Why did U.S. President Donald Trump order his lightning invasion of Venezuela and abduct its president on Jan. 3? Was it for oil, as Trump boldly insisted immediately after? To remove a corrupt dictator? To (somehow) curb narcotrafficking? To bolster his immigration crackdown? To posture in front of international rivals? To distract from economic woes, his exposure in the Jeffrey Epstein case, or his declining popularity at home?

It’s a trick question—it was for all those reasons and more. The incursion was what both theorists and screenwriters call “overdetermined,” a situation in which there were possibly dozens of probable causes, any of which could have sufficiently explained the motivations for it.

And while some Trumpian positions, such as his obsession with annexing Greenland, are products of his own unique pathologies, overdetermined interventions have been a feature of U.S. foreign interference for well over a century.

This has been especially true in Latin America—a region that American imperialists have long considered an extension of U.S. property, justified by ahistorical invocations of the so-called Monroe Doctrine and reflexively referred to as “our own backyard.”

Take Nicaragua, which Secretary of State Marco Rubio already has in his sights after Venezuela. The United States repeatedly intervened in the Central American republic from 1909 through the 1980s. There were many motivations from the start. President William Howard Taft had inherited from his predecessor, Teddy Roosevelt, a sprawling list of imperial commitments, from crushing a rebellion against U.S. colonial rule in the Philippines to continuing construction of a transoceanic canal in the new client state of Panama, which the Roosevelt administration had helped create for that purpose.

Roosevelt and his allies had considered digging the canal through Nicaragua; when it decided on Panama instead, Nicaraguan President José Santos Zelaya began making inroads to potential European partners, including the Germans and Japanese. He also rolled back concessions for U.S. investors, especially in the mining sector, and raised taxes on foreign investors.

In late 1909, a conservative Nicaraguan general launched a coup against Zelaya, cleverly enlisting a colonel who happened to be the accountant for a Pittsburgh-owned mining concern. Taft’s secretary of state, Philander Knox—himself a former corporate lawyer from Pittsburgh— officially denounced Zelaya as a “blot upon the history of Nicaragua” and painted the putschists in democratic language, claiming that their “revolution represents the ideals and the will of a majority of the Nicaraguan people more faithfully” than the president.

Four days later, Taft ordered a battalion of Marines into Nicaragua to support the coup. Zelaya resigned and fled to Mexico. With that completed, a State Department operative, Thomas Moffat, was dispatched to Nicaragua to impose a new debt to the Wall Street banks of Brown Brothers and J.W. Seligman and Co., which two years later would use their leverage to incorporate a U.S.-run central bank of Nicaragua, headquartered in Connecticut. When Nicaraguan rebels rose up in opposition to the overwhelming U.S. presence, more Marines were deployed, growing into a full-scale U.S. occupation that would last until 1933.

Any one of those motivations—protecting access to the Panama Canal, blocking out the Germans and Japanese, “democracy,” protecting and growing the investments of U.S.-owned mining companies and banks, protecting U.S. citizens’ lives—would have been sufficient to explain the intervention. But taken together, building on one another, they created a fallacious sense of near-inevitability. Taft—and then Presidents Woodrow Wilson, Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover—felt that he had to intervene militarily, lest the whole house of cards come tumbling down.

It was not until President Franklin Roosevelt decided to do things differently, embarking on his “Good Neighbor” policy to enlist the Latin American republics as allies rather than mere sources of extraction, that the U.S. occupation of Nicaragua ended, albeit with the country in the hands of a U.S.-backed dictator, Gen. Anastasio Somoza García.

Opposition to the abuses and corruption of the Somoza dynasty and memory of the past U.S. invasions and occupation would harden into the Sandinista movement of the 1970s—named for a rebel leader in the 1930s. Their rise to power spurred President Ronald Reagan’s CIA in the 1980s to arm and back Contra death squads, which were financed—among other things—with cocaine trafficked to the United States and funds illegally transferred from weapon sales to Iran.

Nonetheless, Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega remains president of Nicaragua to this day. Rubio, taking a page from Knox, has denounced Ortega’s government as an “enemy of humanity,” indicating that he may be on the list for a future round of regime change.

The commander of the first U.S. Marine battalion to land in Nicaragua in support of the 1909 coup was Maj. Smedley D. Butler. He identified the ulterior motives immediately. In a letter to his parents from the country, he wrote: “What makes me mad is that the whole revolution is inspired and financed by Americans who have wild cat investments down here and want to make them good by putting in a Government which will declare a monopoly in their favor.”

Butler swallowed those complaints and went on to a spectacular military career: twice awarded the Medal of Honor and a veteran of no fewer than 15 equally overdetermined U.S. interventions, including in Mexico (oil, fear of German or British intervention, requests for protection from U.S. business interests, and Wilson’s personal distaste for the Mexican dictator) and Haiti (debts to and investments by U.S. banks, primarily what is now Citigroup; regional instability; abject racism; fear of German intervention). He retired in 1931 as a major general.

