Contents

The Overarching Challenge and Response. 8

U.S. Policy Paradigm Shifts 11

The United States has been the world’s dominant techno-economic power for the last 125 years since it overtook the United Kingdom and Germany in the late 1800s. But in recent decades, while being the leader has been better than being a laggard, it also has induced complacency, much as the United Kingdom lost its grip on industrial leadership.

Based on extensive analysis, the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) predicts that China will soon surpass the United States in a broad array of what we term national power industries: advanced, traded-sector industries that are critical to economic strength and national security.[1] (See box 1.) Yet, policymakers in Washington so far have advanced only limited and cautious responses that fail to address the core challenge America faces from China.

Faced with the mounting evidence that America will soon be displaced as the global techno-economic power, policymakers, analysts, and advisers tend to respond in one of three ways. The first and the most common reaction is denial, claiming that the situation is not really that bad. China may be good in steel, consumer electronics, telecom equipment, clean energy, drones, electric vehicles, and high-speed rail, but that’s all. So, while America might need to tweak some of its policies and programs to stay ahead, our basic approaches to technological innovation and economic management will largely suffice as they are.

Policymakers in Washington so far have advanced only limited and cautious responses that fail to address the core challenge America faces from China.

Along similar lines, many claim that America will continue to lead because of its basic freedoms, its knack for innovation, its entrepreneurial culture, its research universities, and many other intangibles that constitute the American Way. Together, it is tempting to comfort ourselves assuming that these things are the essential ingredients of America’s success as a nation, and China can’t emulate them, so we are safe. But the reality is that, absent robust change, we will lose. America is increasingly hampered by structural weaknesses and self-inflicted wounds, including cuts in government research and development (R&D), limited STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) skills, corporate short termism, institutional resistance to change, rising anticorporate and antitech animus, alienation of core allies, resistance to competitiveness-focused industrial policy, massive budget deficits, political disfunction, and more. Meanwhile, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is hyper-focused on global preeminence, and it has enacted powerful comprehensive strategies to achieve that goal.

Given these realities, the second possible response to China’s challenge is to accede to being a second-tier power, as the UK did after World War II. In some ways, shedding the responsibilities of global leadership would be a relief. There would be no more need to police the world. We could even reembrace the Monroe Doctrine by withdrawing into a hemispheric cocoon behind tariff walls and two oceans. And if you are on the Left, there would be no more need to worry about the health of business and maintaining a good business climate; we could pursue regulatory and redistributive measures to achieve a post-capitalist Utopia. Unfortunately, this sort of gradual, if grudging, acceptance is most likely to be the order of the day, if for no other reason than inertia: There has been little evidence of political will to reverse America’s national decline.

There is, however, a third possible response to the China challenge: to vow that we will not allow America to lose this techno-economic-trade war without a putting up a fight, which requires making fundamental changes in the U.S. techno-industrial-economic system.

This report outlines the overall scope of the challenge and the fundamental policy change that will be required for America to avoid losing. Other reports in this series will lay out in greater detail new paradigms for specific U.S. policy realms, including corporate financing and investment, trade, science and research, manufacturing, social regulation, antitrust, and more.

Make no mistake: The policy changes required to avoid losing the techno-economic-trade war to China will be outside the Overton Window of options that Washington policy elites have traditionally deemed to be acceptable. In fact, few are even considering them. Moreover, the changes ITIF will propose in this series are sure to bring stiff opposition from incumbent and entrenched interests, as well as from ideologues from the Right and Left. Predicable reactions will be that we can’t afford to make major federal investments; dramatic change is not needed; it will make things worse, not better; bold, strategic intervention in U.S. innovation and economic systems would violate free markets; federal initiatives of that sort contravene states’ rights; it is un-American; and more.

The most important first step the United States can take is to recognize the dire nature of the challenge it faces and accept that it requires bold new approaches. Incrementalism will not cut it.

Furthermore, even if Washington can summon the political courage to take bold steps, America still will likely lose. Even with population decline, China’s workforce will remain massively larger than America’s for many decades. Even with budget challenges, China’s forced high savings rate will allow vastly more investment in national power industry development than the United States can muster. And as long as China remains a one-party authoritarian system, its overarching goal will be amassing national techno-economic power, not consumer or worker welfare. The reality is that the CCP’s juggernaut is powerful and insurmountable.

The PRC development juggernaut is set on global dominance of most advanced industries. It is too late to stop China from advancing most of its national power industries to be on par with global leaders, including both mature industries where China has in the past lagged behind (such as software, biopharmaceuticals, aerospace, fine chemicals, semiconductors and semiconductor equipment, and machine tools) and emerging industries where it aims to leapfrog the West (such as AI, quantum computing, and nuclear fusion). But it is not too late to stop the absolute erosion of U.S. and allied capabilities.

