Set out north from Fort Worth, Texas, and you rapidly leave the built-up centre of town behind and enter a sprawling low-rise world of warehouses, bungalows, retail outlets and curved slip roads sliding off the interstate. Look over to your left after about twenty minutes’ drive and you’ll see a two-storey white-fronted structure gleaming unusually brightly in an unusually large lot. This is one of the most profitable single buildings in the world so security is tight, but it does welcome visitors. On the day I came, an electronic voice at the front gate greeted new arrivals (“Howdy, y’all!”), and instructed us to leave prohibited items in our vehicles. An articulated golf cart waited outside to give me a lift. It could have carried perhaps sixty people, but it held only me.

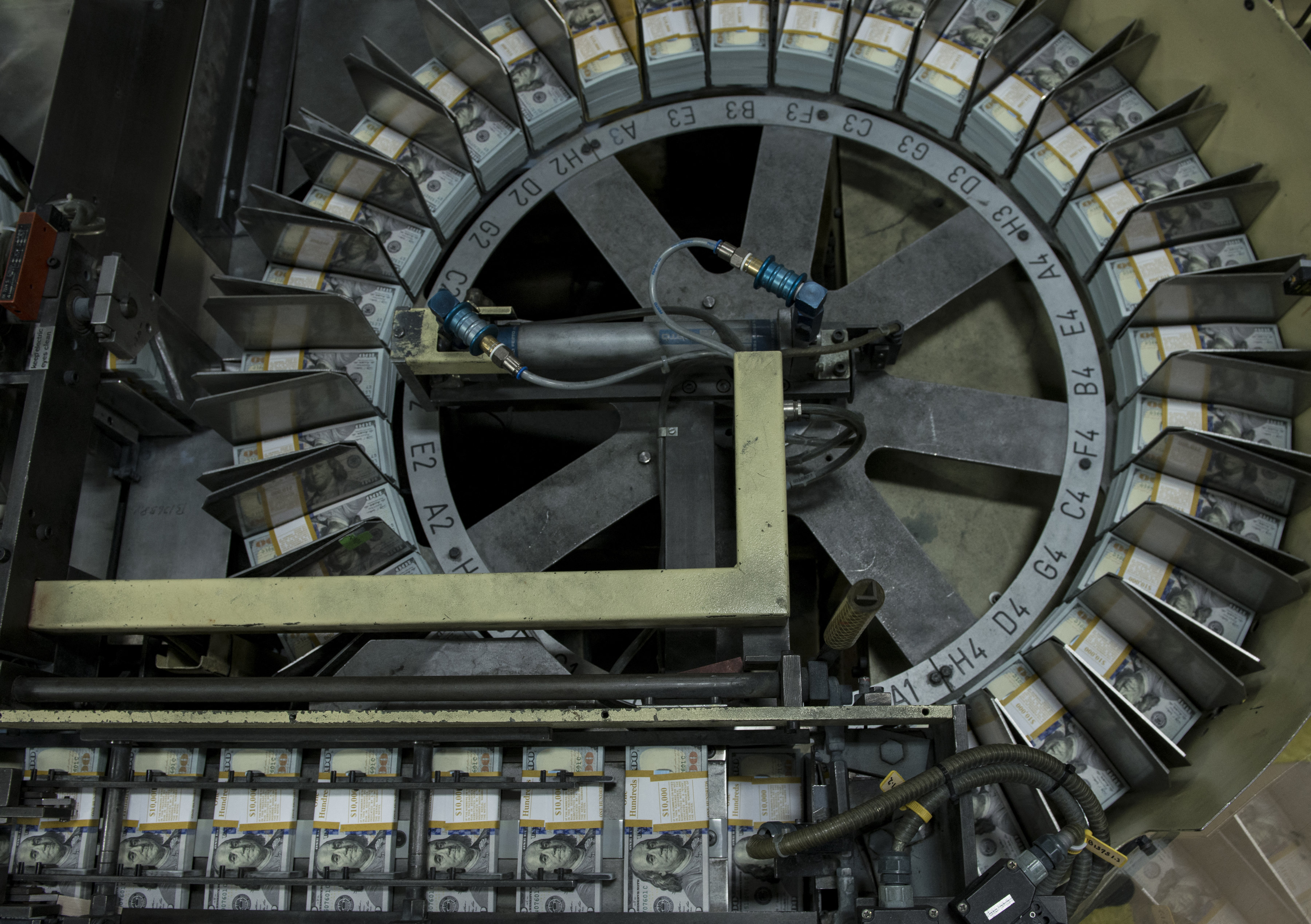

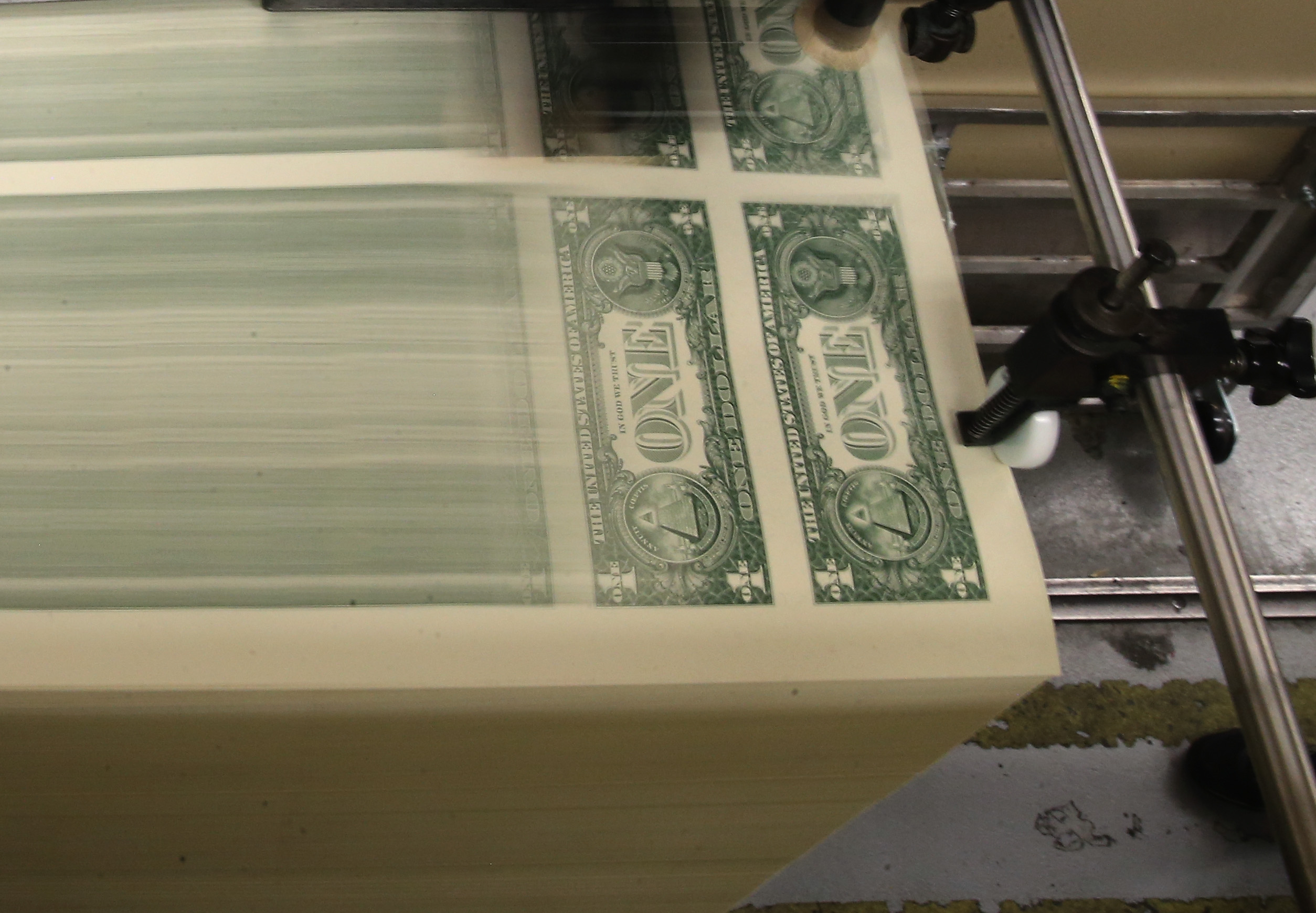

Since December 1990, when it opened, the Western Currency Facility has been where the Federal Reserve’s Bureau of Engraving and Printing (BEP) has printed most of America’s dollars (if “FW” is printed in small letters in the corner of a banknote, it came from Fort Worth). In 2023 more than 5.7 billion banknotes rolled off the presses in the two BEP facilities (there is a smaller, older one in Washington). That is 182 per second, 656,000 per hour or 15.7 million a day — all day, every day. “It’s a great job because you get paid good money to make money,” said one BEP worker in a promotional video that I watched all alone in the site’s little movie theatre. “Let’s Make Some Dough”, a large sign declared. “The Buck Starts Here”, another said. Most of the employees were middle-aged men but a woman with blonde hair in a scrunchie was using a jack to move a pallet of banknotes. Its contents were worth perhaps $64 million (£47 million). The vibe was friendly and proud. They were doing a fine job, so please don’t think I’m including them in the criticism that’s about to come. Because something weird was happening here.

