When President Trump declared that help was on the way and invited the Iranians to attack their institution, there was some support here. And fear, of course. The last war with Iran six months prior left many Israelis even more traumatized, with several casualties and an entire neighborhood razed in the country. Yet, when he backed up a few days later, the disappointment in Israel was palpable. And many felt some guilt as well: We are abandoning the Iranians!

Many Israelis have been expressing their solidarity with the Iranian people, who are risking their lives to challenge an authoritarian regime that has maintained control for decades through repression and fear. Social media is filled with messages of support, calls for freedom, and admiration for the bravery of the protesters in Iran.

Some Israelis have gone further, writing that if Iran retaliates against Israel after a possible American strike, they are ready to spend days or even weeks in bomb shelters, as they did during the war in June 2025. They frame this willingness as a form of moral contribution – a small personal sacrifice that might help free Iranians from a regime that fuels regional instability while brutally repressing its own people.

I understand this sentiment deeply. I share it and feel it, too.

I have worked with Iranians, many of whom no longer live in their country because dissent became unbearable, or their lives were at risk, for things as unbelievable as teaching yoga. I have listened to stories of prison cells, surveillance, forced exile, and families separated indefinitely.

Credit: Ronny Edry/Peace Factory

What we are learning today goes far beyond mere repression. We are witnessing reports of mass executions carried out in public spaces by the regime, the Revolutionary Guards, and affiliated militias, against their own population. With the internet repeatedly cut off, what reaches the outside world may be only a fraction of what is actually unfolding. The true scale of the violence is likely far worse.

And yet, Iranians continue to rise. After decades of fear, they are openly challenging a system built on terror, demanding its end, knowing full well the price they may pay. This is no longer only resistance; it is a revolution, carried by extraordinary courage and sustained by the support of an entire global diaspora that has refused to look away.

In this context, the desire to stand with the Iranian people is not naïve. It is profoundly human. Even the calls for U.S. intervention — controversial and fraught as they are — should be understood for what they often are: not warmongering, but desperation born from the belief that internal revolt alone may not be enough to dismantle a regime that has survived for decades by crushing its own society.

And yes, if supporting their struggle meant spending days in a shelter, I would do it too.

But there is something deeply disconnected about how this conversation is conducted in Israel, shaped by a distance from the actual cost. Because not everyone here has a shelter to go to. When Israelis speak of resilience and shared risk, they often assume protection: reinforced walls, a sealed room, a shelter nearby. For tens of thousands of Bedouin citizens in the Negev, this is not the case.

