Venezuela oil now appears a hot potato. A number of developments are moving around the Venezuela crude that pulled the Empire to take military action against the Bolivarian republic. The crude is not like grab and take home.

The U.S. President Donald Trump, in an executive order, has blocked creditors and courts from laying claim to the Venezuelan oil sales held in the U.S. Treasury accounts. The aim of this move is to, according to the White House, preserve the funds to “advance the U.S. foreign policy objectives” in the region – Latin America.

Earlier, Chris Wright, the U.S. Energy Secretary, said: The U.S. plans to sell Venezuelan oil indefinitely.

The U.S. President pushed the U.S. oil giants and their European oil-friends to invest USD100 billion in the oil wells of Venezuela. The investment money was proposed to “very rapidly rebuild” Venezuela’s oil industry.

But Mr. Darren Woods, chairman and CEO of Exxon, said: It is un-investable today. Commercial framework, the legal system, security measures, etc. in Venezuela need “significant changes.” Mr. Woods, non-committal to the investment proposal, informed that a technical team from Exxon would visit Venezuela shortly for assessing the situation. He put his hope on joint working of the U.S. and the Venezuelan authorities.

Exxon had bitter experience twice in Venezuela. According to Mr. Woods, Exxon’s assets were seized twice in the Latin American country. That make Exxon cautious about re-entry in that country for a third time.

The U.S. President wants the oil giants to invest there and get their money back as quickly as possible. He is expecting a “tremendous success.” He wants speed in this Venezuela-venture. He assured the oil-lords total safety. Instead of deploying troops in Venezuela, the U.S. President told the oil company heads: Security guarantee would come from working with the Venezuelan leadership and the Venezuelan people. Moreover, the companies going to invest in Venezuela have to take, along with investment, some security.

Political leadership and people are, as it appears from the U.S. President’s suggestion, a major factor while considering the question of investment. However, who can assure these two – political leadership and people – would behave in a friendly way? Both of these two factors have a history different from wishes of the U.S. Chavismo-politics has made significant changes in these two areas.

If oil companies are to arrange some security arrangements, shall that mean deploying private military contractors? Deployment of private military contractors would give a “new” shape to the contradiction that would surface while the oil companies would go for grabbing the Venezuelan crude.

Mr. Mark Nelson, vice-chairman of Chevron, expects to increase oil flows from Venezuela by 50%. However, that would require two years.

Chevron is the only U.S. oil producer now operating in Venezuela in partnership with PDVSA, the state-owned Venezuelan oil enterprise. Analysts find: Chevron is the biggest winner in Venezuela now, as it is operating there and it has the required infrastructure.

Ryan Lance, chairman and CEO of ConocoPhillips, echoed the Exxon chief: Major reforms are required as the first step to make an investment in Venezuela. ConocoPhillips wants restructuring of the entire energy system in Venezuela.

ConocoPhillips is the largest creditor from Venezuela’s nationalization of natural resources.

The U.S. President wants the oil giants start with a “clean slate” and should not be reimbursed for write offs in the past. He agreed with the point raised by the oil company heads: “There are risks” in Venezuela.

But what shall happen to Conoco? Its past writes off amounts to USD12 billion.

To double Venezuela’s current oil production, it would require four more years – 2030, and an investment of USD110 billion.

Oil giants from Europe including Italy’s Eni and Spain’s Repsol expressed their willingness to invest more and increase production. These two companies are operating in Venezuela in joint ventures.

Halliburton and SLB also expressed willingness to invest more in Venezuela. The SLB is already a partner of Chevron’s operation in Venezuela.

These oil companies’ “willingness” in the January 9, 2026 meeting with the U.S. President sounds just like lending voices to the U.S. head of the state. But there is the question of increased competition the U.S. oil companies would face, as increase in Venezuela’s extra-heavy grade crude production would face a market with lower price. This means a lower profit. Consequently, what would be the real gain? A calculus is needed for the oil companies. But that calculus of investment and profit will not give actual result, as actual result also depends on state of politics in Venezuela in the coming months.

The most vital question related to this hydrocarbon investment plan is politics, which includes constitution. Venezuela’s constitution proclaims: The nation, that is people, owns all mineral and hydrocarbon deposits within its own territory including those beneath its seabed.

Bringing amendments in the constitution is a long process. It is also complex. In no way it is a Delta Force operation. There are political forces opposed to the politics Chavez initiated and Maduro was upholding with limitations. But that opposition is not that heavy to make a sweeping change, reformulate legal instruments to de-nationalize natural resources that the Venezuelan people own, in the constitution.