I travelled to Texas by plane from London and I arrived in Fort Worth on a bus. I booked the taxi to the BEP facility via the Lyft app. I stayed in accommodation I booked on Airbnb and I ate at restaurants and cafés. I paid for all of that with a debit card. In fact, during my stay in the Lone Star state pretty much the only time I used physical currency was to leave tips for waiters. In this I wasn’t unusual. Surveys show that people in the US use cash less and less each year. Two fifths of Americans use no cash at all in an average week, up from a third a decade ago, and when people do use cash the transactions they use it for are getting smaller. This all makes perfect sense: you can’t use cash to shop on Amazon or eBay. Why bother going to an ATM to take out cash to pay back a friend when you can just transfer funds to them via Venmo? This is not just convenient, it’s safe too. Credit card transactions are protected from fraud, and you can’t be robbed of your cash if you’re not carrying any.

This is not solely an American phenomenon. In pretty much every country on earth, cash is being quickly or slowly outcompeted by electronic payment methods. Some countries — Germany and Austria, for example — are more attached to cash than others, but even in those outliers the share of transactions made with physical money is falling all the time. In the UK in 2024, according to UK Finance, which represents the country’s banks, just 9 per cent of payments were made with cash, down from more than half of transactions a decade earlier. Almost half the British population now uses cash just once a month, or not at all.

• Can cryptocurrencies come back from a rollercoaster year?

