In a room of new computers and digital printers at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, several cubic feet of space are taken up by what, at first glance, appears to be an office copier. That’s not quite right, however. The bulky gray machine is a risograph.

Vicky Tomayko loads a fluorescent pink ink drum into the risograph machine. (Photos by Antonia DaSilva)

Vicky Tomayko loads a fluorescent pink ink drum into the risograph machine. (Photos by Antonia DaSilva)

The risograph was invented in Japan by Noboru Hayama. First released in 1980, they were originally intended for offices and schools. Much like a copy machine, they can produce multiples very quickly — more than 100 copies per minute.

While risographs have been replaced by laser and digital photocopiers in many contexts — including at the Work Center — in recent years there has been a resurgence of interest in them as a tool for artists.

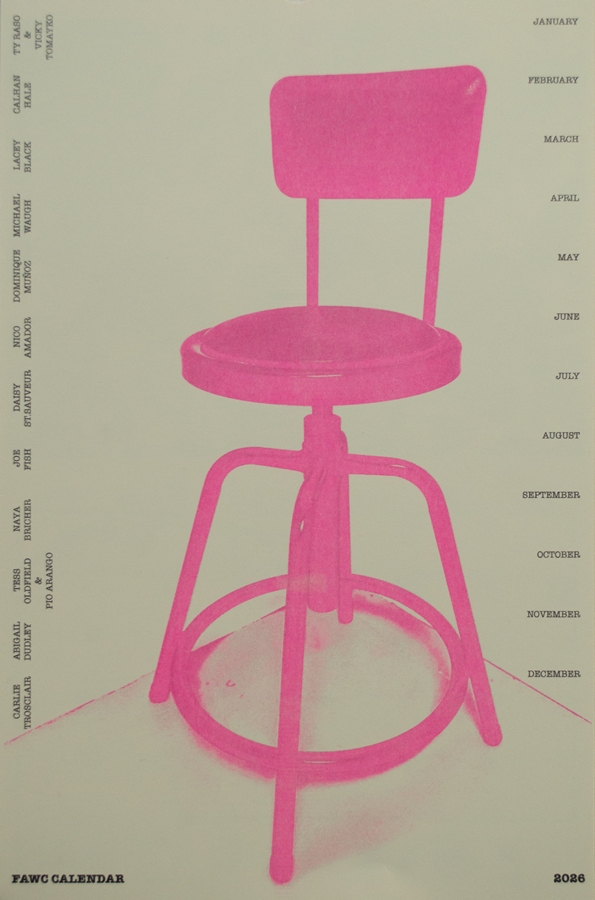

Dominique Muñoz, a visual arts fellow, assembles a calendar with wire binding in a common room at FAWC. The cover features an image of a tall metal chair printed in neon pink on a risograph. The pink vibrates against the cream-colored paper. Muñoz has been collaborating on this calendar with other fellows and with Vicky Tomayko, an artist and manager of the Work Center print shop. Each calendar page was designed by a different fellow.

Dominique Muñoz crimps together a stack of papers for a calendar.

Dominique Muñoz crimps together a stack of papers for a calendar.

This is the second year for the calendar project. It began in 2024 when the Work Center acquired a risograph through a federal grant for equipment to support community activities. Tomayko, who was a visual arts fellow at FAWC in 1985, had taken a one-day risograph workshop before the pandemic. It gave her a taste for the machine’s potential. S. Emsaki, the Work Center’s visual arts coordinator in 2024, knew about risographs as well and proposed the purchase. Together, the two did research to find the right one.

Last year’s fellows used the machine to make broadsides, posters, and postcards to publicize events. Last summer, two workshops were primarily focused on using the risograph. A few local people have used it to make zines, and Tomayko used it for a zine project with high school students from the Art Reach program at the Provincetown Art Association and Museum.

The risograph process can be described as a combination of photocopying and silkscreen printing. An image file is sent from a computer or placed directly on the scanning bed. The machine then uses the image to make a stencil by burning tiny holes into a tissue-like material. The stencil is wrapped around a large ink drum, and the drum pushes ink through the perforated stencil onto paper.

