Key Points and Summary – In December 2025, the USS Abraham Lincoln aircraft carrier strike group deployed to the Indo-Pacific, arriving in Guam on December 12 before patrolling the Philippine and South China Seas.

-This mission aims to maintain open shipping lanes, reassure allies like Japan and the Philippines, and challenge China’s expansive maritime claims.

USS Abraham Lincoln. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

120118-N-QH883-003

INDIAN OCEAN, (Jan 18, 2012) The Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln (CVN 72) transits the Indian Ocean. Abraham Lincoln is in the U.S. 7th Fleet area of responsibility as part of a deployment to the western Pacific and Indian Oceans to support coalition efforts. (U.S. Navy photo by Chief Mass Communication Specialist Eric S. Powell/ Released)

-However, the carrier operates under the threat of China’s “carrier killer” arsenal, specifically the maneuverable DF-21D and the long-range DF-26 ballistic missiles, which can target U.S. naval assets as far away as Guam.

USS Abraham Lincoln ‘Deployed’: Navy Aircraft Carrier ‘Challenges’ China in ‘High-Stakes’ South China Sea ‘Patrol’

In December of 2025, the aircraft carrier Abraham Lincoln and her strike group were spotted in the Indo-Pacific.

The ship arrived in Guam on December 12, then headed toward the Philippine Sea and is expected to patrol the South China Sea before eventually returning to its home port in San Diego.

Other U.S. naval ships, such as the amphibious assault ship USS Tripoli (LHA-7) and the fast-attack submarine USS Seawolf (SSN-21), are operating in the Indo-Pacific to maintain a significant American presence in the region.

This is part of a larger routine patrol in the area to keep shipping lanes and monitor China.

The South China Sea

The South China Sea occupies a unique position in global geopolitics.

It is one of the world’s most heavily trafficked maritime corridors, carrying trillions of dollars in trade annually and serving as a lifeline for energy shipments bound for East and Southeast Asia.

Multiple regional claimants, including China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, and Taiwan, also contest the sea. China’s claim, represented by the so-called nine-dash line, covers most of the basin and overlaps with the internationally recognized exclusive economic zones of other coastal states.