So why are the BEP facilities in Fort Worth and Washington so busy? They are of course replacing worn-out bills that can’t be used any more, but they are also continuously increasing the number of banknotes in existence. In November last year the value of all the dollar bills in circulation hit a new all-time high of $2.422 trillion (it hits new highs every month, so may well have done so again before you read this), which is almost exactly double the total a decade earlier, and that was in turn almost exactly double the total a decade before that. In fact the total value of notes in circulation, as reported by the Fed, has been doubling every decade for as long as I’ve been alive.

For euros, the picture is similar. The most recent figure for the total circulating value of the European Union’s single currency is €1.619 trillion (£1.2 trillion), which is also an all-time high, and also significantly higher than the €1.083 trillion of December 2015 and the €565 billion of a decade before that. The same pattern of remarkable increase is true, if not quite so dramatically, for British pounds, Japanese yen, Australian, Canadian, Singaporean and Hong Kong dollars, Swiss francs and most other currencies.

The Federal Reserve’s two complexes in Fort Worth, above, and Washington printed more than 5.7 billion banknotes in 2023 — or 182 a second

GETTY IMAGES

Sheets of $100 bills are readied for inspection at the Western Currency Facility in Fort Worth, Texas

GETTY IMAGES

Sheets of one dollar bills run through the printing press at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in Washington, DC.

GETTY IMAGES

To meet this demand, currency printers are investing in extra facilities. New printing presses in Fort Worth can fit 50 banknotes on a single sheet instead of 32, to increase the facility’s output. And the BEP is also building a whole new 920,000 sq ft factory in Beltsville, Maryland, due to open in 2031. So cash hasn’t died out. It is instead being produced in such vast quantities that whole new factories are required to meet demand. In this, central banks are just doing their job. Governments have tasked them with producing cash “elastically”, which is to say that if citizens demand banknotes, central banks need to print them.