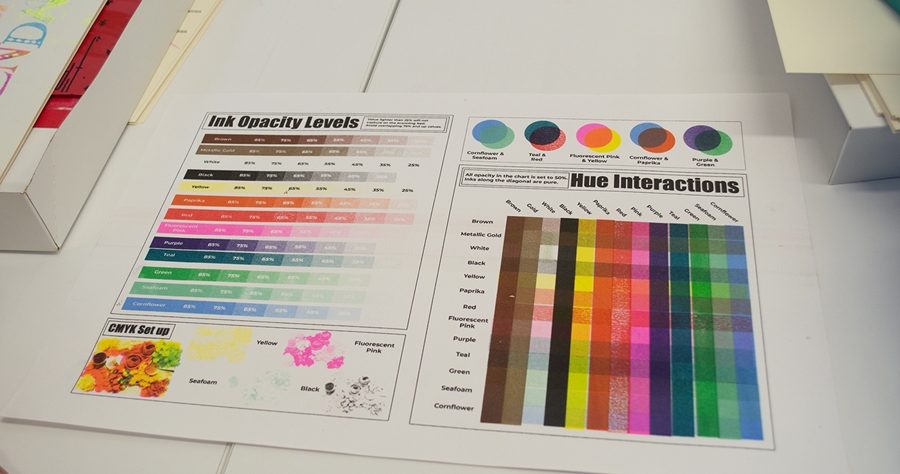

This chart details the ways that the risograph inks can be combined and layered to create more colors.

This chart details the ways that the risograph inks can be combined and layered to create more colors.

Tomayko says that one of the things that initially drew her to the machine was the retro look of the ink on the paper. Risograph colors are bright and transparent, making them ideal for layering. The Work Center has only five colors — red, yellow, blue, black, and fluorescent pink — but those five have endless mixing possibilities.

There are limitations to riso printing. Only one color can be printed at a time, so if you want to make a multi-color image, your paper needs to make repeated passes through the machine with the ink drum changed for the next color. “Big areas of solid color are not really possible, and the color registration and intensity vary from print to print,” Tomayko says.

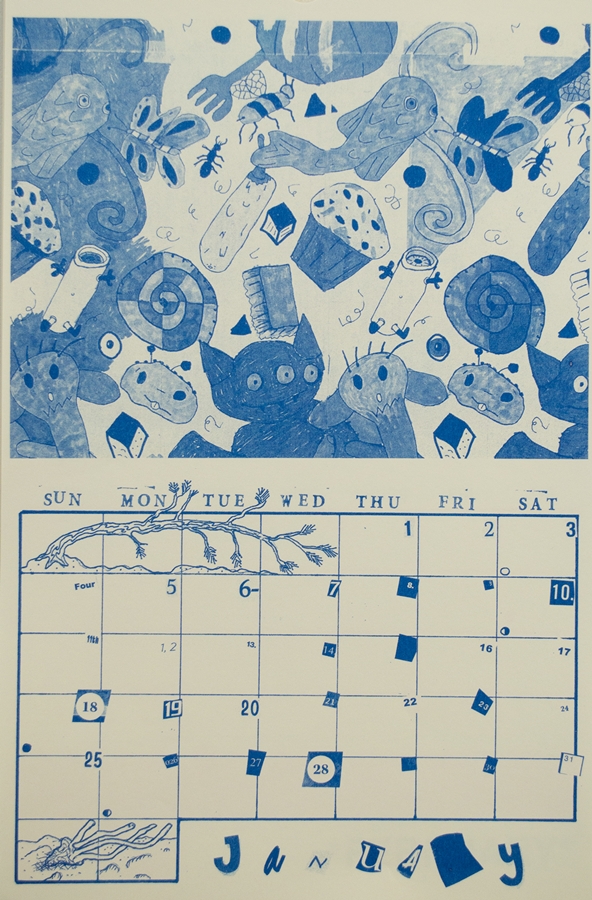

January calendar page by Vicky Tomayko.

January calendar page by Vicky Tomayko.

The printing can be finicky in other ways, too. You shouldn’t use thick paper because it jams the machine. It uses a specially formulated soy-based ink that never really dries. As a result, little bits of the previous color will be picked up and put back down in unwanted places on the paper. A newer stencil might make a cleaner print than an older one, but not always. There is a lot of hands-on problem-solving involved, and no two prints ever come out exactly the same.

