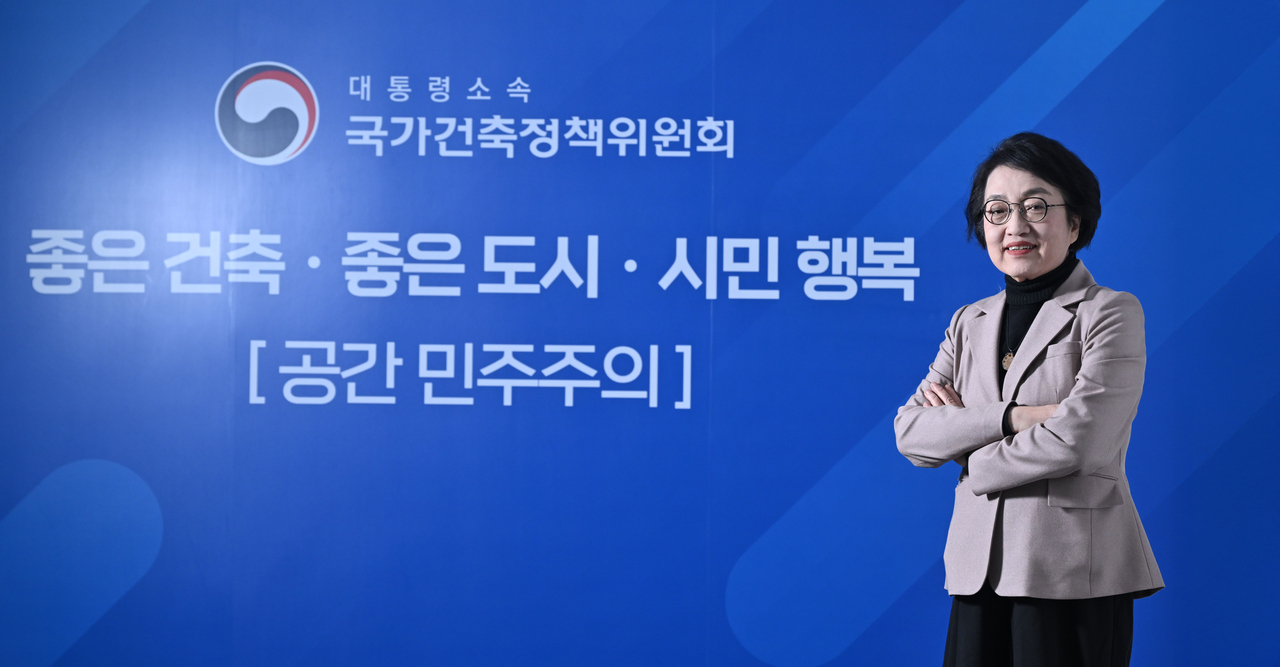

Kim Jin-ai, chief commissioner of the Presidential Commission on Architecture Policy, speaks during an interview with The Korea Herald at her office in downtown Seoul, Dec. 22. (Im Se-jun/The Korea Herald)

Kim Jin-ai, chief commissioner of the Presidential Commission on Architecture Policy, speaks during an interview with The Korea Herald at her office in downtown Seoul, Dec. 22. (Im Se-jun/The Korea Herald) She is an Energizer Bunny, filling the room with life. I pose a question, and she volleys back a response without pause. Her rapid-fire speech and adamantly spoken words convey confidence.

Writing is her way of “releasing pent-up energy and to detox,” says Kim Jin-ai, chief commissioner of the Presidential Commission on Architecture Policy, during an interview with The Korea Herald at her office in downtown Seoul, Dec. 22.

It is hardly surprising that the architect and urban planner has authored some 30 books in the past three decades, given the level of her energy.

A self-described “typical morning person,” she wakes up at four or five in the morning and writes for about 2-3 hours.

“I get up at dawn to really see myself and to write. These writings, when they accumulate, become a book,” she explains.

The latest result of those writings is “So__Seoul” (unofficial translation), published by Changbi Publishers last month. The book traces Seoul’s growth, interweaving the story of Kim’s own growth and the various neighborhoods she called home from childhood to the present day.

The scene that changed Seoul forever was the 2002 World Cup, according to Kim. Co-hosted by Korea and Japan, the monthlong event saw tens of thousands of people take to the streets to cheer on the football teams.