The thing is, though, that ordinary citizens are not demanding banknotes. Ordinary citizens of the United States, Great Britain, the European Union, Australia, Canada, Switzerland and many other countries are using banknotes less and less, yet more and more of them are being printed. So where is the demand coming from? Where on earth are the banknotes going? Who’s spending them? What are they buying?

It was Andrew Bailey, now governor of the Bank of England but in 2009 its chief cashier, who first noticed something strange was going on. His job gave him oversight of the UK’s banknotes and coins, and it was in this capacity that he made a conference speech in Washington about what he called the “paradox of banknotes”: the ever-increasing value of cash in circulation, set against its ever-decreasing use for buying things. “This may come as something of a surprise to the ‘cash is dead’ lobby,” he said.

The Bank of England argues that there is general demand for new banknotes, driven partly by fundamental changes to society, including a rising population, inflation and economic growth, but also by low interest rates (which incentivise people to hoard cash at home), frugality (cash is a useful budgeting tool) and pessimism (people like having cash in case of an emergency). The Bank also notes that “some cash may be used in the shadow economy, where activity is unrecorded and may be illegal”.

The last part of that explanation deserves a lot more scrutiny.

The Bank of England governor, Andrew Bailey, in July last year. He described the ‘paradox of banknotes’ in 2009

REUTERS

As long ago as 1976 a McKinsey consultant named James Henry noticed how odd it was that — in an age when more and more people were using cheques — cash demand remained so healthy. “There are only two kinds of activity in the US which depend almost exclusively upon large, untraceable, non-credit transactions,” he wrote in Washington Monthly. “The first is profit-motivated crime: illegal gambling, drugs, prostitution, loan sharking, protection, etc. The second is tax evasion.”

It’s a point so obviously true that it’s a wonder he had to make it. Yet central bankers are still struggling to accept its implications.

Economists say that money has three functions. As a unit of account, it allows people to tot up the value of their trades so they can value, say, pigs and shovels in a commonly agreed manner rather than trying to work out the exchange rate between them. As a medium of exchange, you can bring cash to the market and swap it for a pig or a shovel. And as a store of value, once you’ve sold a pig or a shovel, you can take your money home and stick it under a mattress.

• Are we facing an emergency cash crisis?

This is the framework through which Bailey and subsequent central bankers —with one notable exception, as we will see — have viewed the paradox he identified, and the general discussion has gone like this: we can see that cash money’s use as a medium of exchange (function No 2) is declining, yet demand for cash money increases all the time. If it’s not being used as a medium of exchange it must of necessity be being used as a store of value (function No 3). If people aren’t using cash to buy pigs or shovels any more, they must be shoving it under their mattresses.

This is not the full picture, though. Central bank surveys show that the amount of cash their respondents are storing at home makes up only a tiny fraction of the amount they’re printing. In 2022 the average American held $418 in cash money in reserve, which is quite a lot, but nothing compared with the $7,357 outstanding for every person in the United States. That’s almost $7,000 missing for every man, woman and child in the country. In the eurozone the total of cash outstanding is almost €4,500 for every resident, which is excessive even for cash-enthusiastic countries such as Malta or Cyprus; in the UK it’s about £1,200, which is seven times more than Bank of England surveys show Brits are holding. Central bankers deal with this puzzling discrepancy by basically ignoring it, which is a shame because within it is a second paradox that helps explain the first.

Surveys show that where cash is still being used, it tends to be for small transactions: to leave a tip, to pay for a bus ticket. The vast majority of people don’t buy expensive things with banknotes any more, and in fact in some countries it is now illegal to do so. As such, you would expect the banknotes in circulation to skew towards the smallest denominations, the kind of notes that are useful if you’re buying a coffee. There should therefore be far more dollar bills in existence than $100 bills, far more fivers than £20 notes, and more €10 notes than €200s. Yet not only is the opposite true, but the opposite is becoming ever more true with each passing year.

