Nato’s silence in response to Donald Trump’s threats to seize Greenland has prompted alarm among European capitals fearful that the alliance is failing to defend the rights of Denmark.

It has not issued a public statement asserting Denmark and Greenland’s territorial integrity and sovereignty, or responded to the US president’s stated ambition for the vast Arctic island that is part of the kingdom of Denmark.

That has raised the ire of European members trying to present a united front and ease transatlantic tensions, and stands in stark contrast to the EU’s recent efforts to rally around Copenhagen.

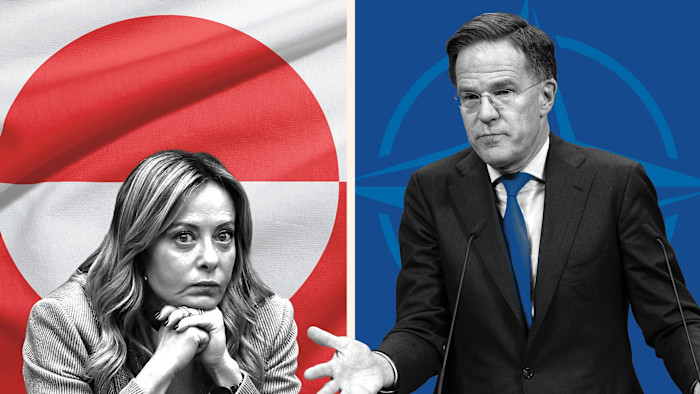

Mark Rutte, the alliance’s secretary-general who enjoys a warm relationship with Trump, has been unusually absent on such a critical security issue affecting his membership. Suggestions from Paris and other capitals for enhanced Nato activity in Greenland have not yet been taken up.

While European officials accept that the US’s central role in the military alliance limits its options to respond, many told the FT that its absence from the crisis risks enhancing the sense of Trump’s impunity in dealing with allies and exploiting Europe’s security dependency on Washington.

“Since we’re clearly talking about nations that are all Nato allies, Nato should initiate a serious debate on this . . . in order to reduce or ease the pressure on the issue,” said Giorgia Meloni, Italy’s prime minister. “The debate is a debate that must involve Nato.”

Trump has accused Denmark of failing to adequately protect the island and invest in its security despite what he claims is rising Russian and Chinese naval activity around it. The White House has said military action was “an option” alongside purchase or other methods of taking control.

That has posed an excruciating challenge for Nato and Rutte. A US invasion or annexation attempt would mean direct conflict between two allies, calling into question its Article 5 mutual defence clause that many members see as its raison d’être.

“They’re conspicuously silent,” said one EU official. “Rutte was supposed to be the man Europe could rely on to be our Trump-whisperer. But he wasn’t supposed to be this quiet.”

“Of course, it is difficult to discuss these things inside Nato,” said an alliance diplomat. “But if you don’t, it implies that we are all OK with what is going on.”

The alliance has issued no public remarks, and Rutte, typically omnipresent in discussions about Euro-Atlantic security, has given only a 60-second response to a television interviewer’s question regarding the crisis.

“While we’re not going to disclose details of diplomatic discussions, the secretary-general is working closely with leaders and senior officials on both sides of the Atlantic, as he always does,” Nato spokesperson Allison Hart told the FT.

A Danish navy vessel patrols the waters off Nuuk, Greenland’s capital © Odd Andersen/AFP/Getty Images

A Danish navy vessel patrols the waters off Nuuk, Greenland’s capital © Odd Andersen/AFP/Getty Images

For much of last year, Copenhagen took a low-profile approach to the Greenland issue, eschewing public remarks in response to inflammatory statements from Trump or his administration, and urging EU and Nato allies to do the same.

But that tactic was abandoned this week. Mette Frederiksen, Denmark’s prime minister, said that Trump was “serious” about taking Greenland, and that “if the US chooses to attack another Nato country militarily, everything stops. Including our Nato.”

European officials involved in negotiations in Brussels said the statement was influenced by Copenhagen’s rising irritation at Nato’s silence, and reflected a desire to ensure the alliance realised what was at stake.

Danish lawmakers have called for Nato to play a stronger role in the dispute with the US. Carsten Bach, a Liberal Alliance MP, called for a discussion under Article 4 of Nato’s treaty, which refers to threats against member states.

“There is one country in Nato, the US, that sees a threat in the Arctic that may not be quite so clear to the rest of us, and therefore I believe that Nato should play a significant role in this conflict that has now arisen between two Nato countries,” he added.

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen this week said that “law is stronger than force” in reference to Greenland, while Council President António Costa said: “Nothing can be decided about Denmark and about Greenland without Denmark, or without Greenland.”

The leaders of Nato allies France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain and the UK released a joint statement with Denmark noting that they “will not stop defending” the principles of “sovereignty, territorial integrity and the inviolability of borders”.

Nato officials and member state diplomats posted to the alliance say that there is private diplomacy ongoing and internal work to boost collective security in the Arctic region around Greenland. The past couple of years have seen a significant shift from Nato states in that region supporting more alliance leadership, the officials add.

“We have Baltic Sentry, why not have Greenland Sentry? That is what we can do,” said EU defence commissioner Andrius Kubilius, referring to a Nato mission launched a year ago to better protect critical infrastructure in the Baltic Sea.

“I don’t know about those discussions inside of Nato [about Greenland], and how they are happening. But just looking from the outside, Nato is in some kind of special situation,” Kubilius added, citing the fact that both Denmark and the US are members.

“Ukraine is easy for us. Russia has long been the enemy. Greenland is much more complicated. The US is meant to be our great ally. That just makes everything so much more difficult,” said a senior Nordic diplomat.

Recommended

Asked directly about Trump’s threats this week, Rutte told CNN that he agreed with the US president’s assessment about increased Russian and Chinese activities in the region, and the need to boost security.

“Look at Denmark, they are investing heavily in their military,” he said. “And the Danes are totally fine if the US would have a bigger presence [in Greenland] than they have now. So I think this collectively shows that . . . we have to make sure that the Arctic stays safe.”

Additional reporting by Amy Kazmin in Rome and Andy Bounds in Brussels