James Russ and Joseph Parker, the former and current presidents of the Round Valley Indian Tribes, are seeking to make their reservation healthy again.

That means helping their people, they say, and specifically tackling high rates of diabetes and obesity that affect their tribal nation and many other Indigenous communities.

It also means restoring their land and the river that has been intrinsically linked with their people for millennia.

“We are Native people tied to the resources and rhythms of the Eel River,” Parker said. “Our health is connected to the river.”

Now, the tribal nation is confronting the Trump administration over the river’s future and fighting some of its regional allies to reclaim water rights that have been overlooked for a century.

Members of the Round Valley Indian Tribe participate the the 15th annual 100-mile Nome Cult Trail near Anthony Peak in the Mendocino National Forest. (Kent Porter / The Press Democrat)

Members of the Round Valley Indian Tribe participate the the 15th annual 100-mile Nome Cult Trail near Anthony Peak in the Mendocino National Forest. (Kent Porter / The Press Democrat)

The struggle is taking place as the entity with a dominant stake in the river for generations, Pacific Gas & Electric Co., seeks to give up in Lake and Mendocino counties its network of Eel River dams and a linked hydropower plant. The move has triggered a federal review that has pitted the tribes, together with environmental groups in favor of dam removal, against farming interests, reservoir supporters and the Trump administration, which has taken a dim view of dam demolition.

The tribes never had much of a say when those dams went up starting 118 years ago, but they have been heavily involved in talks in recent years geared to planning for the future of the Eel River. Due to a century-old diversion that links the Eel River to the Russian River in the south — and to farms and about 100,000 residents who rely on the upper Russian for drinking and irrigation supplies — those talks have drawn in a host of sometimes competing interests, including counties and farm and fishery groups with a wider scope of interest across the North Coast.

Our “water rights were completely ignored,” Parker said of his ancestors. “The Round Valley Indian Tribes were very much in survival mode when the dams were built and the diversions began.

“It started in 1905 when W.W. Van Arsdale posted a note along a tree saying he had a right to appropriate more than 100,000 acre-feet of Eel River water to put into the Russian River basin,” Parker said. “That’s how it all started.”

PG&E has informed federal officials it wants to decommission Scott and Cape Horn dams and give up the aging, associated hydropower plant, offline since 2021, that has helped get Eel River water through Mendocino County’s Potter Valley into the Russian River basin.

In 2022, the power company applied to surrender its operating license to the Federal Energy Regulation Commission, which oversees the nation’s hydropower projects. The utility giant followed through with formal plans to FERC in June 2025.

Historically, FERC has had the final say and has not stood in the way of dam removal, though Congress and the White House have.

Years from now, the tribes and their allies hope their efforts will lead to the nation’s next big dam removal project, freeing the headwaters of California’s third longest river to revive its beleaguered salmon and steelhead trout runs — and the culture and economy of the Round Valley Indian Tribes, said John Bezdek, an attorney for the seven-tribe nation.

