Join our zero2eight Substack community for more discussion about the latest news in early care and education. Sign up now.

As the pace of product development for AI-powered toys accelerates, controversy — and warnings — about the appropriateness of these products for young children have left many parents and educators tempted to tune out or opt out. But as kids interact with AI more regularly, some experts say it’s important to teach kids what’s actually behind AI and how to use it responsibly.

A new curriculum focused on computer science and artificial intelligence aims to teach young kids to build, program and prototype together. In essence, students build their own machine learning models, solving problems, inventing characters and telling stories connected to their interests. The program, designed by Lego Education to be used in K-8 classrooms, offers project-based experiences for kids to work on in small groups. The lessons use Lego bricks, and some are screen free, while others require access to a device, such as a laptop or tablet, so kids can access an app which has a “coding canvas,” with icon-based coding.

Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, professor of psychology at Temple University and a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, commends Lego for using the science of playful learning to teach computer science. “When children learn to solve problems with hands-on materials,” she states, “they are more likely to not only learn material but to be able to transfer what they have learned. In my experience, the Lego team has always worked with scientists to develop teaching tools that are aligned with the very best science on how children learn. It is one of the few companies committed to this way of doing business.” (Hirsh-Pasek has collaborated with the Lego Foundation on other projects but did not take part in this initiative.)

In a significant departure from many other AI products, data from the children never leaves the computer. “A really strong perspective that we had was that we don’t want anybody else to have the data — we don’t even want the data. We want that to stay in the classroom and on the computer, said Andrew Sliwinski, head of product experience for Lego Education. From a technical and design perspective, Sliwinski said, “It’s much easier to just send data to the cloud or use one of the big APIs [Application Program Interfaces], or one of the big companies that are out there. But when you do that, you sort of betray that principle of being able to guarantee privacy and safety to the child, and to the parent and to the teacher.”

Maybe Big Tech could learn a thing or two from Big Toy.

In an interview with Mark Swartz, Sliwinski explains his role, the evolution of the curriculum and his hopes for AI more broadly.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What do you do at Lego Education?

My team is responsible for product strategy, design, engineering and, most importantly, the educational impact of our product. So really the development of our learning experiences from end to end. Lego stole me from the MIT Media Lab, where I worked on creative tools for children for many years, including, most notably, Scratch, which is a programming language for kids.

Were you in the classroom before that?

I started working in education in 2002. I was living in Detroit, working as a tutor, and I was invited to support students in Detroit public schools with the Michigan Educational Assessment Program, the state’s big standardized test [at the time]. I’ve basically been working in some way, shape or form in education ever since.

What do you see as the through line between that work, and what you’re doing now?

When I showed up in Detroit all those years ago, my biggest reflection was: These are kids that don’t see the purpose in mathematics. They don’t feel connected to it. They don’t understand how it connects to their lives. And so for me, it was like, “Well, let’s solve that problem.” And yeah, the rest is history.

Were you a Lego kid yourself?

We didn’t have Legos, but we had all manner of other building materials at our disposal, like cardboard boxes and wooden blocks and access to hammers and screwdrivers and all of that fun stuff. So I grew up building things and learning through making.

Why is it important for children to understand what’s behind AI?

The phrase AI literacy is being used a lot, and I think it’s being used in a very general way that is sometimes unhelpful. AI literacy is about more than how children use AI. It’s about those foundational literacies that help children understand what AI is, because I’m not just interested in children developing an understanding of how to use ChatGPT to do a specific project or a specific location. I want children to understand what probability is. I want children to understand that machines reason differently than humans do — and why that is. I want children to understand that AI learns from data, and that data can have biases, and that data can have ethical considerations, and that data output is only as good as the input, right? Garbage in, garbage out.

What does responsible AI education look like for young kids?

What we’re moving forward with with Lego education is really focused on … those foundations. The way that I sometimes like to talk about it with the team is: So much of what is being put in front of kids today is like learning how to use the black box of an AI model or an AI tool — I’m much more interested in giving the kids a screwdriver and letting them take the box apart.

But that last analogy is figurative.

Yes. There are no screwdrivers that come in the box, but not as figurative as you might think. In the tool, the kids actually get to train their own machine learning models … So a bunch of kids will work together in a group of four. That’s something that’s different. It is collaborative.

RelatedWhy AI Literacy Instruction Needs to Start Before Kindergarten

What lessons can we draw from the use of earlier technological developments, such as TV and the internet, in building products for young kids?

These technologies are most effective when they serve as a catalyst for joint engagement between children and adults together, rather than sort of acting as a digital babysitter, whether that’s cartoons or whether that’s Club Penguin [a Disney game that ran from 2005 to 2017]. …

One of the most powerful things that you can say to a child is, “I don’t know. Let’s go figure it out together.” And I think that there’s so much that parents and teachers and kids don’t know about AI, but that kids are curious about. And us expressing our own curiosity, and supporting that curiosity and engaging together is a really powerful thing.

What guardrails has your team put in place for young children?

When we started working on this, one of the things that was really important was to have a set of principles and a set of lines — we call them red lines, lines that we will not cross — because I think it’s so easy when you’re working in technology development to sort of lose track of some of those principles. We established that way, way early in the project.