In retirement, Butler would become an outspoken activist against both war and U.S. empire, denouncing war as a “racket”—“something that is not what it seems to the majority of people … conducted for the benefit of the very few, at the expense of the very many.” Soon after, he denounced himself as having been a “racketeer for capitalism.”

Butler’s analysis was simplistic: In reviewing his career, he would find one ulterior motive—generally the most venal one, purposefully hidden from the U.S. public (banking in Nicaragua and Haiti, oil in Mexico and China, fruit company profits in Honduras, etc.)—and seize on it as the sufficient explanation for the entire operation.

This was based on the supposition, long held or at least professed for most of American history, that the U.S. public is idealistically liberal, humanitarian, and instinctively democratic. It assumes that if Americans knew that we invaded Mexico in 1914 not just on a spree of Wilsonian idealism but for access to oil, or Iraq in 2003 for the same, that it would have sapped public support for those wars and prevented new ones.

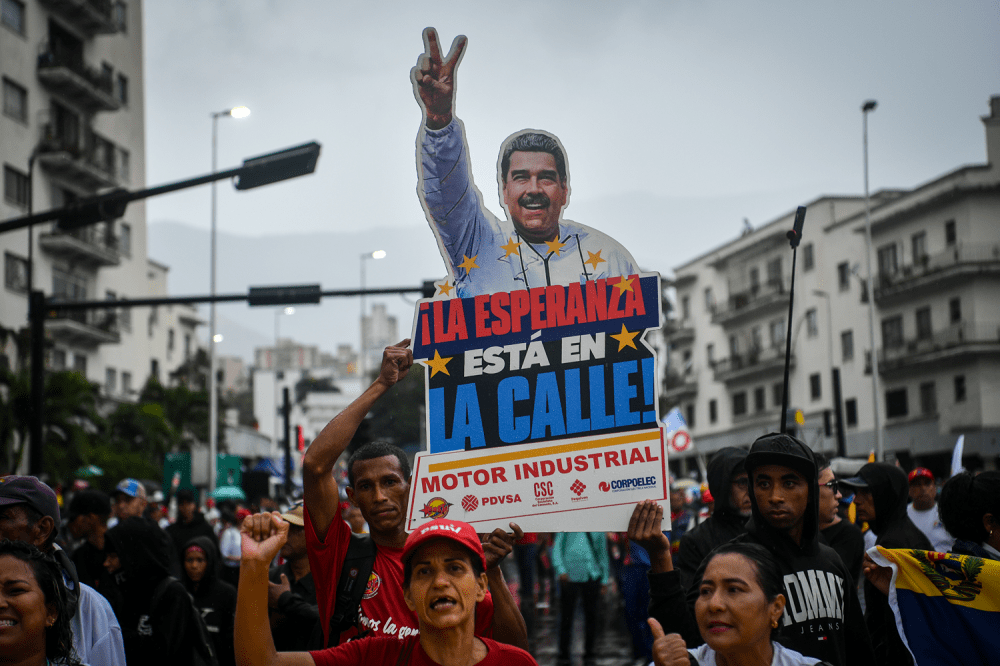

Trump is testing that thesis. In announcing the capture of Nicolás Maduro on Jan. 3, he gleefully made clear that seizing Venezuela’s prolific oil reserves was one of his primary motivations. (“We couldn’t let them get away with it,” he said. “You know, they stole our oil.”)

That major U.S. oil companies are not champing at the bit to return to Venezuela is, for him, beside the point; he will be a gangster for capitalism whether the capitalists want it or not. At his press conference, the word “democracy” did not come up even once. Nor did he seem eager to hold or even call for new Venezuelan elections. His base seems, for the most part, unperturbed by this total abandonment of even the pretenses of liberal internationalism. Americans are deeply split on the rights or wrongs of intervention in this case.

As in all the past interventions, there are numerous visions at play: Rubio’s anti-communist dreams of overthrowing leftist governments across the region, especially in his parents’ native Cuba; Stephen Miller’s unrepentant neocolonialism at home and abroad; or Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth’s fragile desire for an ultra-manly, “anti-woke” force that projects “maximum lethality, not tepid legality.”

All of these are combined and papered over by what the administration’s National Security Strategy calls the “Trump Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine”— the “Donroe Doctrine” as it has been nicknamed—whose stated goals are to “restore American preeminence in the Western Hemisphere,” “discourage mass migration,” and ensure “our access to key geographies throughout the region.”

All of those motivations can be successfully argued against on both practical and moral grounds. But overdetermination creates its own defense: Critics who focus on oil are told that it’s really about immigration; those who dispute the drug-trafficking narrative are asked why they’re defending a dictator; those who point to Trump’s hypocrisies or crimes—or the fact that Maduro’s regime is still very much in place—are reminded of the United States’ long history of backing authoritarians around the world.

Today’s Smedley Butlers—whether in the military, government, public, or press—will have to find a way to fight against all of them at once.