“I realized for the first time that a square could be a space of joy,” she says. “That is when Seoul finally changed and has continued to change ever since,” she notes.

“Seoul is on the rise as a global city and the time is ripe for the emergence of ‘Seouler,’ just as there is Londoner and Parisian,” she says.

Kim picks Seoul’s tall mountains and its wide river as the capital’s biggest assets. Next is the public transportation system.

“Really, there’s nothing comparable,” she says.

She claims safety as another strong asset while conceding that there are people who think it could be made safer.

To her list of Seoul’s assets, she adds the omnipresent delivery services, the city’s energy and the feeling of being taken care of.

A view of the Han River with Mt. Nam in the center background (“So__Seoul,” courtesy of Changbi Publishers)

A view of the Han River with Mt. Nam in the center background (“So__Seoul,” courtesy of Changbi Publishers) As for the capital’s shortcomings, she points to excessive installations and structures in public spaces, noting that public squares could be used better. The chaos of small alleys where pedestrians, cars, motorcycles, bicycles and kickboards all share the same road also requires attention.

Seoul is attractive because it is full of contradictions, Kim says, just as a person full of surprises is alluring. “You come expecting to see Gangnam style and when you visit the old part of the city, it is completely different,” she says, referring to Psy’s global hit “Gangnam Style.”

Kim dismisses the notion of an ideal city, “But, there is the best city,” she adds.

“The best city is the one you are living in. … Unless you live in a war-torn city or a city that is rife with violence, I think you should think of your city as the best city and work to make it the best city.”

Though Kim characterizes Seoul as a very good place to live, calling it a beautiful and very “spicy” city, she is quick to point out its other problems.

“There is cutthroat competition, survival of the fittest and polarization,” she says.

Seoul is an expensive city, one that is driving away young people.

“I think the biggest problem is the decline in the young population. The only reason for this is the exorbitant housing price,” she notes.

Still, she is hopeful: She sees many more things in Seoul’s favor and believes that the problems can be fixed.

Things are improving, she notes, citing the example of housing supply.

“When the new planned cities were being built with apartments going up in frenzied construction 30 years ago, the rate of housing supply per family was 45-50 percent in Seoul and 60-70 percent in the provinces,” she recalls.

“Today, that housing supply per family ratio in Seoul stands at 94 percent. In the provincial cities, that figure stands between 105 percent and 110 percent,” she says.

“Things have become better. The problem now is not hunger but hunger for more driven by envy,” she says.

Kim stresses the importance of community in tackling challenges such as the declining population, low birth rate, aging society and climate change.

Kim urges that strengthening neighborhoods is an imperative. “Of course, internationalization and globalization are important. But above all else, communities that function healthily are crucial,” she says.

“That is why I am even more concerned about polarization. Jobs must be more spread out. Jobs are now concentrated in the four CBDs: the old downtown, Gangnam, Yeongdeungpo and Yeouido.”

Is this something that her commission can address?

“Of course, there are many things that can be achieved through architecture. But, there is also much that cannot be achieved through architecture,” she says.

Kim’s work at the Presidential Commission on Architecture Policy involves “planning a ‘housing revolution.’”

“I am pushing the notion that a revolution in urban architecture, instead of even more high-rise-centric urban redevelopment, is necessary to solve many of Seoul’s problems.”

Appointed to head the commission last September, Kim points out that Korea is the only country in the world that has a presidential commission on architecture.

“Most of the work is not directly related to the public, but I intend to make it so,” she says.

Indeed, in her inauguration speech, Kim promised to strengthen communication with the public.

She came up with the slogan “Space Democracy” to encapsulate the commission’s goal.

People lack agency when it comes to space, Kim observes. “We tend to leave matters in the hands of the government when it comes to public spaces, while private spaces are left to the whims of the marketplace.”

The presidential motorcade heads toward Cheong Wa Dae , Dec. 29, marking the return of the presidential office to Cheong Wa Dae after three years and seven months. (Pooled photo via Yonhap)

The presidential motorcade heads toward Cheong Wa Dae , Dec. 29, marking the return of the presidential office to Cheong Wa Dae after three years and seven months. (Pooled photo via Yonhap) “The highest level of space democracy, I think, is authenticity,” Kim says. She cites the example of Cheong Wa Dae, the presidential compound also known as the Blue House.