To do that, the overwhelming weight of evidence clearly shows that America and its allies must take bold action. Otherwise, they are certain to lose much of their core national economic power industry capabilities and the freedom of action and national security that comes with that. So, bold action is worth the risk. In fact, there is no better option.

And “bold” is the operative term. There was never an official declaration of techno-economic-trade war between China and the United States, but this war has nonetheless been underway for many years, and it has now reached a crisis point, such that reacting with incrementalism will fail. Given the pace at which China has gained ground on the United States, it would be irrational to assume that if we just do a bit more of what we have already been doing, all will be well. Examples of incrementalism would include expanding high-skill immigration and federal research spending by a bit, reforming regulations such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) to make them work just a bit better, passing piecemeal bills to address a few narrow issues here and there, and tweaking a few existing programs. Even if the federal government were to more than incrementally expand and improve the tools and mechanisms in the current U.S. techno-industrial-economic system, we would still lose. It just might extend the timeline by a few years.

The organizing principle and main objective for U.S. techno-economic-trade policy must be bolstering the competitiveness of our national power industries to confront the China challenge. That objective must take precedence over competing economic goals and principles.

As such, the most important first step the United States can take is to recognize the dire nature of the challenge it faces and accept that the situation requires bold new approaches in response. Incrementalism will not cut it. Doing so leads to a simple but far-reaching proposition: The organizing principle and main objective for U.S. (and allied) techno-economic-trade policy must be bolstering the competitiveness of our national power industries to confront the China challenge. That objective must take precedence over competing economic goals and principles such as allocative market efficiency or redistribution, and it should not be conflated with separate policy principles and priorities such as pursuing racial equity and social justice or addressing climate change. To avoid losing to China, America must put itself on a wartime footing when it comes to matters of technological innovation, economic competitiveness, and trade. That requires compartmentalizing other issues.

We say “avoid losing,” as opposed to winning, because China is a formidable competitor with a massive domestic market, beckoning opportunities internationally (e.g., in Belt-and-Road nations), and an enormous “bank account” to subsidize its way to global dominance. It is very likely that it will not be possible to keep Chinese firms from becoming leaders in many national power industries, especially in non-OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) markets. But nations in the West can and must avoid losing their own power industry capabilities. Doing so would put the CCP in the driver’s seat.

Box 1: National Power Industries

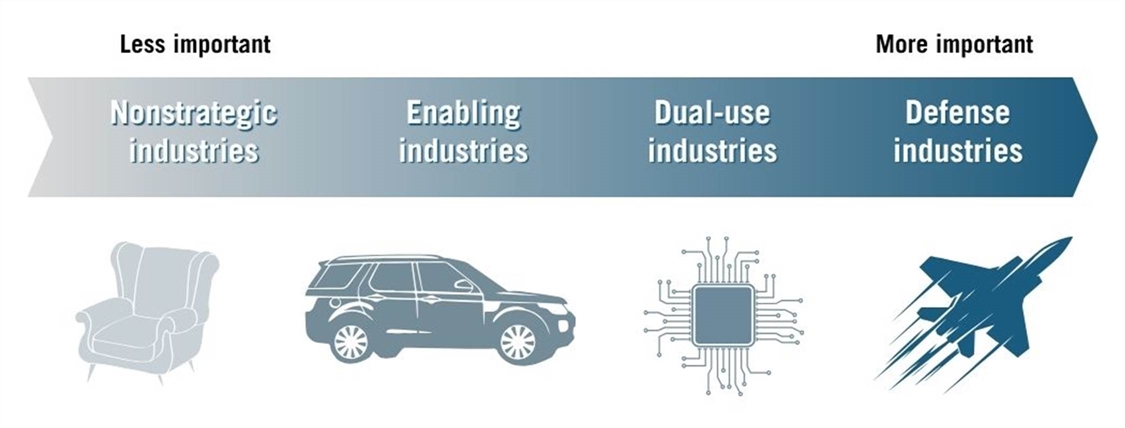

National power industries comprise not just any manufacturing industry, or even any technologically advanced industry. They can be thought of as three categories, from most important to least: military industries, dual-use industries, and enabling industries.[2]

Examples of military technologies and industries are guided missiles and tank production. Examples of dual-use technologies and industries are electronic displays and semiconductors, which are used for both defense and commercial purposes. Imagine, as a thought exercise, that China dominated optics and displays, which are used not just in AR/VR (augmented and virtual reality) headsets for gaming but also in headsets and upright displays for fighter jets. This would give China dangerous leverage over U.S. defense capabilities.

