Thinking of political violence solely as a safety issue is not enough to address the harm that follows. “The patient is the community.”

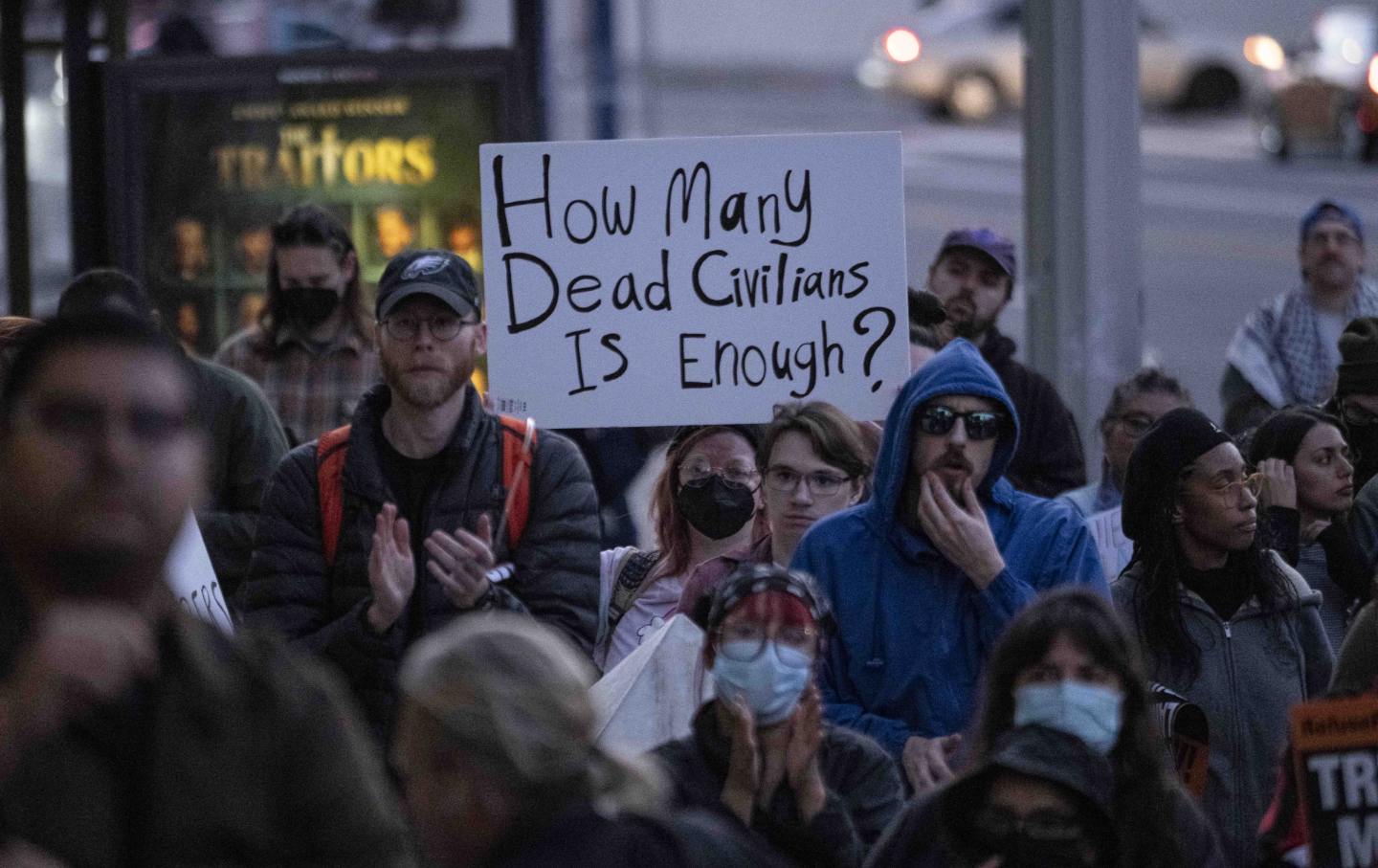

Protesters gather in front of the Federal Building at the protests for Renee Good and Alex Pretti.

(Jon Putman / Getty)

This story was produced for StudentNation, a program of the Nation Fund for Independent Journalism, which is dedicated to highlighting the best of student journalism. For more StudentNation, check out our archive or learn more about the program here. StudentNation is made possible through generous funding from The Puffin Foundation. If you’re a student and you have an article idea, please send pitches and questions to [email protected].

