At Texas A&M University, experimental particle physicist Dr. Rupak Mahapatra spends his days chasing some of the faintest signals in the universe. His lab designs cryogenic semiconductor detectors that listen for dark matter, a substance that makes up much of the cosmos but never shows itself in light.

Mahapatra and his collaborators also work with the international TESSERACT Collaboration, which builds detectors so sensitive they can notice energy changes smaller than a third of an electron volt. Their latest work, reported in Applied Physics Letters, now shows that the very silicon used to build these instruments can quietly sabotage that search.

Mahapatra compares today’s view of the universe to touching only one part of an elephant. “It’s like trying to describe an elephant by only touching its tail. We sense something massive and complex, but we’re only grasping a tiny part of it.” That missing part includes dark matter and dark energy, which together make up about 95 percent of everything that exists. Dark matter binds galaxies together, while dark energy pushes the universe to expand faster.

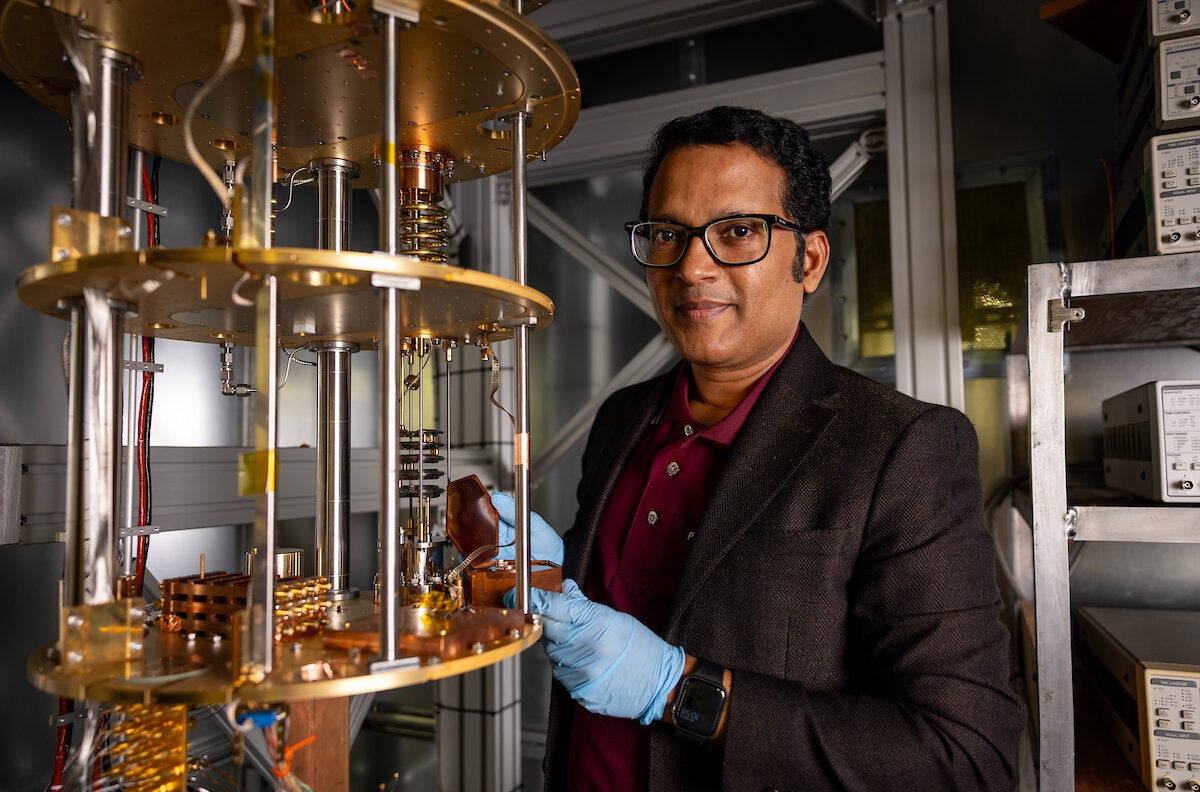

Dr. Rupak Mahapatra, an experimental particle physicist, holds a SuperCDMS detector. The highly sensitive devices, which are fabricated at Texas A&M University, are deepening the search for dark matter and have potential applications in quantum computing. (CREDIT: Laura McKenzie/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications)

Finding dark matter requires tools that can catch a particle that might interact once a year, or even once a decade. “The challenge is that dark matter interacts so weakly that we need detectors capable of seeing events that might happen once in a year, or even once in a decade,” Mahapatra said. Texas A&M is one of a few institutions helping to build and test TESSERACT, which uses silicon detectors chilled to near absolute zero to reduce outside noise.