Meanwhile, enabling industries include component technologies and final products such as automobiles and heavy construction equipment, which contribute to the industrial commons that supports dual-use and defense industries.

Finally, there are industries such as furniture, cosmetics, sporting goods, wind turbines, wood products, and toys. These are not national power industries, in part because losing them would not create any serious vulnerabilities to China. Kids might not have many toys, but we can live with that. The same is true for virtually all nontraded sectors (e.g., barber shops, retail, personal service providers, etc.), which by definition are not subject to competition from foreign imports.

Figure 1: Industrial power scale

Because maintaining allied strength in national power industries is critical, policymakers must jettison the deeply held Panglossian view that governments should not pick winners and that market outcomes are the best of all possible worlds. Markets might optimize per-capita GDP growth (although even here, there are market failures that suggest some government intervention is needed to maximize per-capita GDP growth), but only by luck and happenstance will they generate needed power industry capabilities. There is no inherent reason why the United States or its allies will produce leading-edge telecom equipment, semiconductors, electronic displays, jet airplanes, drugs, circuit boards, and more, especially in the face of predatory Chinese competitors that are backed by a deep-pocketed and intently focused Marxist-Leninist state. Other sectors might prove much more profitable for investors.

Moreover, weakness in dual-use and enabling industries would critically undermine the U.S. defense sector, requiring federal defense budgets to be far larger than is otherwise necessary in order to produce weapons systems and everything else the military needs in specialized factories with limited economies of scale. Markets, for all their value, are happy to enable the production of financial advisors, legal services, and high-end garments and let dual-use sectors wither and die in the face of subsidized Chinese production. This is true even with a robust, generic national manufacturing strategy, which generates more production of shoes, golf clubs, and two-by-fours, but not optics, machine tools, or lasers that weapons systems need.

Policymakers understand this when it comes to the production of weapons such as fighter aircraft and guns. While private companies design and build those, they do so under government contracts. It’s time to extend that thinking to dual-use and enabling industries. These industries do not need to be supported by government contracts in most cases. But in all cases, there should be well-crafted and effectively implemented government programs to ensure continued dynamic capabilities in national power industries.

Markets, for all their value, are happy to enable the production of financial advisors, legal services, and high-end garments and let dual-use sectors wither and die in the face of subsidized Chinese production.

The implications of this are simple, yet profoundly important. It is time for the U.S. government to craft a coherent power industry strategy. This does not imply state socialism, cronyism, or corporate welfare; however, it does imply using government policy to help companies in national economic power industries to be successful globally, especially against Chinese companies.

In military affairs, threat assessment is critical. That’s why the Department of Defense (DOD) has an Office of Net Assessment. Similarly, threat assessment is critical in techno-economic-trade affairs—specifically, to assess threats to U.S. national power industries. Today that threat comes principally from the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

There are five key principles that should guide U.S. techno-economic-trade policy toward China:

1. China is an adversary of the United States and of Western democracies more generally. China is seeking to gain significant global market share in virtually all advanced industries that are critical to national power. And competition in these industries is win-lose: To the extent China gains global market share, allied nations lose. That process can and often does end in dominance on the Chinese side and market withdrawal on the allied side.

2. National power industry capabilities are so critical that losing them to China cannot be an option. To the extent that U.S. and Western losses grow, allied military strength weakens and PRC leverage over allied nations increases, putting them in a subservient position.

3. Strong domestic policy actions are necessary but not sufficient to avoid losing production capabilities in national power industries. China’s engine of techno-economic-trade mercantilism is so powerful, and allied nations operate with such significant natural limitations (political and budgetary), that domestic policy actions can only slow down losses, not reverse them, or even stop them. Doing that would require also limiting PRC firms’ access to a significant share of allied markets.

4. Just as domestic action alone is not sufficient to avoid losing the techno-economic-trade war to China, efforts that individual nations undertake on their own will not be sufficient. China is simply too big and now too rich for any individual country, even one the size of the United States or the European Union, to survive the battle on its own. The West must band together in a national power industry alliance.

5. Transforming techno-economic-trade policy on both the offensive and defense sides of the equation cannot be done incrementally. It requires launching a new system of “national power capitalism.” This will entail going back to “square one” in a host of policy areas—including business financing and governance, trade, education and training, science and technology, and market regulation—and redesigning to match the CCP challenge. At the same time, governments need to craft analytically based sector strategies for key national economic power industries.

