“You start reading the stories about them and the sorts of myths and legends of people who come across them …. [wallabies are] the classic kind of local escapees made good in the environment they’ve escaped into,” Archer said.

The red-necked wallaby earned its name for its distinctive patch of rust-coloured fur. Credit: Sue Corrin

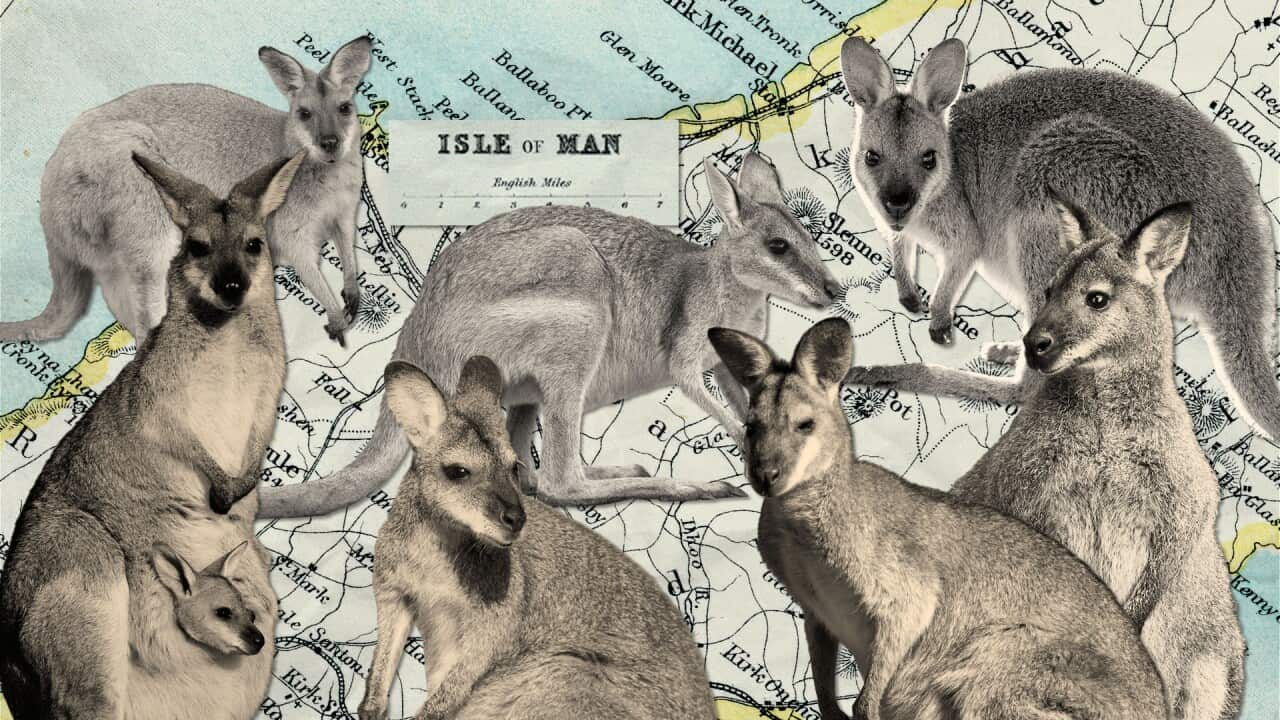

In 2023, drone surveys by Manx Wildlife Trust identified 568 feral wallabies in Ballaugh Curragh, a protected marshland area on the Isle of Man.

“I do wonder if there was quite a bit missed previously, because otherwise we’re talking about a massive population increase in a very short period of time.”

Wallabies on the run

It is known that in 1965, a wallaby named Wanda escaped from Curraghs Wildlife Park during its first year of operation. She was returned to the government-owned zoo within a year, but in the decade that followed, more wallabies escaped from their enclosures, according to local media.

Today, there are more than 100 species at Curraghs Wildlife Park, including red pandas, penguins and a population of Australian wallabies. Credit: Curraghs Wildlife Park

The exact number of escapees is unconfirmed, although the gene pool within the population is likely narrow.

Archer believes crop damage and the risks associated with inbreeding are key concerns for farmers.

Simon Archer said one of the best-preserved medieval castles in Europe is right on his doorstep. Credit: Simon Archer

“There is a danger that you’re going to have quite ill wallabies wandering around the place … and farmers with livestock understand what that can mean for their animals in the future,” Archer said.

‘Quite damaging’

The wetlands are known for their bog pools, birch scrub and grey willow — called “curragh” by locals, from which the area takes its name. With mild winters and cool summers, the habitat also resembles parts of Tasmania, which is where the red-necked wallaby originates.

What to do?

“I think we need to close these kinds of knowledge gaps, answer the questions that we have, before we make a statement either way,” he said.

Feral Australian species elsewhere

“It’s so difficult to put genies back in bottles. With globalisation, people buying things overseas, going overseas a few times a year, it’s [biosecurity threats are] just exploding,” he said.

Detector dog teams intercepted more than 42,000 high-risk items, including at Australian airports in 2024. Source: AAP / David Jones

The Department of Defence has a budget of almost $60 billion a year. Comparatively, funding for biosecurity is $935 million, which is expected to decline to $889 million in 2028–2029, according to the Australian Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry.

“I mean, it’s not a sexy issue,” he said.