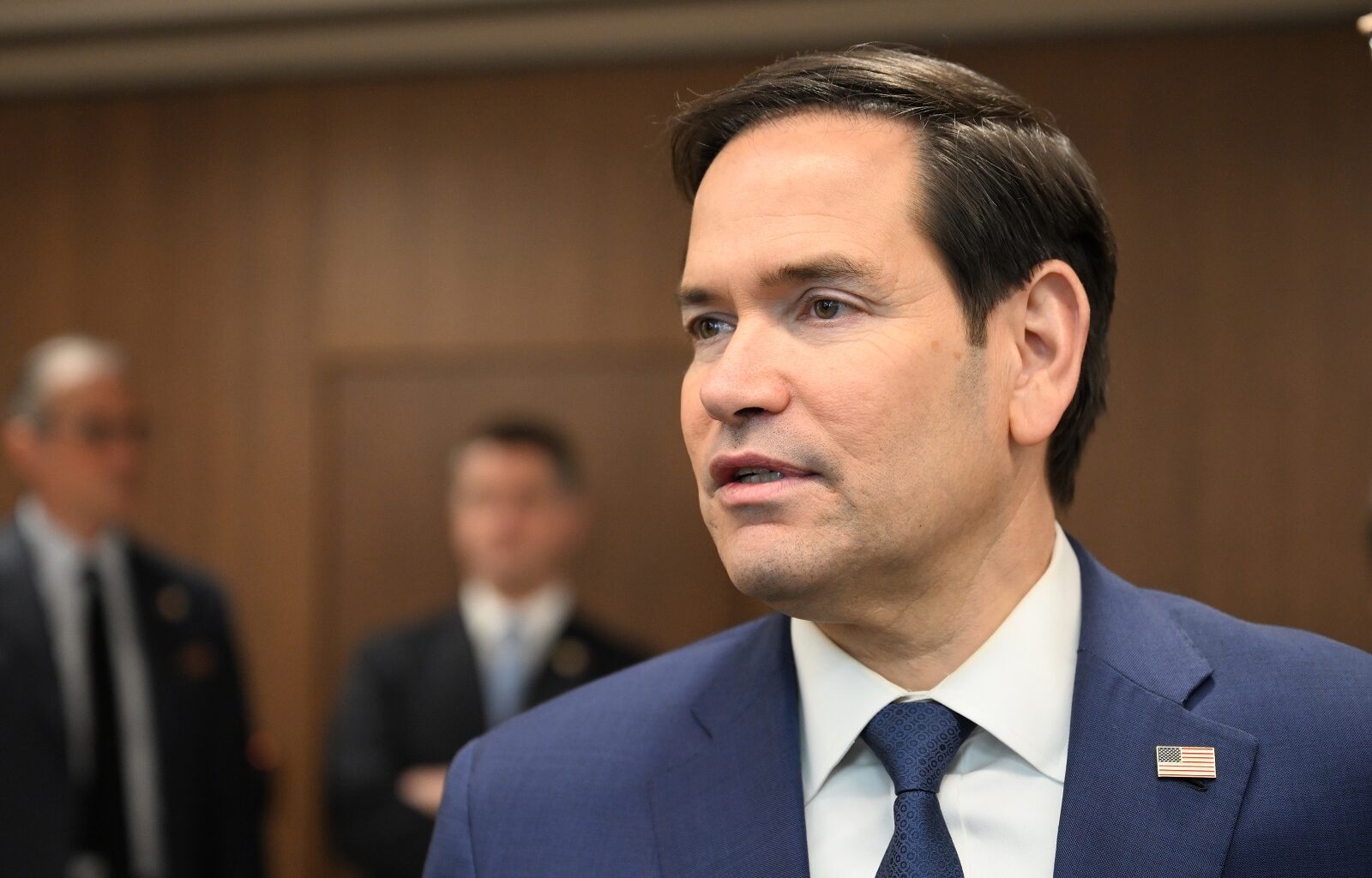

U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio described Colombia’s Petro as “an example of democracy,” despite their profound differences. Credit: U.S. Embassy Jerusalem, CC BY 2.0 / Wikimedia.

During an address by U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio in the United States Senate, regarding the situation in Venezuela and the Trump administration’s ambitions for the Caribbean country, the head of U.S. diplomacy spoke about Colombian President Gustavo Petro, citing him as an example of democracy.

Rubio’s words surprised observers in Washington and Bogota due to the long history of disagreements between the two governments over the past year. The statement came in a context marked by debates over U.S. policy toward Latin America and the Venezuelan crisis, issues that dominated the official’s testimony before lawmakers.

