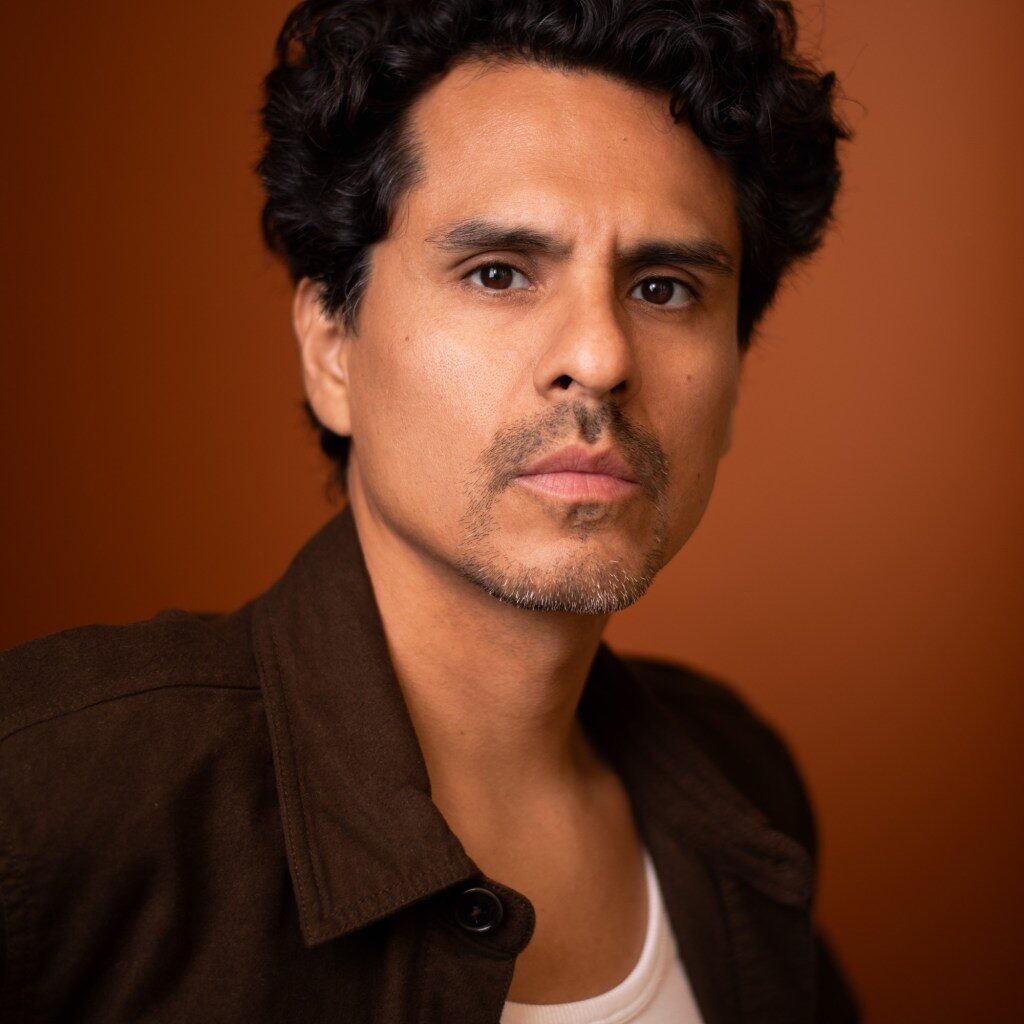

Reza Salazar has been a working performer for pretty much his entire life. After his parents divorced, his mother took 5-year-old Salazar with her, moving from place to place around South America, and performing as clowns to make money.

“I was ashamed of it for many years because it’s how we survived…I think, when I was little, I didn’t know any better and was just happy to be with my mother. When I started to get into the teenage years, I started to be a little bit more embarrassed about what we were doing. I didn’t want my friends to know that’s what I did on the weekend, that I dressed up as a clown,” he says.

He kept diaries that start in Spanish and transition to English when he and his mother arrive in the United States when he was in high school, documenting the moments of their lives together and the work they had spent so many years perfecting. He’s sharing his story in his play, “This Is Not an Immigrant Story,” part of The Old Globe’s Power New Voices Festival at 4 p.m. Sunday. The festival is a play reading event that features new plays by emerging and award-winning playwrights, including local artists, and continues through Sunday. Tickets to all readings are free and require reservations.

Salazar — who’s based in New York City and work includes Broadway, off-Broadway, film, television, and teaching—says the theater is his laboratory and sanctuary. That, in this upcoming performance, “I’ll offer a theatrical manifestation of my life story, the magical, realistic reconstruction of my memories. You can laugh, allow yourselves to be moved, be challenged, celebrate our shared humanity, and think about our mamas.”

Q: What was your familiarity with the Powers New Voices Festival and why did you want to participate in it?