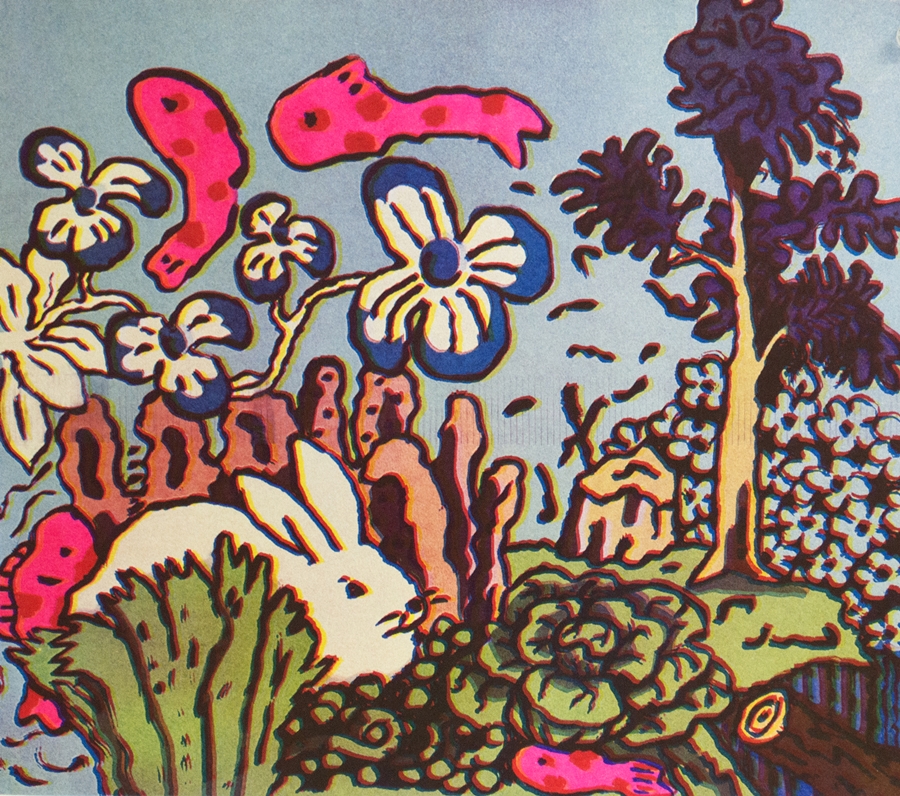

One of Tomayko’s prints is pinned to the wall above one of the computers. It’s a playful, colorful image where bright-pink fish swim above and through a landscape filled with whimsical plants, a white bunny, and a large head of lettuce. The image seems to vibrate, a result of the slight misregistration that leaves a small halo around each shape. Tomayko says she used red, yellow, blue, and fluorescent pink to print this image, but many more colors appear — golden yellow, green, a pale blue-gray, and black.

Calendar cover by Fine Arts Work Center fellow Michael Waugh.

Calendar cover by Fine Arts Work Center fellow Michael Waugh.

Tomayko uses Spectrolite, a free program for Apple computers and risographs, to figure out color separation, layering, and density. “It allows you to see how the image is going to look before you begin to print, and you can make adjustments,” she says. “You can see how your image would look with different color palettes or on different colors of paper. I like that if you have a vision, you can get it to happen without wasting any paper or ink.”

If you’re thinking all this sounds like way more fuss than it’s worth and why not use a nice, simple digital printer, then you aren’t thinking like a printmaker. Why an etching versus a lithograph? A screen print instead of a block print? A monotype instead of a collagraph? Each process has its own distinct advantages, disadvantages, and appearance. Likewise with riso. Many of these printmaking processes once had very practical applications — creating books, newspapers, posters — but today are kept alive by artists who use them for their distinct aesthetic properties.

Risograph print by Vicky Tomayko.

Risograph print by Vicky Tomayko.

Tomayko embraces the temperamental nature of the machine. “You have to work with the limitations,” she says. “Or maybe they are not limitations as much as they are a charming part of the appearance of a riso.”