Image Source: Getty Images

As dusk descended over Belém on 21 November 2025, climate negotiations unfolded in an atmosphere dense with anticipation and strategic calculation. Delegates worked extensively to finalise emission-reduction timelines, establish measurable sustainability targets, and define the financial architecture required to underpin global climate commitments. At its core, the negotiation process reflected not a moral deliberation but a contest of influence—a dynamic shaped by the capacity of parties to marshal political and economic power and to mobilise public support for their respective positions.

This behind-the-scenes manoeuvring adds an element of intrigue and complexity to the overall climate negotiation process, leaving many questions unanswered about the true dynamics at play. In recent years, climate change negotiations have evolved into one of the most intricate channels of international diplomacy, marked by notable milestones and ongoing challenges. Since the historic adoption of the Paris Climate Agreement on 12 December 2015, opened for signature on 22 April 2016, and entering into force on 4 November 2016, which committed nearly 200 countries to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels, the global response to climate change has taken a variety of complex and non-linear paths.

Climate Finance: Ambition Built on a Fragile Foundation

Although the Paris Agreement was celebrated for setting a framework that encourages accountability and transparency, it has also exposed divergent perspectives on how to effectively tackle this existential crisis and delineate responsibilities between developed and developing nations. In reviewing the outcome of COP30, the Belém Package—often referred to as the “Mutirão” Declaration—was endorsed by approximately 194 Parties. The package addressed a wide spectrum of issues, including just transition, finance, adaptation, mitigation, gender, and deforestation.

The passage of the Belém Gender Action Plan represents a potentially significant step, placing stronger emphasis on women’s leadership, political participation, and addressing structural barriers that restrict women’s influence in climate decision-making at national and international levels.

On the question of who should pay for climate action, in a significant decision, parties agreed to build on a triple climate finance flow by 2035, including an aspirational mobilisation of about US$1.3 trillion per year by 2035. A list of 59 indicators was adopted, albeit with compromises that may make them more difficult to operationalise. Furthermore, of the 194 entities and countries that sent representatives to COP30, a significant number of Parties had yet to submit their updated 2035 Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The postponement of submissions poses a significant challenge to effective planning of climate finance under the framework of the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG). This delay complicates the accurate assessment of financial needs and hinders the strategic allocation of resources necessary to address climate-related initiatives. As a result, it becomes increasingly difficult to identify which areas require urgent financial support, potentially slowing progress in combating climate change and undermining the overall effectiveness of climate finance efforts.

Just Transition Matters

In another significant development on the mitigation front and for climate justice, the Just Transition Mechanism was considered. It is one of the key pathways to support developing and least developed countries in enhancing technical assistance, capacity-building, and knowledge sharing. This is being implemented via a new mechanism: the Belém Action Mechanism (BAM) for a Global Just Transition. One of the important aspects of the Belém Action Mechanism is its emphasis on labour, environmental, and human rights issues. Building on the Katowice Just Transition Silesia Declaration (2018) at COP 24 in Poland, the mechanism represents a partial shift in global climate governance, moving beyond broad principles toward more actionable frameworks. Although it is not a mandatory reporting requirement and carries no penalties for non-compliance, it still constitutes an important step, fostering dialogue among governments, workers, employers, and unions.

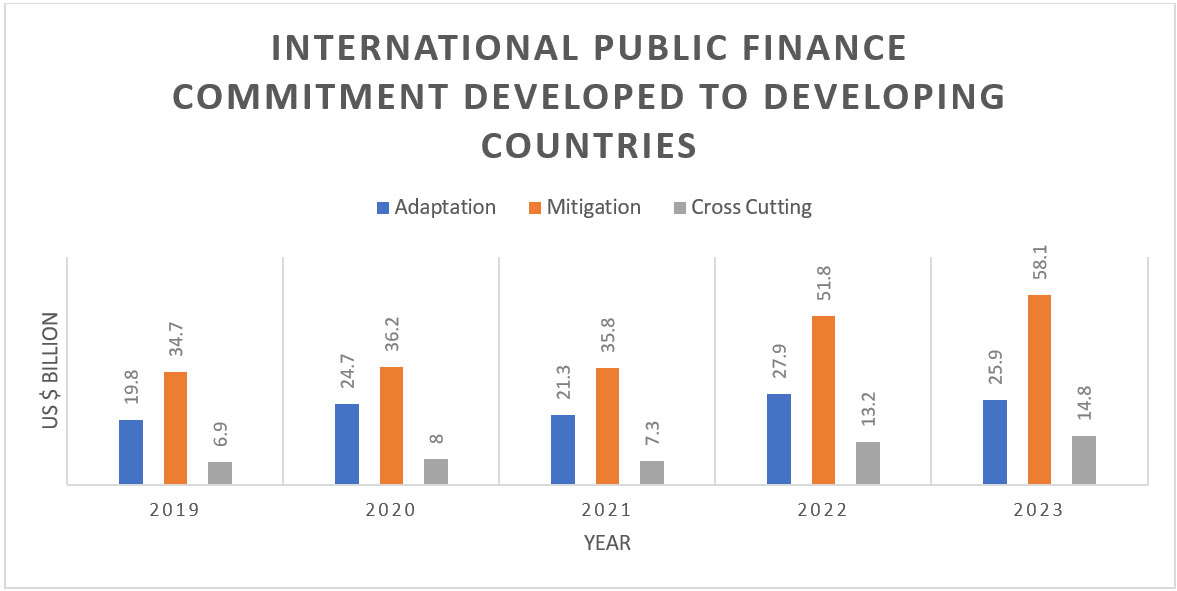

Developed nations have fallen behind their goal of mobilising US$100 billion annually by 2020 to support climate actions in developing countries, which undermines trust and collaboration.