Impeached President Yoon Suk Yeol abandoned the presidential office in favor of the Ministry of National Defense building in Yongsan-gu. President Lee Jae Myung, who took office in June, began working at Cheong Wa Dae on Dec. 29, restoring Cheong Wa Dae to its former status.

“That space had authenticity as a symbol of the Republic of Korea and became a brand,” she points out. “I cannot forgive the relocation of the presidential office. It was a violation of space democracy,” she says, her voice rising. The return to Cheong Wa Dae marks the recovery of space democracy and, thereby, our authenticity, Kim notes.

“Such authenticity is not created by beauty alone. There is time that has elapsed in that space and it holds a meaning that we have attributed to it. The meaning of the space is shared by a great many people and the people are attached to it. Only then is something authentic,” she explains.

Taking issue with Seoul City’s hotly debated redevelopment plan for an area close to Jongmyo, Kim claims that the current plan will damage the authenticity of the Joseon-era royal shrine, which is a UNESCO-listed cultural heritage.

Seoul, with its more than 600 years of history, faces conservation and development pressures, especially in the older parts of the city, where you are likely to unearth artifacts anywhere you dig.

“This is not a matter of choice. There should be a compromise. Also, our design technology has improved. And people’s tastes and preferences have become more sophisticated,” she says.

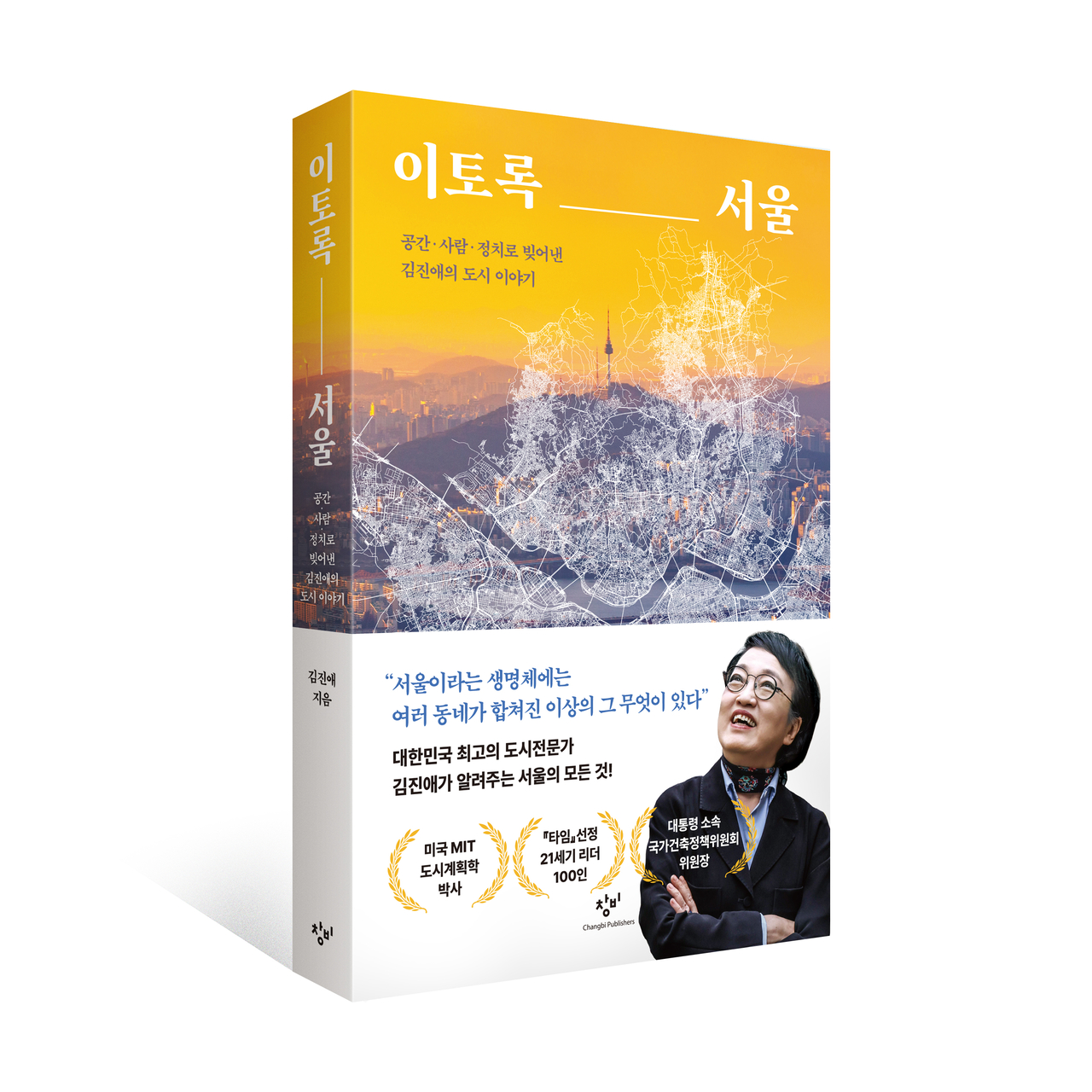

“So__Seoul” (unofficial translation) written by Kim Ji-ai and published by Changbi Publishers (Courtesy of Changbi Publishers)

“So__Seoul” (unofficial translation) written by Kim Ji-ai and published by Changbi Publishers (Courtesy of Changbi Publishers) Kim has left it up to the readers to fill in the blank in the title of her book, “So__Seoul.” In fact, Changbi Publishers has organized a contest inviting readers to fill in the blank.

What word would the author use to fill the blank?

“Me? It’s different each day,” she says with a laugh.

“A few days ago, I felt anxious for Seoul. Another day, the words ‘beating heart’ seemed right and yesterday, ‘tangy’ felt just right,” she says.

“Seoul is a city of numerous twists,” she says in explaining her choice of the word “tangy,” a taste that is both sharp and refreshing.

Born the third daughter in a family of 10 children in 1953, a few months before the end of the Korean War, Kim determined early on that she would earn her own living.

“That meant independence,” she says.