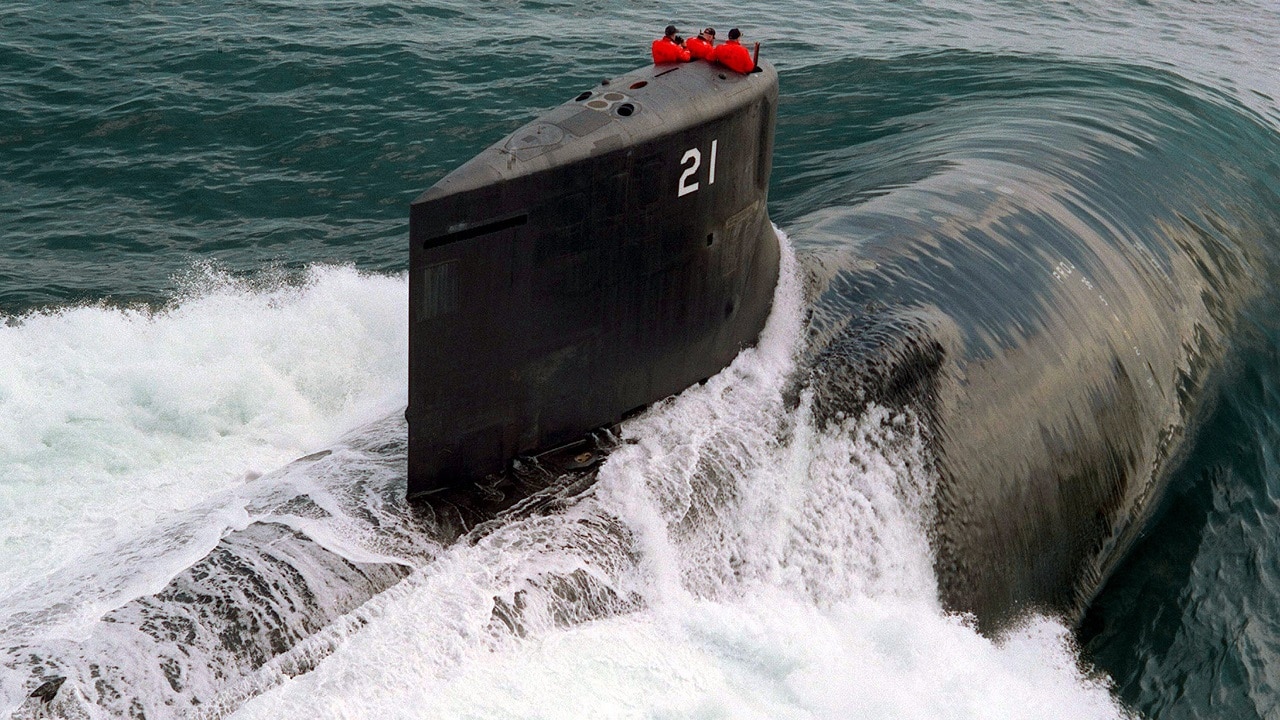

Seawolf-Class Submarine. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

PUGET SOUND, Wash. (Sept. 11, 2017) The Seawolf-class fast-attack submarine USS Jimmy Carter (SSN 23) transits the Hood Canal as the boat returns home to Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor. Jimmy Carter is the last and most advanced of the Seawolf-class attack submarines, which are all homeported at Naval Base Kitsap. (U.S. Navy photo by Lt. Cmdr. Michael Smith/Released)

The U.S. Navy’s newest attack submarine, USS Seawolf (SSN 21), conducts Bravo sea trials off the coast of Connecticut in preparation for its scheduled commissioning in July 1997.

The Seawolf-class fast-attack submarine USS Connecticut transits the Pacific Ocean during Annual Exercise. ANNUALEX is a yearly bilateral exercise with the U.S. Navy and the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force.

The United States takes no official position on which country should control specific features in the South China Sea. Still, it does explicitly reject claims that contradict international maritime law, particularly the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

From Washington’s perspective, China’s expansive assertions, combined with its construction of artificial islands and installation of military infrastructure, threaten to undermine freedom of navigation and set dangerous precedents for maritime governance.

It is in this environment that USS Abraham Lincoln operates. When a U.S. aircraft carrier enters waters near the South China Sea or conducts flight operations in adjacent seas such as the Philippine Sea, it signals that these spaces are not closed military zones subject to the unilateral control of any one state.

Even when carriers do not conduct formal freedom-of-navigation transits themselves, their presence underwrites such operations by smaller surface combatants and aircraft.

A carrier strike group brings airborne surveillance, air superiority, electronic warfare, and rapid-strike capabilities that reinforce the credibility of U.S. assertions regarding international access.

In practical terms, this means that China cannot assume that enhanced missile coverage or island-based airfields will deter American maritime activity by default.

Sending a Strong Message

Deterrence is another central reason for Abraham Lincoln’s deployment.

In a region where U.S. allies are geographically close to China and politically sensitive to escalation, the carrier’s independence is crucial. It allows the United States to maintain combat power even if access to land bases is constrained during a crisis.

Whether the scenario involves tensions over Taiwan, confrontations between Chinese and Philippine forces, or broader regional instability, a forward-deployed carrier ensures that the United States has immediate response options. Deterrence, in this context, is about convincing potential adversaries that aggression would be costly, uncertain, and unlikely to succeed.

Of course, Abraham Lincoln isn’t there solely to deter China; it is also there to reassure its allies in the region. Countries such as Japan, the Philippines, and Australia closely watch U.S. deployment patterns as indicators of American commitment.

In Southeast Asia, especially, many governments seek a balance between economic engagement with China and security alignment with the United States.

The physical presence of carriers like USS Abraham Lincoln provides tangible evidence that Washington is willing to expend resources and accept risk in defense of a free and open Indo-Pacific.

Joint exercises, port visits, and coordinated patrols conducted around a carrier strike group deepen interoperability among allied forces and signal to Beijing that coercive actions against smaller states will not occur in a vacuum.

China’s Anti-Ship Arsenal

China keeps a close watch on American assets in its “backyard.” Should things heat up, it has several tools in its arsenal to deal with American carriers.

Among these, the DF-21D occupies a special place. Often referred to as the world’s first operational anti-ship ballistic missile, the DF-21D was developed to strike moving naval targets at ranges exceeding 1,500 kilometers. Unlike traditional cruise missiles, it follows a ballistic trajectory before using a maneuverable reentry vehicle to adjust course during its terminal phase.

This design complicates interception and challenges long-standing assumptions about the survivability of carriers operating within the First Island Chain.

While questions remain about the real-world effectiveness of the sensor and command networks required to guide such a weapon, U.S. planners treat the DF-21D as a credible threat that must be countered rather than dismissed.

The DF-26 extends this threat even further. With a reported range of more than 4,000 kilometers, it allows China to hold at risk naval forces operating far from the Chinese coast, including areas once considered relatively safe for carrier maneuver.

The DF-26 is especially threatening, as it can target assets as far back as Guam, including naval targets and hardened targets on the base. Its dual-capable nature, meaning it can carry either conventional or nuclear warheads, introduces additional complexity.

In a conflict scenario, differentiating between nuclear and non-nuclear launches would be extremely difficult, raising the risk of rapid escalation.

About the Author: Isaac Seitz

Isaac Seitz, a Defense Columnist, graduated from Patrick Henry College’s Strategic Intelligence and National Security program. He has also studied Russian at Middlebury Language Schools and has worked as an intelligence Analyst in the private sector.