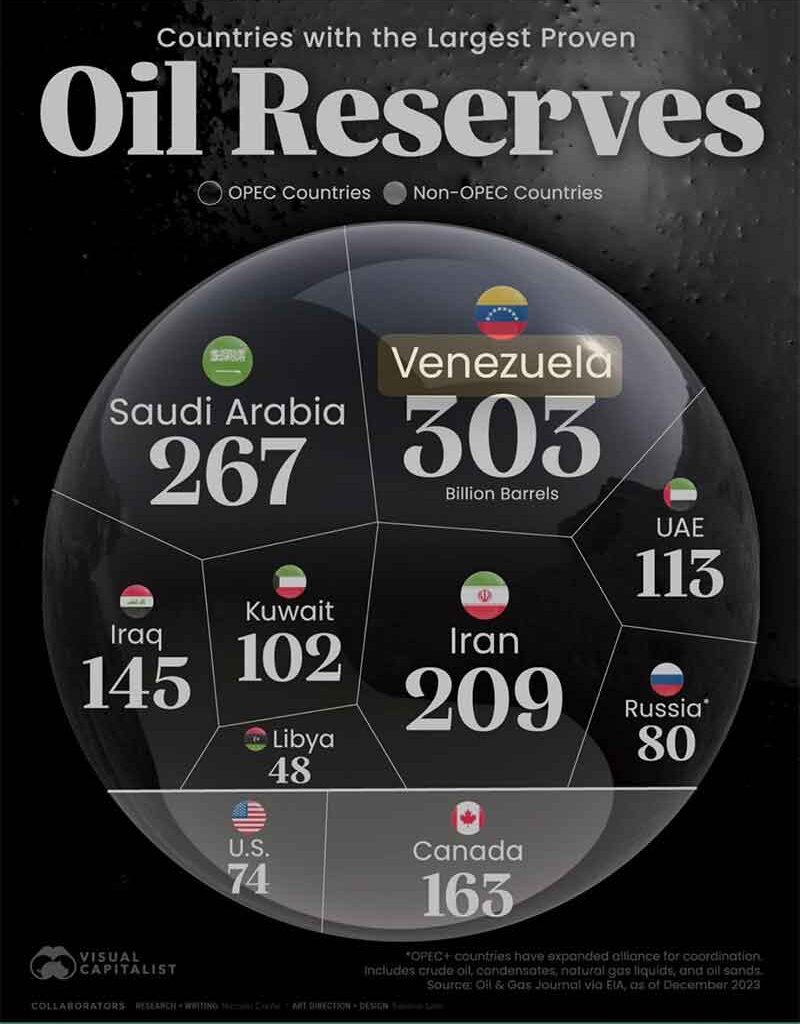

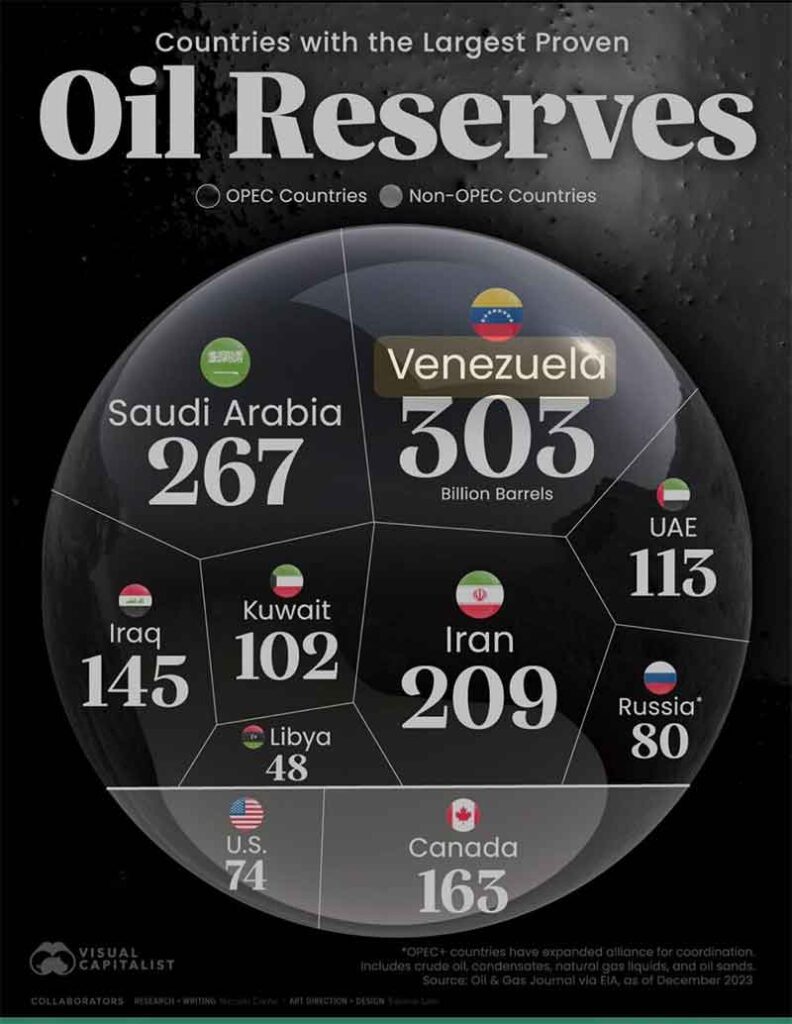

There is also another factor: China. The emerging power has already oil contracts with Venezuela, which are operating. These contracts were signed years ago. In the area of hydrocarbon, Venezuela owes about USD10 billion to China. This debt is being repaid by oil to China. Two state-owned Chinese companies are entitled to 4.4 billion barrels of oil reserve in Venezuela. For any foreign country, China’s share of oil in Venezuela is the biggest.

The U.S. has to deal with this issue – China’s stake in Venezuela. This is connected to other trade related issues between the U.S. and China, which the U.S. is trying to solve not with a heightened tone of confrontation.

This oil-picture in Venezuela has made the Venezuela crude a hot potato for the U.S.