Two decades ago the $100 bill was only the third most common banknote in circulation, but it overtook the $20 at some point in 2008 and then the dollar bill eight years later. Today there are more than 18 billion of them in circulation, 55 for every American. In raw value terms, about 80 per cent of all the paper dollars out there are made up of $100 bills, yet how often does anyone encounter one?

There is a similar dynamic with euro banknotes. Some 690 billion — almost half — of the euros in circulation are in the form of €100, €200 or €500 notes. The biggest denominations are also popular in Britain, Australia and Canada, while more than 90 per cent of all Swiss francs in circulation by value are in the form of the 1,000 franc note, worth more than $1,200, which is one of the most valuable banknotes in existence.

There is thus not one question but two: why are so many more banknotes being printed, when ordinary people are using less cash? And why are most of those banknotes of the largest denominations, when ordinary people only use the smallest ones?

Bryan Cranston delves into the secrets of money laundering in Breaking Bad (2008)

ALAMY

The Federal Reserve did arrange an off-the-record briefing for me with one of their economists about what was happening to all this cash, but it wasn’t very helpful. “The difficulty of the problem is it’s hard to know where it goes,” he replied.

I asked whether it might be in the hands of criminals. “I imagine that would be something where the Justice Department would be more involved.”

Fortunately, however, central bankers are not the only people who analyse the use of cash.

There are also police officers, and the story they tell could not be more different. Back in 1994 a conference in Washington discussed the spread of organised criminal gangs around the world. Officials from US and international enforcement agencies analysed connections between Russian gangsters, South American cartels, the Italian mafia and others.

Speakers fretted that criminals might one day create a giant interconnected underworld, a transnational corporation of crime enabled by shell companies, crooked lawyers and secretive banks. But David Veness, then the assistant commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, brought the discussion down to earth. “Untraceable, untaxable income in the hands of criminals is the new lingua franca of organised crime,” he said. “The link between Medellin and Moscow is the $100 bill.” Don’t get distracted by fancy innovations, in other words — the world might be changing but cash is still the criminal’s best friend.

Another British policeman, Rob Wainwright, had his name on a 2015 report by Europol — the European Union’s agency for law enforcement co-operation — asking the question the central banks have avoided: “Why is cash still king?”

Five years later he spoke about the report to a Canadian inquiry into money laundering: “As we were moving in the legitimate economy, to a more and more cashless society, the point we were making is this absolutely wasn’t the case — and, I believe, still today is largely not the case — in the crime world.”

The report contains photographs of cash being smuggled inside confectionery, in boxes of tampons, in electrical appliances, in the linings of suitcases and — via x-rays — inside people’s bodies.

These are images that expose the most obvious explanation for the popularity of large-denomination banknotes: you need fewer of them to move a lot of money. A million euros in €50 notes would fill a suitcase, but if you change it into €500 notes you could fit it in a laptop bag.

That’s why criminals will buy the biggest bills for more than their face value. A study by Harvard academics shows that, in countries as various as Myanmar, Ethiopia and Argentina, $100 bills attract an exchange rate up to 20 per cent higher than other cash dollars. When I moved to Russia in 1999 I was paid each month in cash dollars and always tried to get the big bills, since I knew I’d always get more roubles for them.

Cash talks for Ralph Bellamy, left, and Don Ameche in Trading Places (1983)

GETTY IMAGES

Criminals want cash dollars — or, to a slightly lesser extent, cash euros and pounds — so they can buy things without suspicious compliance officers being able to notice the transaction and report it to the authorities. Drug smugglers take payment in hard currency, as do people smugglers, wildlife traffickers, kleptocrats and terrorists — anyone who wishes to evade detection.

The production of €500 notes ceased in 2019 because of concerns that it “could facilitate illicit activities”. But for the most part, by making it so easy for criminals to obtain banknotes, western governments are making it profitable for them to commit crime.

US authorities estimate that about $25 billion in large-denomination bills is smuggled to Mexico every year, vacuum-packed and concealed in the structure of vehicles crossing the border. The biggest cash seizure ever was $207 million found in 2007 in Mexico City, but it is unusual for criminals to keep that much together in one place. Most shipments across the US–Mexican border contain between $150,000 and $500,000. Cash has been found hidden in the corrugations of cardboard boxes, rolled up in the middle of kitchen rolls, inside nappies, in the gearboxes of trucks, behind the insulation in the hulls of yachts, beneath cargoes of loose grain; if you can imagine it, criminals will have done it.