Mark Thompson, a young plumber from Orem, Utah, never imagined he would be affected by political violence. He was just another attendee in the crowd on a September afternoon, listening to a speech from a man he both agreed with and disagreed with. He was standing in line, waiting to ask his question, when the shots started. “Everyone just started running as we ducked and scrambled,” he said. “I felt a wave of fear I can’t even describe.”

Months later, that moment still follows him. A slammed door, a car backfiring, a phone dropping—any sudden noise can send his heart racing. “I walked out of the event alive,” he said quietly, “but part of me is still there, running away from a murder.”

The fatal shooting of Charlie Kirk in September 2025 revealed how routine political violence has become in America, and how easily a rally, a campus event, or a public forum can turn into a scene of chaos and fear. But it also revealed the limits of treating political violence solely as a safety and security problem.

Addressing the immediate threat, experts argue, is not enough to address the harm that follows. And today, the level of harm from political violence increasingly looks like a public health crisis.

Political violence refers to the deliberate use of force, which can include bombings, armed rebellions, or assassinations, by state or non-state actors to achieve political or ideological objectives. Between 2014 and 2020, the United States experienced a sharp rise in politically motivated violence, much of it driven by right-wing extremism. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies, there were 44 right-wing extremist incidents in 2019 alone, surpassing levels seen in the mid-2000s.

While those numbers dipped during the early months of the pandemic, political violence has resurfaced in recent years, fueled by renewed polarization, misinformation, and election-related tensions. Political assassinations have become increasingly high-profile, ranging from Charlie Kirk in Utah to Minnesota state lawmaker Melissa Hortman and her husband outside her home.

But the recent killings of Renée Good and Alex Pretti by federal immigration agents can be understood as forms of state violence tied to political agendas around immigration enforcement. State violence is not just the act of lethal force itself, but the legal and institutional systems that also authorize, normalize, and shield such actions from accountability.

Focusing only on body counts misses how political violence actually works, and its most immediate damage is often invisible. “People think political violence is just the moment someone pulls a trigger,” said Hassan Naveed, a longtime civil rights advocate and former architect of New York City’s Office for the Prevention of Hate Crimes. “But the real harm is what happens after: the fear, the vigilance, the way entire communities change how they move through the world.”

People withdraw from civic life, disengage from community resources, and avoid essential services like health care and education. Naveed emphasizes that this withdrawal is itself a measurable harm. “When people stop going to libraries, schools, or public meetings because they’re afraid,” he said, “that’s a breakdown in community health. At that point, the patient isn’t the individual. The patient is the community.”

For more than a decade, responses to gun violence have used a public health framework, offering additional tools to understand and prevent it, from epidemiology to risk-factor analysis. Political violence, however, has often not received the same treatment.

According to Linda Degutis, a public health physician and former director of the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, political violence has historically been handled as a national security issue, addressed largely through the criminal legal system.

But viewing political violence through a public health lens, she said, could help address both the root causes and its consequences. “I’m not saying we should stop viewing political violence as a crime,” said Garen Wintemute, an emergency medicine physician and firearm violence researcher at UC Davis. “I’m saying that a purely criminological approach doesn’t intervene far enough upstream. And in public health, we’re saying: let’s go farther upstream.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

According to Wintermute, many individuals who engage in political violence believe that nonviolent ways of resolving political disputes are no longer tenable. Often marginalized and isolated, they come to see violence as the only remaining form of participation available to them. Importantly, this pattern is not tied to any single leader or administration; similar dynamics have emerged under Presidents Trump, Biden, and Obama alike.

Wintemute once believed that a change in presidential leadership would shift the direction of political violence, resulting in more violence from the left under Republican administrations and less from the right. That expectation has not held. “For the first time in living memory,” Wintemute said, “we have an administration that encourages the use of violence. And we’ve now seen a domination of political violence from the right, and their violence is actually more deadly than violence from the left.”

Degutis argues that political leaders play a central role in either escalating or reducing this violence. Acknowledging disagreement, she said, does not require turning opponents into enemies. Divisive rhetoric, she warned, only fuels the fire.

Public concern over political language is widespread. A Reuters/Ipsos poll found that 63 percent of Americans believe the way political actors talk about politics encourages violence. Leaders on both sides increasingly describe opponents as existential threats. They call each other “enemies,” “vermin,” or “poison,” or warning of a coming “bloodbath.” Degutis argues that this framing can heighten fear and normalize violence as part of politics.