That desire to make a living was the sole reason for studying architecture at Seoul National University. She had heard that science and engineering people made a good living, and architecture seemed a good choice given her interest in the humanities and art.

She was the only woman in the department when she graduated.

At Massachusetts Institute of Technology, she chose to pursue urban planning for her doctorate, a decision influenced by Hannah Arendt’s “The Human Condition.” Captivated by the book that deals with human agency and political freedom, she adopted Arendt as her life mentor.

In Korea, the renewal of Insa-dong and the Sanbon New Town plan, a first-generation planned city, are some of the projects Kim took on.

Moving from architecture to urban planning, Kim expanded her world even more when she entered politics in 2004 by running for Yongsan mayor.

“Urban planning is closely tied to politics and when you work on cities, there will come a time when you start thinking, ‘It might be better if I did it myself,” she says of her motivation for entering politics.

“I think the foremost definition of politics is hope for change. Through politics, you can hope for change,” she explains.

In 2009 and 2020 she took proportional representative seats at the National Assembly on the Democrat Party ticket. As a legislator, she was known for her feistiness and no-nonsense attitude. In March 2021, she ran in the Seoul mayoral by-election, resigning from her parliamentary seat.

Of her achievements as a politician, she is most proud of the Framework Act on Architecture that went into effect in 2008.

“This law could not have been possible without the collaboration between President Roh Moo-hyun and me. The law created the Presidential Commission on Architecture Policy, and now, 18 years later, I am in charge of the organization,” she says.

“It would be great if, together with the president, we could achieve a revolution in housing architecture,” she says.

Will she run for Seoul mayor again? Given that her book ends with a no-holds-barred review of Seoul mayors past and present and the timing of the book’s release ahead of the June general election, it is a fair question to ask.

“The book has nothing to do with it. I wanted candidates to read it and learn more about Seoul,” she says.

“As for running, I think I will make a decision within a month.”

Kim Jin-ai, chief commissioner of the Presidential Commission on Architecture Policy, poses for a photo during an interview with The Korea Herald, Dec. 22 (Im Se-jun/The Korea Herald)

Kim Jin-ai, chief commissioner of the Presidential Commission on Architecture Policy, poses for a photo during an interview with The Korea Herald, Dec. 22 (Im Se-jun/The Korea Herald) khooran@heraldcorp.com