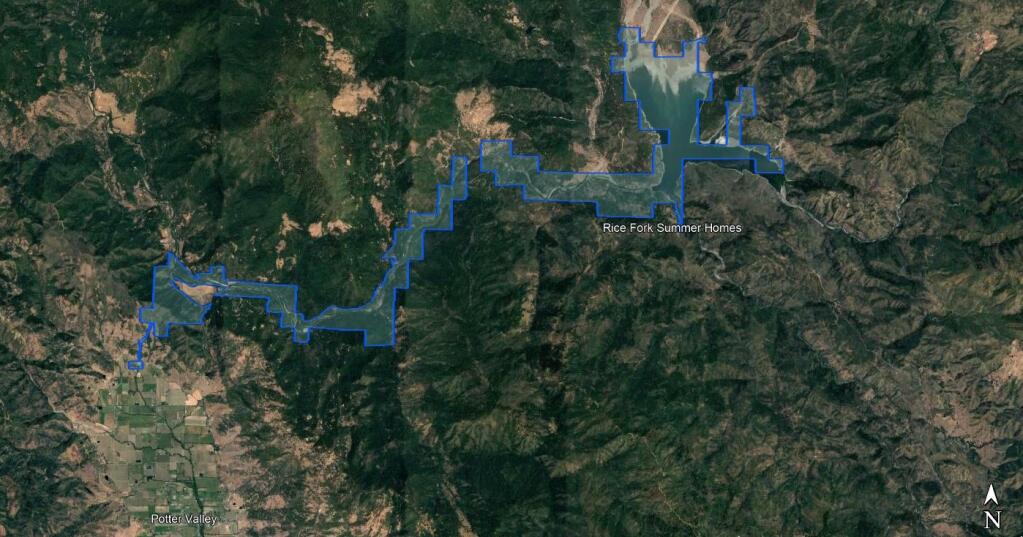

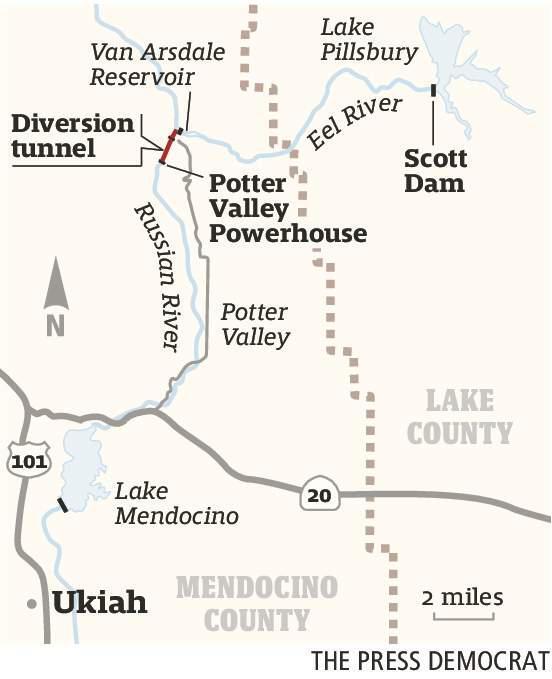

The Press Democrat

This map shows the location of Scott Dam, impounding Lake Pillsbury, and Cape Horn Dam, creating Van Arsdale Reservoir, on the Eel River, the Potter Valley power plant, and the diversion tunnel that feeds the powerhouse and supplements flows in the East Fork of the Russian River. (The Press Democrat)

“The fishery declined with the significant diversions of water into the watershed,” Bezdek said. “It was a source of subsistence and culture. This is a fishing tribe. That was taken away from them.”

Farming interests and others in the region, however, are against dam removal, pointing to downstream ripples for irrigators and drinking water customers, the loss of reservoir water for aerial fire suppression and the blow to the hundreds of Lake County residents and visitors around the largest of those reservoirs, Lake Pillsbury, a destination for boaters and hunters.

They secured a powerful ally late last year in the Trump administration, which raised its objections to dam regulators in a Dec. 19 letter from Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins. She warned that “if this plan goes through as proposed, it will devastate hundreds of family farms and wipe out more than a century of agricultural tradition in Potter Valley. Without it, crops fail, businesses close and rural communities crumble.”

Rollins also said that her department would work with the Department of the Interior to bring “real solutions” for water security to the North Coast.

The Round Valley tribes responded Jan. 14 in a letter to those two agencies, spotlighting a familiar slight: Rollins’ failure to acknowledge or even mention the tribes’ “senior water and fishing rights, much less our culture, our economy and our way of life.”

“We are reminding the departments … that the discussions going back to DC have been one sided and that we have been left out of the conversation,” Parker said in an interview with The Press Democrat.

Tribes to DC: Respect local solution

Just as dam removal opponents, including Lake County itself, are lobbying the administration to intervene and block federal sign-off on PG&E’s plans, the tribes and their allies are asking Washington, D.C., to allow a locally brokered water pact to proceed.

Known as the two-basin solution, it solidified a 30-year framework under which diversions from the Eel River to the Russian River would continue after dam removal, at least in periods of high flows, and only if there’s enough water in the Eel to support its salmon and steelhead runs. The pact supporters, including many local governments and water providers, agreed to construct a new diversion facility to support those operations, and to return water rights to Round Valley Indian Tribes who, as the first people in the area, have seniority rights to Eel River flows.

Hailed by supporters as historic when it was finalized in early 2025, the deal sought to rectify wrongs that disadvantaged tribes and harmed Eel River fisheries, signatories said.

“Our tribal members work and live in the broader regional community and despite the historic injustice to our tribal community, an ‘all or nothing approach’ is simply not realistic,” Parker wrote to the secretaries.

Parker and Russ said it was better to come together with partners and collaborate on a solution.

“We decided at the time we could spend the next 20 years arguing about what’s right and what’s wrong,” Russ said. “We decided collectively to focus on our commonalities so that maybe our kids and grandkids wouldn’t be fighting this war. We started to figure out what would be beneficial for everyone.”

But the deal has many staunch opponents, and few more visible these days than Cloverdale Vice Mayor Todd Lands, who has made his opposition to the pact and to dam removal a central part of his campaign for a seat on the Sonoma County Board of Supervisors. In January, he accompanied Secretary Rollins at an American Farm Bureau Federation conference in Anaheim, speaking out against the two-basin solution and appealing to the Trump administration to intervene.