Wintemute likens this rhetoric to an environmental exposure. “When political leaders describe opponents as existential threats,” he said, “they’re not just venting. They’re conditioning people to see violence as a rational response. That fear doesn’t stay with one person; it spreads.”

Political violence kills and injures people, Wintermute said, but it also reshapes the social climate, making communities more fearful and more brittle. “After Charlie Kirk’s murder,” he noted, “the term ‘civil war’ spiked in searches. If that were to occur, the public health consequences wouldn’t just be the body count; it would be the social instability that follows.”

The long-term effects are especially pronounced for mental health. Even those who merely witness political violence can experience anxiety, stress, and lasting trauma. Over time, fear drives people away from public gatherings and civic participation altogether, weakening the foundations of democratic life.

“Incidents like Goode’s shooting deepen fear and distrust of government among immigrant communities and communities of color, even for those who were not directly involved”, Naveed said. “This reinforces the sense that interaction with public institutions is risky. Over time, this erosion of trust corrodes the relationship between government and entire communities, with lasting consequences for public safety, health, and democratic participation.”

Statistically, politically motivated violence remains rare. A Cato Institute analysis found that since 2020, such attacks accounted for roughly 0.07 percent of all U.S. murders. But public health experts see that as precisely why prevention matters: when a problem is relatively contained, intervention can change its trajectory.

This intervention, Naveed argues, starts with a basic public health principle: clearly defining and monitoring the problem. Political violence, he says, cannot be treated as a series of isolated incidents. It must be understood as a pattern of harm, one that can be tracked, studied, and prevented. That requires attention not only to acts of violence themselves, but to the conditions that make violence more likely: rising fear, misinformation, unequal enforcement, and the normalization of dehumanizing rhetoric.

In New York City, those conditions are addressed through the Office for the Prevention of Hate Crimes, which Naveed helped build as a coordinating hub rather than an enforcement body. The office’s role was to bring together agencies that touched people’s daily lives and ensure responses to hate and political violence were consistent, non-punitive, and grounded in civil rights.

One of the office’s first priorities was building situational awareness without turning to surveillance. Instead of relying on mass data scraping or predictive tools, the city partnered with trusted community organizations to establish multilingual reporting channels where residents could flag threats, harassment, or intimidation. That information shaped event-level awareness around rallies, campuses, libraries, and houses of worship, for example. “Once prevention becomes about profiles,” Naveed said, “you lose trust, and trust is the intervention.”

Clear, credible messaging is another factor. Wintemute has found that while roughly 80 percent of Americans say they would not want to participate in a civil war, among those who say they might, the likelihood of participation is cut nearly in half if a trusted family member, friend, mentor, or community leader intervenes. The finding underscores how prevention often works through relationships rather than force. As a result, public health responses focus on mobilizing political leaders and everyday citizens as credible messengers who can reinforce nonviolence as a social norm.

In New York, public health leadership came from the Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, which treated political violence as a population-level harm. Health officials coordinate trauma response and mental health care when fear spreads beyond direct victims. “We were very intentional about taking a harm-reduction approach,” Naveed said. “That meant understanding how fear was affecting communities and coordinating across health, education, and community agencies instead of defaulting to enforcement.”

Those principles translated into concrete interventions. For example, when drag story hours faced threats, community organizations—supported through city funding—deployed trained volunteers to form protective buffers and provide safe accompaniment for families. Schools and youth programs became frontlines as well. The Department of Education coordinated counseling and outreach when incidents affected students, while the Department of Youth and Community Development funded programs aimed at reducing isolation and building cohesion before tensions escalated.

Immigrant- and faith-facing agencies ensured that reporting systems and services were accessible to communities unlikely to call 911. Law enforcement remained involved, but intentionally not in the lead. “If everything defaults to arrest,” Naveed warned, “you lose communities before you prevent violence.”

Naveed also argued that responding to state violence, like federal agents’ killing of Alex Pretti, demands a public-health approach rooted in community safety and true accountability. This means organizing not just within communities but around the government itself, insisting on transparency, independent oversight, and mechanisms that confront and transform the systems that produce harm.

Degutis emphasizes that no single agency can do this work alone. “Coordination through a multi-agency group, with input from people affected by and exposed to political violence, is what allows strategies to work,” she said. Criminal justice systems can still hold perpetrators accountable, while public health and mental health providers ensure access to counseling, therapy, and preventive support for victims and witnesses.