A: To be honest with you, I wasn’t familiar with the festival, per se. I was familiar with the institution. In New York, you hear of theaters across the country, like The Old Globe and Berkley Rep and the Goodman in Chicago. Those are institutions that I always dreamed of working at, but I didn’t know how that was going to happen because they seemed so unreachable to me, but I dreamed of getting there somehow. The Old Globe was one of those theaters that I’ve seen in pictures that I would hear some people talk about, and I just didn’t know when and how I was going to be able to get there, but I dreamed. Imagine being in a place where you get to focus on your work. You get to get out of your house or your city and go somewhere else and just think about your work. What a luxury to be given that opportunity because even if I’m in New York, the grind never stops. So, the idea of leaving and being able to get a place to stay, and the resources and the support to be able to work on your projects, just sounded like a dream, so it’s a bit of a dream come true for me.

Writing is not a new thing for me because I’ve been a secretive writer for most of my life, but it is new in the sense that I’ve just really opened it up. My first residency was in 2021-2022 with a media production company in New York when I was still working on a TV project for the play that I’m writing right now. That was the first time I would say I officially put the writing forward. After that, little by little, little doors and windows are starting to open and I applied to other things and got another little residency with the New York Theater Workshop, and then with the Berkeley Rep last summer, and it was great. Even giving myself permission to write, how do people do it because I’m always grinding and surviving. With writing, you need to think; I’m busy surviving, so how do you do this? Who pays for that? Who supports that? I know what it is to work as an actor, and when I’m working as an actor, I feel like I’m working and I’m getting paid for my work. I’ve been doing it most of my life and that makes sense to me and I can do that. As a writer, I didn’t know who was going to support me sitting down at a desk. You know, sometimes there are days where I just write one page, so I was thinking, ‘Gosh, how do people do it?’ So, we hear about these residencies and things.

When I found out about Powers New Voices Festival, the idea is a festival more focused on the presentation, but this is not really a residency. It’s more like you get your team and you sort of work the piece. It’s very much focused on the work in progress. It is a reading and very minimal lighting and sound, which I like. I’m still there with this piece, I’m still moving things around and adding and editing, but the idea of the presentation focus is that it is meant to be presented to a group of people. Other ones I’ve had have really been up to the artists whether you want to open it up to an audience or not, so this is the first time I’m going to be doing it for the public. That scared me and excited me at the same time, especially because I’m out of my city. This is like, ‘Oh, my God, it’s a very South American-New York story, and I’m here in paradise. In San Diego. Are people going to care? Are they going to get it?’ I’m very curious. It’s the first time I’m taking it out of this habitat and putting it somewhere else with a community I don’t know as well, with a different rhythm, a different vibe. So yeah, I’m very excited.

Q: Your play is about your experience as a young child traveling through different countries with your mother, taking up street performing as clowns to make money. When did you decide that you wanted to share this part of your story in this way? Why was this something you wanted to write and perform in this format?

A: I never thought I will be sharing the story, but I’ve always written things down. For some reason, since I was very young, I still have my diaries since I was a kid. I kept moving to all these countries and brought them, even to the states. They start in Spanish and they transformed into English when I moved here. Even if I didn’t write them down, I have memories that I’ve kept, little details of life. I don’t know if that comes from always moving, so I had to retain certain things because I had the fear of things getting lost all the time. That could be one explanation I have. The other one is just that the type of nomadic, impulsive life my mother and I had, my mother was very young when she had me, so we grew up together, figuratively and literally. I guess my young brain was trying to make sense of what the hell was happening, so I had to write it down. Like, ‘Someday this will make sense.’ I was very aware that there were certain things that I couldn’t discuss with my mother, that she didn’t have the capacity to have that conversation, so I had to write it down, I had to remember it. I’m like, ‘Some day, I will go back to this. I will revisit this moment.’ So, I had this archive, I guess; mental archives and writing diaries.

I didn’t know what this was going to be, but for a few years now I did start to have the urge of wanting to do a one-person show. I’ve always been a fan of one-person shows — John Leguizamo, David Cale, Spalding Gray. I just love the simplicity of the storytelling that a one-person show could bring. There’s someone just sitting on stool with a microphone and telling you a whole story, or offering a play with nothing but a stool and microphone, and somehow you see everything. As an actor, I’ve been fascinated by the power of just one human being on stage making a play, so that’s something I held on to. In streets of Latin America, you see a one-person show, a stand-up comedian in the plaza, just someone surrounded by people telling jokes. That’s very common in Latin American and I grew up watching the power of that, of bringing people together with one person, no props, no lights, no sound, just charisma, magnetism, and a compelling story. I guess I’ve been fascinated with that very minimalistic, bare bones power of a story. That’s on the professional level. Then there’s the urge of telling the story recently on a more, maybe spiritual sense. At some point we start thinking about our parents as human beings, as men and women, and I’ve been going through that myself. That has been very inspiring, just to see my mother as a woman, as a human being. There’s something about going back to those stories and those thoughts and memories, and making sense of them.