Some of the ones that are maybe less apparent are things like [how] no data from the children will ever leave the computer. It is never transmitted over the internet. It is never saved to disk. It is never sent to Lego. It is never sent to any third party. And if you look at the predominant paradigm and a lot of the tools that are out there, that is not the case. …

…We’re the Lego Group. If we don’t care about child safety and well-being, who does? And so I think it’s been this huge responsibility, but also like this really great opportunity for us to put forward something that we feel lives up to our values. … People are always surprised by how much my team goes around the world testing in classrooms, testing with children and talking with educators and experts. We even have child developmental psychologists that are on staff. And so much of what we do is about developing the right things in collaboration with young people and educators.

How did you test the experience with young children?

One of the most recent tests that I [did] was testing some of the AI features for the very young kids — the kindergarten to second grade group [in Chicago public schools.] One of the things that we do as the product matures is we stop being the teachers in the classroom and we actually just give the box to a … teacher in their normal day-to-day classroom and we say, “Good luck.” And then we watch, because it’s not enough for the kids to have a great experience when we show up knowing the product and we teach it. … It has to work for the teachers, otherwise it doesn’t matter.

One of the most interesting, but also humbling things that you do as a designer for children and teachers is taking it into the field, right? Because all of the assumptions and ideas and intentions that you have, they go out the window when you put it in front of a 5-year-old. That process is just so rewarding.

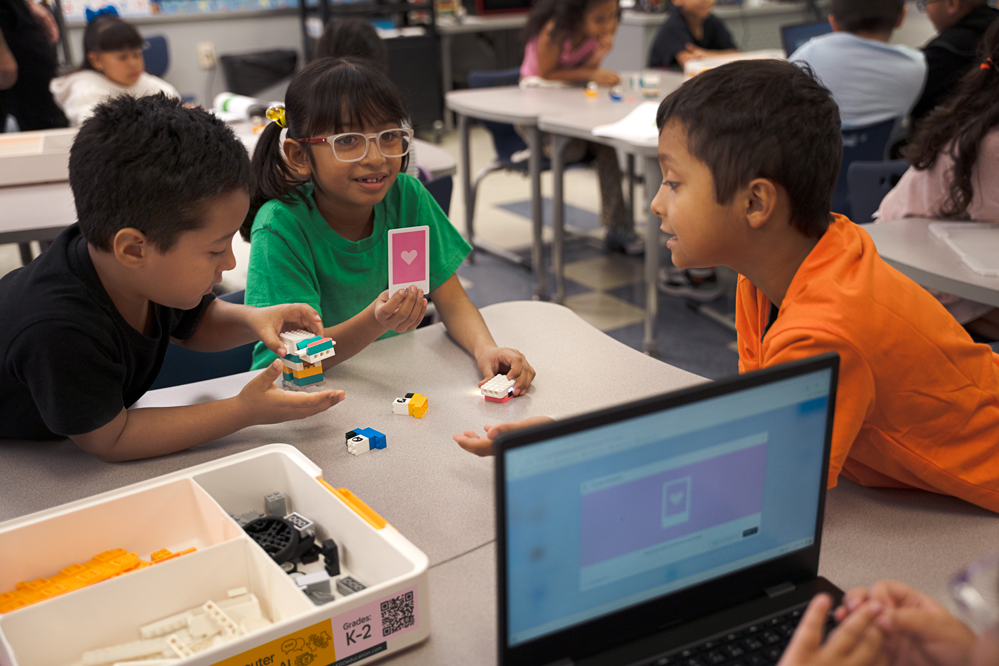

Second graders try out the new Lego Computer Science and AI kits. (Image Courtesy of Lego Education)

Second graders try out the new Lego Computer Science and AI kits. (Image Courtesy of Lego Education)

Did anything surprise you about how they put it to use?

I was observing a group of 4- or 5-year-olds, and they were working on this lesson where they had to build a toothbrush for a dinosaur. Part of that was figuring out how motors work and how sensors interact, but it was kind of a funny setup — the dinosaur mouth that we had built had these big teeth in it.

The 5-year-olds didn’t see a dinosaur. They saw a swimming pool, because the bottom of the dinosaur’s jaw had these big teeth around it, and they were like, “Oh, it’s a swimming pool.” So then they designed dinosaurs that went into the swimming pool.

You kind of come in with these stories and intentions of what you think kids are going to connect to. … And then you get there and it’s just one little detail of how the model was designed just throws the whole lesson out the window.

How are educators responding?

We’re doing this in a way where the teacher is able to come along for the journey, where we’ve prepared all of the materials that are necessary for a teacher, who often feels less confident about computer science and AI than their students do, giving them everything that they need to feel not just prepared, but to feel confident.

There’s this kind of power dynamic that’s happening with AI today, where we’re more focused on what computers can do than we are on what children can do right now. And I think that’s really fundamental to our approach … When you get a bunch of kids together to train a Lego robot how to dance, this kind of fear dissipates. They see the cause and effect between the model that they trained and what’s happening in the world, and they realize that the machine only knows what they taught it.

The AI is no longer the smartest thing in the room. They’re the smartest thing in the room, and the AI is a tool.

Did you use this article in your work?

We’d love to hear how The 74’s reporting is helping educators, researchers, and policymakers. Tell us how