How silicon detectors chase the invisible

“Each TESSERACT detector is a thin square of silicon fitted with tungsten transition edge sensors, known as TESs. These sensors sit at the edge of being superconducting, so even tiny energy shifts change their electrical behavior. Aluminum fins sit on top of the TESs and guide vibrations, called phonons, into the sensors. When a particle hits the silicon, it shakes the crystal, sending phonons into the aluminum and tungsten, where they get measured,” Mahapatra explained to The Brighter Side of News.

“To test the devices, our team fired pulses of blue laser light at them. Each photon carried 2.755 electron volts of energy. Most photons hit the silicon and spread their energy evenly across both sensor channels. Some struck the aluminum fins and lit up only one channel. These tests showed that a thin, 1 millimeter silicon detector reached a world leading energy resolution of 258.5 millielectron volts,” he continued.

The surprise came when the researchers compared two nearly identical detectors. One used 1 millimeter thick silicon, while the other used a 4 millimeter slab. Both ran in the same cryogenic system for 12 days. The thicker device produced about four times more false signals and background noise. That scaling showed the problem came from the bulk silicon, not the sensors on its surface.

A MINER detector that is used to search for low-energy neutrinos at the Texas A&M TRIGA reactor. This sapphire detector can be used for both dark matter searches and for detection of reactor neutrinos that can not only provide evidence of new physics but also enable nuclear non-proliferation. (CREDIT: Laura McKenzie/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications) A storm of vibrations inside the crystal

Even when no particles were present, both detectors recorded excess fluctuations that theory could not explain. Much of that noise appeared in both channels at once, which meant it affected the whole silicon chip. By modeling the data, the team found that this noise looked like a steady rain of tiny phonon bursts, each carrying about 0.68 millielectron volts of energy.

That energy matches the superconducting gap of aluminum. These phonons can break apart the paired electrons in the aluminum fins, creating real electrical signals that mimic particle hits. Over time, both the noise level and the power needed to keep the sensors working fell together. This showed that some hidden energy source inside the silicon was slowly fading.

The decay followed a power law, with an exponent near 0.635. That pattern suggests defects inside the crystal stored energy when the detector was at room temperature. Once cooled, those defects slowly relaxed, releasing their energy as phonon bursts over many days.

False events that look real

Above the noise floor, the detectors also saw real background events, known as the low energy excess. Some events landed in one channel and came from the metal films. Others shared their energy between both channels, which matched how laser photons behave in the silicon. These shared events also scaled with thickness, so the thicker detector produced about four times more of them per unit mass.

A wafer with many different designs of chips for the TESSERACT project. (CREDIT: Laura McKenzie/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications)

At low energies, the rate of these shared events dropped with time, just like the phonon noise. At higher energies, the rate stayed steadier, which fit with the idea that larger bursts are rarer. Together, the data pointed to defects inside the silicon as the source of both the noise and the false events.

This matters for more than dark matter searches. Superconducting qubits in quantum computers also rely on clean silicon. Stray phonons can break Cooper pairs and create quasiparticles that ruin quantum coherence. The study found that silicon phonon bursts can create quasiparticle densities that match what engineers already see in today’s qubits.

Why the material itself now matters

Mahapatra’s earlier work with the SuperCDMS experiment showed how new detection methods could open fresh windows on dark matter. In 2014, his team helped introduce voltage assisted calorimetric ionization detection, which let scientists probe lighter dark matter candidates. In 2022, he co authored a study showing why direct detection, indirect searches and collider experiments must work together. “No single experiment will give us all the answers,” Mahapatra notes. “We need synergy between different methods to piece together the full picture.”

The new findings add another layer. Even perfect shielding cannot stop phonons that start inside the detector itself. Silicon defects, dislocations, or past radiation damage can all trap energy that later escapes as vibrations. Until researchers learn how to control those defects, silicon will remain a quiet but stubborn source of false signals.

Graduate students, from left, Keith Hunter, Bailey Pickard and Mahdi Mirzakhani mounting detectors. (CREDIT: Laura McKenzie/Texas A&M University Division of Marketing and Communications) Practical Implications of the Research

These results change how scientists think about building the next generation of dark matter detectors and quantum computers. By showing that silicon defects create their own background noise, the study points to a new design challenge.

Future chips may need new ways of being grown, stored, and cooled so that trapped energy does not build up. For dark matter experiments, reducing this hidden noise could allow detectors to see even rarer particle events.

For quantum computing, fewer stray phonons could mean longer lasting qubits and more stable machines. In both fields, understanding the material at a deeper level may unlock better performance and new discoveries.

Related Stories