Q: Why isn’t this an immigrant story? What comes to mind for you when you think about how stories about immigrants are typically told/portrayed, and how is your story different?

A: The mother-son relationship has always been the essence of it, the engine, but the rest of it, I didn’t know where the piece was going to take me. I didn’t want to write something chronologically, that was very clear to me, so I go between present and past. And, immigration is very much on my mind and in my heart right now, and it’s always been. I’m an immigrant, my mother’s an immigrant, the people around me, the people I love are immigrants. That narrative is very tangible to me, but I didn’t want my piece to be an “American Dream” story because I felt like that puts us in a box, in a way. It just distills it to a very one-dimensional place and I feel like immigration is a lot more complicated, messy, and more beautiful than that “American Dream” way. Without getting too political, immigration is more complicated than just wanting to come here to fulfill your American dreams. People are persecuted, people come here because of the stuff that America is doing to other countries. I think it’s human, as well, to want to move. It’s very human and normal. We’ve always done it, humans have always moved around, so we’ve done that. Young people want to go and explore the other side of the world, and that’s normal to me. The other side is you do it because you have to, not because you necessarily want to. So, to me, there are a lot more complexities to it. There’s also a sacrifice that is being made when you leave your hometown or your country. There’s a big sacrifice that you make. People come to create some sort of material stability, but there’s other factors to life—family and emotional stability, mental health, all of these other things that we sometimes sacrifice for this economic stability.

Even though I started writing this piece before all of this was happening, the way immigration is looked at right now is influencing my piece because I always felt that, as immigrants, we become this one-dimensional being when we come here. We just become immigrants. I remember when I was 13, I was so scared that all of that life that my mother and I had before we came here was just going to be lost and we were just going to be immigrants now. That this is our new title, “immigrants.” All of those adventures and all of the stories, we’re now just going to forget about them in this new place. I always call this “This Is Not an Immigrant Story” to be a little cheeky, in a way, I just wanted to shine light on immigration in a way that is a bit more complicated than just the category that it falls into. These are human beings like anyone else. They happen to immigrate here, but they have all of the complexities and difficulties and celebrations and beauty and colors of any other human being. I just had to word it like that, “This Is Not an Immigrant Story,” because this is a story of a human being who happens to move to this part of the continent, happens to think in two different languages. My piece is somewhat bilingual; not that I take pride in Spanish myself, I don’t. To me, Spanish is also not my language, it was another colonizer language.

Q: What do you want to say/communicate to audiences in “This Is Not an Immigrant Story”? Has the contention and hostility from government agencies and legislation toward immigrants here informed the things you want to say or the ways that you want to say them?

A: Part of me being an actor wants to allow the audience to feel whatever they want to feel because my job as an actor is to tell the story-to tell it well, to tell it truthfully, and then whatever the audience gets from it, hat’s not my concern, in a way. I don’t want to dictate what the audience feels. I want to leave room for discovery when I’m up there on stage. When people laugh, when people when people are moved, when people are quiet, when they laugh in unexpected places, when they’ll laugh in places that I thought were funny-all of those things are part of that journey.

The writer part of me wants to be able to, if I can, contribute something. I’ve got to be honest with you, something’s happening right now that really makes me freaking sad. It’s just heartbreaking. Not that it’s ever been good for us, it’s always been America, an experiment. It’s never been great, but I find myself counting how many people of color are in the room, looking at where the exits are and if I’ve got to run out? Walking out of spaces sometimes because I don’t feel comfortable there? It’s heartbreaking and I think it’s unjust for all of us, including White people because I think that I feel like most people are good, I really do. I think most people do have goodness in their hearts and we learn and we mimic all of this stuff, sometimes through ignorance, sometimes through isolation. There are so many devices that are doing a great job at keeping us isolated, divided. It takes more work now to be able to be more aware of those devices. So, part of me does not want to dictate and wants to discover because I am a storyteller, first and foremost, so my job is to tell you the story. The other part, and I don’t know if this sounds cheesy, but my contribution is ‘Can you see me? You’re going to see a brown man on that stage, telling a story; can you just see a human being? Can you see the commonality of our humanity? Is it possible?’ So, that journey of seeing just a human story, just being able to see the humanity of a brown man who’s an immigrant and who may or may not speak Spanish, he’s telling you this story. Can you still just be present and see the humanity? Enjoy the story like any other any other story, any other play by anyone you know, by any other human being, and still connect and still be moved and still go on a journey with me? And if it makes you think about your mama, that is a plus to me. If, on the way, this story can move you to think about your mother, I think I’d be happy with that.