The hope, advocates say, is that these efforts meet people long before violence does—rebuilding trust, lowering the temperature, and preventing crises instead of simply responding to them. When asked whether that kind of approach could help, Mark didn’t hesitate. “If it keeps someone else from going through what I did,” he said, “then it’s worth trying. No one should have to carry this.”

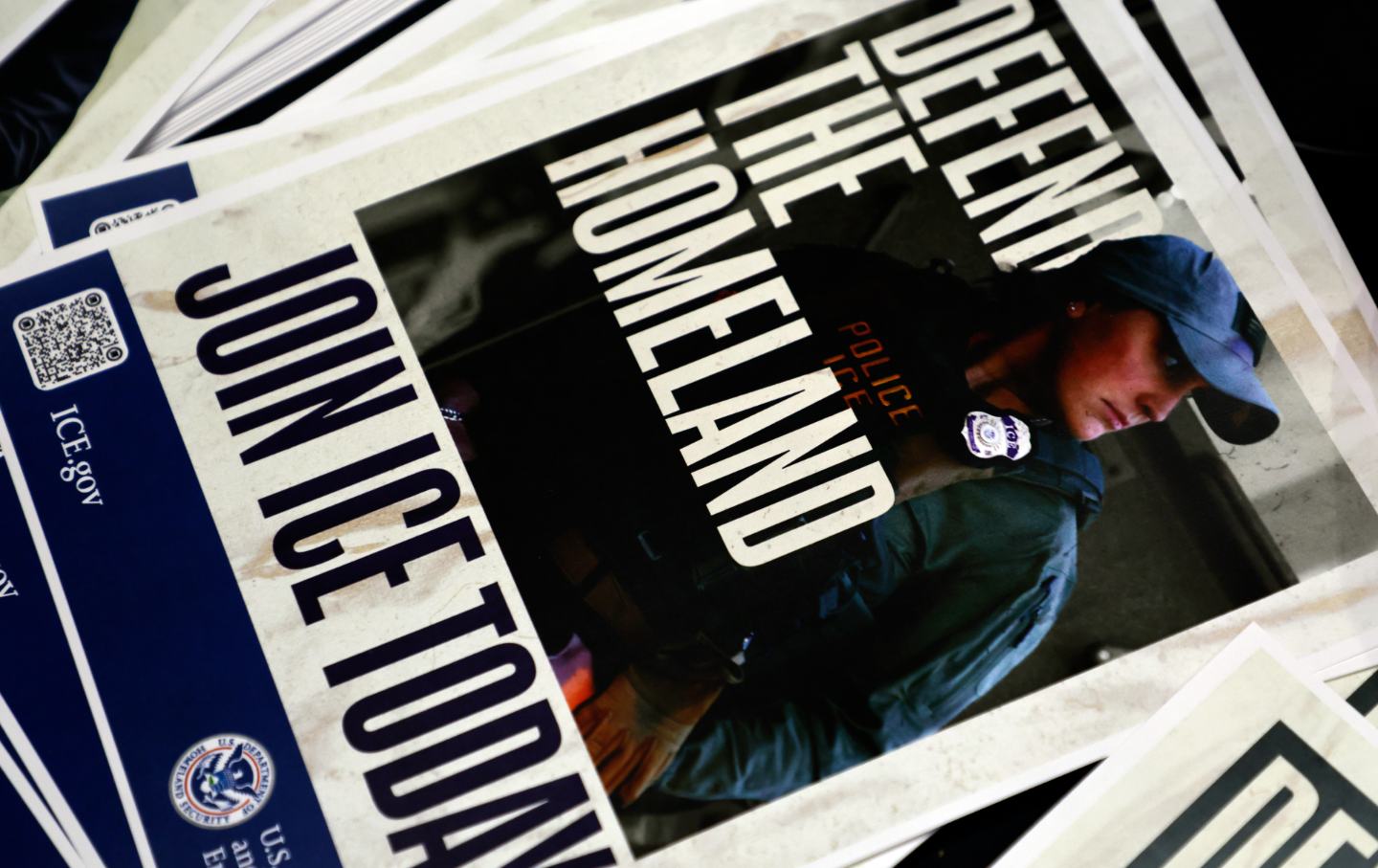

As a Black man, I know firsthand how often state violence is used to perpetuate white supremacy in this country.

ICE has lowered standards to facilitate a massive hiring spree. Many of the new recruits are plainly unqualified. Are some also white supremacists or domestic terrorists?