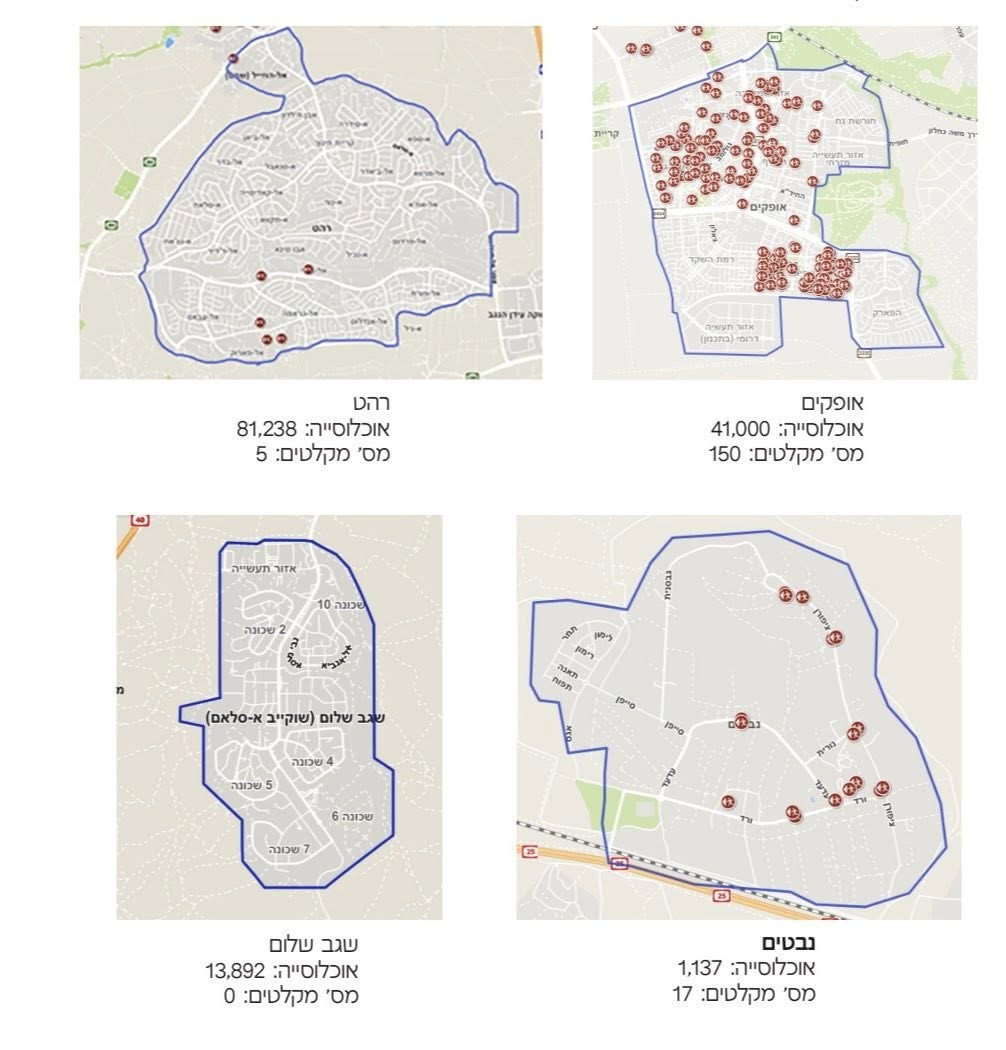

Just last week, during a discussion at the Knesset about civilian protection in southern Israel, the NGO I work for, the Negev Coexistence Forum for Civil Equality, presented figures that shocked everyone in the room. In Ofakim, a Jewish town with approximately 41,000 residents, there are around 150 public bomb shelters. In contrast, in Rahat, a Bedouin city with more than 80,000 residents, there are only five bomb shelters. Just five.

Negev Coexistence Forum for Civil Equality (NCF)/Nagabiya Research on protected spaces in the Negev.

These numbers result from decades of planning policies, budget allocations, land regulation, and political priorities. The committee chair was stunned and announced that an urgent letter would be sent to the Prime Minister, with another parliamentary discussion scheduled… in March.

As multiple media outlets once again report on the possibility of an imminent U.S. strike on Iran, and the likelihood of Iranian retaliation against Israel, even the familiar phrase “too little, too late” feels painfully inadequate.

On October 7, seven Bedouin citizens of Israel were killed by missile strikes. Five were children. Four were siblings from the same family, killed instantly in their home by a rocket fired by Palestinian Islamic Jihad – a small projectile compared to Iranian ballistic missiles.

During Iran’s first direct attack on Israel in April 2024, the only civilian seriously injured was a seven-year-old Bedouin girl. She was struck in the head by missile debris while sleeping. She is still undergoing treatment today.

Since October 7, the Negev Coexistence Forum for Civil Equality and its research center, Nagabiya, have been mapping shelter access across Bedouin communities – recognized and unrecognized alike – while conducting interviews with families, educators, and local leaders. We have documented gaps, shortages, unsafe structures, and bureaucratic barriers.

There have been improvements: temporary installations, mostly. But progress has been fragmented and painfully slow.

Temporary bomb shelters were installed after October 7 in Al-Goran, a Bedouin village where four children were killed in a direct missile strike. Credit: Chloé Portheault

After long and difficult advocacy efforts, the State installed temporary protective structures in some Bedouin areas, mostly near schools, consisting mostly of thin metal cylinders known as miguniyot, or ESKO, designed to protect against short-range rockets. During Knesset hearings, Home Front Command officials admitted what everyone already knew: these structures offer no protection against heavy ballistic missiles used by the Iranian Regime.

Temporary HESCO bomb shelters installed after October 7 in Al-Goran. Credit: NCF

During the recent confrontation with Iran, many Bedouin families lacked access to official shelters. As a result, they gathered under highway bridges, crowded into drainage tunnels, or sought refuge in sewage systems. In several villages, families dug makeshift holes in the ground, excavated sand and earth, and reinforced their shelters with metal sheets and wood. While this improvisation offered some protection in June, it became dangerous in January, when heavy rains flooded the Negev. Underground cavities filled with water, and the soil could collapse, putting entire families at risk of drowning.

Even many shelters across Israel no longer meet safety standards. And yet, public discourse continues as if access to shelter were a given.

An improvised shelter in a stormwater drainage tunnel, where a family took refuge during the June escalation. Credit: RCUV

Building proper shelters is rarely an option. Obtaining construction permits is nearly impossible in many Bedouin localities. Structures built without authorization, even when explicitly designed for protection, will be demolished by the authorities. But even if approved, such a plan would take years to implement. Years that geopolitical escalation may not grant.

It is not easy to speak of sacrifice when your children sleep behind reinforced concrete, but it is easier than when they are not.

And of course, even with shelters, the cost is high: economically, psychologically, and physically. Some twenty-five persons were killed during our last war with Iran. Many people lose their homes, their buildings, sometimes entire neighborhoods. Protection does not mean immunity from trauma.

Most Israelis sincerely hope for a free Iran, and their claim to be ready to endure hardship for that vision may be genuine. I count myself among them. But solidarity that ignores internal inequality is fragile at best — cynical at worst.

The right to survive missile fire should not depend on planning classifications or land-registration status.

We can and should care about the Iranian people, and recognize that our futures are deeply intertwined. Still, our solidarity with our Iranian brothers and sisters cannot come at the cost of ignoring inequality at home, and that some citizens are asked to face war without the most basic protection.