The political gesture takes on relevance because it comes after months of diplomatic friction, exchanged statements, and public differences between Washington and Colombia’s presidency. The reference to Petro as a democratic example contrasts with previous criticism from Rubio himself, raising questions about the real scope of the message and its impact on the bilateral relationship, one week before the meeting between Petro and Trump at the White House.

Marco Rubio cites Colombia’s Petro as an example of democracy in US Senate

Rubio appeared before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee amid a geopolitical landscape dominated by the situation in Venezuela, following the U.S. operation that led to the capture of former president Nicolas Maduro. During the session, he defended Washington’s strategy aimed at promoting democratic elections and internal reconciliation processes in that country.

The secretary of state stressed the importance of political systems that allow plural participation and representation of all social sectors, as part of the U.S. objective of promoting transitions toward democracies considered legitimate.

In addition, the head of U.S. diplomacy ruled out for now that the United States has further military operations planned on Venezuelan soil, although he did not rule them out if the new administration of Delcy Rodriguez does not cooperate with his government. The truth is that, beyond the populist rhetoric of Rodriguez and the rest of the Bolivarian regime’s leadership, the attitude shown by the current Venezuelan government maintains the complicated balance between rejecting external interventionism and cooperating with Washington.

It was in that scenario that Rubio mentioned the Colombian case to illustrate his argument about democracy. According to press reports, he highlighted that Petro, despite maintaining critical positions toward Washington, represents an example of how a democratically elected leader can express disagreements with the United States without breaking institutional frameworks.

Secretary Rubio’s speech yesterday in the Senate focused on the immediate future in Venezuela and relations with Delcy Rodriguez’s government. Credit: Iliana Rosales, Public Domain.

‘He doesn’t always speak well of us’

The U.S. secretary of state’s comment included a phrase that summarizes the ambivalence of the message. Rubio acknowledged that the Colombian president “doesn’t always speak well of us,” but still presented him as a democratic reference before senators, in what analysts interpret as an attempt to separate political tensions from the assessment of Colombia’s institutional system.

“We do not dispute that Petro is the legitimately elected president of Colombia and, nevertheless, he does not always speak well of us,” were his exact words in the Senate. The statement suggests a relevant nuance in the U.S. narrative about Colombia.

Instead of focusing the debate on ideological differences, Rubio seemed to prioritize the fact that the Colombian president was elected through a democratic process and maintains his institutional legitimacy, something he had not done until now.

For Washington, the message could also be aimed at other countries in the region, especially those involved in debates over electoral legitimacy and governance, at a time when the United States insists that the way out of political crises must involve transparent elections and plural political participation.

The positive reference contrasts with recent episodes of strong verbal confrontation between the two governments. In 2025, Rubio had openly questioned Petro’s political leadership on issues such as the fight against drug trafficking and bilateral security cooperation, pointing out that the problem was not institutional but rather one of political leadership.

On other occasions, the U.S. official went as far as to state that the strategic relationship with Colombia could not depend on what he described as the personal attitudes of the Colombian president, insisting that the alliance between the two countries is historic and transcends the governments of the day.

For his part, Petro has responded at different times with strongly sovereignist speeches, rejecting external pressure and defending the country’s political autonomy vis-à-vis Washington.

Next Tuesday’s meeting in Washington between Gustavo Petro and Donald Trump will shape the future of relations between the two countries, following a year of disagreements and growing threats. Credit: Joel Gonzalez / Presidency of Colombia.

The ambivalent approach of the Trump administration

Beyond the bilateral relationship, the mention of Petro can be interpreted as part of a broader discourse on U.S. foreign policy toward Latin America, reinforcing the ambivalent approach of the Trump administration during the first year of this second term.

Rubio’s appearance was marked by an emphasis on democratic transition processes and political reconciliation in countries in crisis, particularly Venezuela. In that sense, citing Colombia as a functional example of democracy — even with political tensions with Washington — can be read as an attempt by the United States to facilitate the dialogue that Petro and Trump will hold next week in Washington.

The relationship between Bogota and Washington continues to be marked by interdependence in issues of security, drug trafficking, trade, and migration, making structural deterioration unlikely despite rhetorical clashes.

From the meeting between the Colombian and U.S. presidents, the framework agreement for relations among the countries of the Americas is expected to emerge in the coming days, especially with those that have governments that publicly disagree with decisions made by the White House.

Both Bogota and Washington appear — at least a priori — to be willing to put their diplomatic capabilities on the table to achieve a complicated agreement capable of easing relations that have done nothing but deteriorate over the past year.