Another notable commitment that has emerged is the pledge from more than 100 countries to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050, potentially encompassing around 85 percent of the global economy. This ambitious global climate commitment underscores the need for inclusive frameworks that not only reduce emissions but also ensure equitable participation. The Lima Work Programme on Gender (2014) laid the foundation by calling for women’s participation, capacity strengthening, and gender-responsive climate policies. The passage of the Belém Gender Action Plan represents a potentially significant step, placing stronger emphasis on women’s leadership, political participation, and addressing structural barriers that restrict women’s influence in climate decision-making at national and international levels.

In this context, it will be vital to reflect on remaining critical issues, such as the adequacy and fairness of climate financing. Developed nations have fallen behind their goal of mobilising US$100 billion annually by 2020 to support climate actions in developing countries, which undermines trust and collaboration. Additionally, conversations surrounding adaptation strategies for climate-vulnerable populations, as well as the urgent need for innovative technologies and practices, remain more pressing than ever. Addressing these unresolved topics will be essential for negotiating a more effective and equitable global response to climate change, thereby illuminating the path toward a more sustainable future for all.

Source: UNEP Adaptation Gap Report 2025

Another notable announcement was the launch of the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF) at the Leaders’ Summit to protect tropical forests. The TFFF Launch Declaration was endorsed by 53 countries, including 34 tropical forest countries, and has already mobilised more than US$5.5 billion in initial commitments, with major pledges from Brazil, Indonesia and Norway, among others. The magnitude and impact of these pledges will depend on the clarity of TFFF’s governance, effective inclusion of land and community rights, and alignment with other climate finance mechanisms.

Countries representing the Global South through groups such as BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, India, China) and the Like‑Minded Developing Countries (LMDC) emphasised equity, climate justice, common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR), and the need for developed countries to fulfil historical obligations.

Further, initiatives such as the Catalytic Capital for the Agriculture Transition (CCAT) fund were launched to restore degraded land with a US$50 million founding commitment. The fund aims to provide financial tools to help farmers in Brazil transition to more productive and sustainable practices while addressing deforestation. However, meaningful transformation will depend on moving beyond pilot investments and scaling efforts across the region, supported by robust monitoring mechanisms and the effective integration of smallholder farmers into the transition process.

India played an active role in shaping the key outcomes at Belém. Countries representing the Global South through groups such as BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, India, China) and the Like‑Minded Developing Countries (LMDC) emphasised equity, climate justice, common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR), and the need for developed countries to fulfil historical obligations. They reinforced the normative centrality of CBDR, protected domestic development priorities, and insisted that new mechanisms—such as those on just transition, finance, and nature‑based solutions—be operationalised in ways that do not shift additional burdens onto developing countries.

A Transition Deferred, Not Defined

Perhaps the most telling omission from COP30 was the absence of a clear, time-bound roadmap to exit fossil fuels, despite support from more than 80 countries. For many developing economies, the challenge is not ideological resistance but structural constraint: energy transitions require affordable finance, access to clean technologies, and policy space. Without these, calls for a rapid fossil fuel phase-out risk becoming another form of unequal burden-shifting.

In response, Colombia and the Netherlands announced plans to co-host the first “International Conference on the Just Transition Away from Fossil Fuels” in Colombia in April 2026, signalling a separate commitment through voluntary pathways.

Perhaps the most telling omission from COP30 was the absence of a clear, time-bound roadmap to exit fossil fuels, despite support from more than 80 countries.

Equally concerning was the continued gap in Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). The Paris Agreement (Article 4, paragraph 2) encourages each Party to develop, communicate, and maintain NDCs that it intends to achieve, promoting transparency and accountability in climate action. Since emissions trajectories are ultimately shaped by national and sub-national actions, delays or weak commitments significantly undermine global targets. In contrast, just ahead of the opening of the COP30 summit, the European Union confirmed its updated NDC, committing to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 66.25-72.5 percent by 2035 compared to 1990 levels. This pledge is anchored in its newly adopted 2040 target of a 90 percent net reduction in GHG emissions, marking a clear pathway toward climate neutrality by 2050.

In essence, COP30 called for a pivotal shift—towards accelerating implementation, scaling finance, and advancing equity. With robust delivery mechanisms and fair responsibility-sharing, global climate governance can move beyond inspiring declarations to deliver tangible impact.

Rajeev Kumar Jha is Director of Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) and Climate Change Adaptation (CCA) at Humanitarian Aid International (HAI).

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.