The money can then make its way back in the other direction.

Ever since Albanian gangs cornered the UK market in cocaine around 2016, the annual repatriation of cash pounds from Albania to the UK has increased from about £65 million a year to £400 million, much of which had been smuggled to Albania, then paid into a friendly bank branch far from the UK authorities before being sent back by the official route.

• Ministers crack down on dirty money

My hypothesis is simple: the reason that $100 bills are now the most popular notes being printed in Fort Worth is because criminals prefer them to anything smaller.

If the largest banknote was a $50, then criminals would need to either make twice as many trips to smuggle their wealth or risk transporting more value in each shipment; if the largest banknote was a $20, they would need to make five times as many shipments and the whole business model would fall apart. Central bankers’ lack of curiosity about this seems to be close to wilful blindness.

But this can’t be the whole story. If criminals were just moving their cash earnings to a place where they could wash it back into the formal financial system, then the number of banknotes in circulation would remain static, at least as a proportion of the economy, but that’s not what is happening. The number of banknotes is increasing, and the question of why the value of banknotes has increased so markedly remains unanswered.

This is where those central bank analyses — which concluded that if cash is no longer being used as a medium of exchange then it must be being used as a store of value —fail to take real life into account. A person with cash wondering whether or not to pay it into a bank doesn’t base their decision solely on the current rate of inflation, or the risk of the bank going bust, as the central bank papers assume they do.

For ordinary people there are far more pressing risks to your savings: being robbed; your house burning down; your husband getting drunk and spending your savings on vodka. All these are good reasons to get your money into a bank and out of harm’s way. Similarly there are good reasons to keep your money out of a bank, of which evading detection by the tax authorities and law enforcement agencies are obviously at the top of the list.

Phil Collins, centre, enjoys the spoils in Buster (1988)

ALAMY

To a central banker all money might look “fungible”, a word they use meaning interchangeable, but to an ordinary person electronic money and cash money are wildly different things. Money doesn’t only have the three functions that economists think it has, it has other functions too — anonymity, convenience, safety — and they change depending on what kind of money it is. And that brings us back to the one central bank analysis I mentioned above as an “exception”: the only one I found that grapples with the world as it is, rather than as economic theory says it should be.

I’m not going to pretend I understood everything that Janet Hua Jiang and Enchuan Shao wrote in their paper for the Bank of Canada in 2014. The bulk of its 38 pages features mathematical symbols I couldn’t even pronounce, let alone use. But their core insight is the key to the puzzle. When central banks say that the use of cash in the economy is declining, what they really mean is that the use of cash is declining in the bit of the economy they monitor, which is a very different thing. This paper separates out money’s function as a medium of exchange in the “cash-credit economy”, which is the bit where banknotes are being outcompeted by Venmo, Visa cards, Apple Pay, Revolut, Wise and all the rest of the technological innovations that have transformed how we pay for things, and its function in the “cash-only sector”, which is where banknotes remain dominant.

Central banks don’t see it because those transactions bypass the institutions they oversee, but the obvious implication is that if the value of banknotes in circulation is booming, the cash-only economy — the one where criminals are laundering money on an epic scale — must be booming too.

In 2016 Kenneth Rogoff, an economist at Harvard, published a book called The Curse of Cash, in which he argued that by printing so many dollars the US government is helping criminals, terrorists and tax dodgers to make the world poorer and less safe. Seeking to shift perceptions in the corridors of power, he even held a seminar in the Treasury Department to explain his point. “But they were, like, ‘Everybody loves our dollars,’ ” he told me. “They love us, everyone’s buying them —why would we want to stop selling something that’s so popular?”

© Oliver Bullough 2026. Extracted from Everybody Loves Our Dollars: How Money Laundering Won (Weidenfeld & Nicolson £25). To order a copy go to timesbookshop.co.uk. Free UK standard P&P on orders over £25. Special discount available for Times+ members