“The two-basin solution does not guarantee water,” Lands told The Press Democrat. He fears the change from year-round to seasonal diversions will not be enough to fill Lake Mendocino, which helps sustain dry-season flows in the upper Russian River, the main source of drinking water for communities stretching from Ukiah to Healdsburg.

“This will cause drought conditions, not allow cities to replenish their water systems for fire and public use, and cause disease in the (Russian) river basin,” Lands said. “People will have to decide between showers and laundry and will not be able to have their own gardens as a food source.”

He also echoed shared concerns among dam removal opponents that the Round Valley Indian Tribes would cease all diversions “if the goals of the water supply and fish in the Eel River are not met.”

Those fears were inflamed in December when a California-based attorney for the Round Valley Indian Tribes told a group of Potter Valley farmers that diversions would one day end — comments that were caught on video and circulated widely.

In an interview with The Press Democrat, Bezdek, the tribal attorney based in Washington, D.C., sought to clarify that statement.

“Obviously if the fishery doesn’t recover, that will be a problem for us,” he said. “But we believe the best science is available and it says that we can do this.”

Parker and Russ elaborated.

“We believe everything is integrated,” Russ said. “The other side is saying we are putting fish before people. But we need healthy fish for a healthy balance for people. We are trying to create a healthy ecosystem for healthy people.”

Critical resource over millennia

The Round Valley coalition, made up of the Yuki, Pit River, Little Lake, Pomo, Nomlacki, Concow and Wailacki tribes, trace their ancestry in the area to “the beginning of time,” Bezdek said.

The Eel River and its tributaries served as the center of Indigenous culture, religion and trade.

The Eel River east of Potter Valley is summertime slow and lazy creating a spot for day use with water backed up by the Van Arsdale Reservoir at the Cape Horn Dam, Friday, June 7, 2024. (Kent Porter / The Press Democrat) 2024

The Eel River east of Potter Valley is summertime slow and lazy creating a spot for day use with water backed up by the Van Arsdale Reservoir at the Cape Horn Dam, Friday, June 7, 2024. (Kent Porter / The Press Democrat) 2024

“Our elders used to tell us stories about seeing so many fish that you could walk on their backs,” Bezek said. “Now, when we fish, we barely see a fish. Our ecosystem has just been decimated.”

As they told Rollins and Interior Secretary Doug Burgum in their Jan. 14 letter, the tribal nation seeks to bring back the health of the river and their community.

“If the river is not healthy, the community is not healthy,” Russ said.

Alexandra Hootnick/The New York Times

The Round Valley Indian Tribes Tribal Administration Building in Colveo, Calif., on Oct. 22, 2021. The confederation is made up of seven tribes, including the Yuki. (Alexandra Hootnick/The New York Times)

Sonoma County Supervisor David Rabbitt, who has close ties to the region’s farming industry, has heard the concerns of those opposed to dam removal, including their fears the tribe will end all diversions.

He isn’t buying that claim.

“There’s no automatic termination and no single entity can end diversions,” Rabbitt said. “The whole thing is a collaborative effort.”

Rabbitt, who read the Round Valley Indian Tribes’ letter, said he supported their effort “to set the record straight” and “establish a position within all the noise that’s going on. That’s vitally important.”

At the same time, he understood people’s fears and reservations.

“I will admit, I’m not a huge fan of taking down dams, but ultimately it isn’t my decision,” he said. “But then it’s ‘OK, what happens if you’re on your soapbox in the corner, it comes down and there’s no agreement for diversion? Then what?’

“We have to move forward.”

Rabbit is board president of the entity created by the pact outlining a post-dam future, the Eel-Russian Project Authority. Its aim for fish, he said, is “making sure both runs” — the Eel’s and the Russian’s — “are healthy. Our goal is to keep the diversion active and to do it in a responsible, collaborative way.”

Parker said collaboration is key and he shared his hope the Trump administration will work with the tribes and Eel-Russian Project Authority.

A spokesperson for the Department of Agriculture said it had received the tribes’ letter and “looks forward to formally responding to President Parker on this important topic.” The Department of the Interior declined to comment.

Bezdek said both secretaries have reached back out to him and are trying to coordinate dates to discuss a way forward.

“We were here before Sonoma County and Mendocino County and we will be here after they are gone,” Parker said. “PG&E’s decision to decommission the project is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to bring fairness. We know we won’t be adequately compensated, but the two-basin solution is the first step to heal those wounds and remedy this historical wrong.”

Staff Writer Phil Barber contributed to this story.

Amie Windsor is the Community Journalism Team Lead with The Press Democrat. She can be reached at amie.windsor@pressdemocrat.com or 707-521-5218