This will be difficult politically, not least because there is little consensus on the nature of the challenge, but also because of longstanding commitments and deeply engrained biases in favor of particular policy solutions.

At the top of the list is the Trump administration’s approach to trade policy. While President Trump deserves significant credit for sounding the alarm about China in his first term, his current trade policy will not solve the problem. It does not distinguish between national power industries and other industries. It does not focus on China, but rather alienates most U.S. allies and potential allies, inadvertently driving them closer to China as we have just seen with Canada. Because it invites retaliation, it limits global market access for strategically important U.S. industries that require global scale for survival. And by placing high tariffs on many intermediate goods, it raises costs for many U.S.-based companies trying to sell final goods in global markets. The administration’s free-market ideology, coupled with resistance to raising taxes, also means that key proactive advanced industry policies and programs are being cut, not expanded.

Transforming techno-economic-trade policy on both the offensive and defense sides of the equation cannot be done incrementally. It requires launching a new system of “national power capitalism.”

Another popular approach is to focus principally on DOD. The idea is that if DOD could procure weapons more efficiently and enable the commercial sector to play a more engaged role, much would improve. The hope is that America could then manufacture the technologies it needs for military power even if its civilian manufacturing base continues to erode. But the military’s increasing reliance on “dual use” and commercial off-the-shelf components complicates this strategy, given how weak those sectors are becoming. In addition, even if that strategy worked, it would not prevent China from gaining leverage over U.S. allies because of its increasing dominance in certain key industries.

Perhaps the most popular approach is to try to change or limit China. But one of the key lessons from the first Trump administration is that it’s not worth expending any political capital to get the CCP to change course. Its leaders simply won’t. And as time has gone on, U.S. leverage over China has continued to shrink.

The view now is that if we can’t get China to change, then maybe we can “throw sand in their gears” through export controls. And if that doesn’t slow them down enough? Just add more export controls. But as ITIF will show in a forthcoming report on how to slow China’s advance, export controls are not enough.

Finally, another approach is to decouple. The problem with that is twofold. While U.S. policy should be focused on getting all U.S. firms in national power industries out of China, that can take time. Forcing it to happen overnight would backfire. But more importantly, every yuan that U.S. firms earn from China is a yuan that does not go to Chinese firms.

The overarching guiding approach for policymakers seeking to prevent U.S. techno-economic-trade decline and eventual defeat at the hands of the PRC needs to start from scratch and be comprehensive.

It needs to start from scratch because so many of the policies and programs that need to be changed are grounded in core assumptions geared toward the post-World War II era, often from the 1960s and 1970s. These assumptions may have been valid in their day, but they will now only point us toward further decline. They include, among others, the following:

▪ Economic growth happens on autopilot, and will continue to be strong on its own. Therefore, government can impose virtually endless regulations without harming the underlying national economic engine.

▪ The United States is globally dominant in military affairs, technology, and GDP. As such, we can focus on consuming the fruits of America’s economic cornucopia, not boosting it. Moreover, trade policy and the interests of firms and workers in America can play second fiddle to overall U.S. foreign policy goals.

▪ Under no circumstances should the state play a developmental role. The prevailing view, especially since the 1970s, when classical liberalism and free-market, consumer-focused economics took hold, has been that the role of the state is on the one hand largely negative—i.e., “keeping the free-for-all of individual competition with the bounds of decorum”—while on the other hand imposing social and environmental regulations on otherwise free-market actors.

▪ The overarching goal of policy has been to enable and not interfere with allocation efficiencies in global markets with respect to the production and flow of goods, services, labor, and other factors. As such, the prevailing view has been that policies should not favor specific industries, regardless of their role in national economic power, because free markets will automatically attend to the national interest, especially when the national interest has been defined narrowly as the aggregate of short-term individual interests.

These and related core assumptions, many of which seemed appropriate for the times in which they took hold, meant that regulation became too heavy and onerous, especially toward national power industries. Too much techno-economic and trade policy was grounded in the principle of competitive neutrality among industries. And the almost religious mission to spread free trade and democracy meant that U.S. trade policy was largely blind to harms that foreign countries might inflict on U.S. national power industries.

Policymakers must start over with a fresh slate because incremental tinkering that merely improves current policy will not be enough, given the scope of the challenge.

The days when policymakers could afford to operate that way are gone. Denying that the world has changed will not bring back the halcyon days of the past. But sticking with the same doctrines, policy frameworks, and programmatic approaches—or even adjusting them through incremental reform—will not address America’s key challenge of maintaining global power, including in national power industries.

Policymakers must start over with a fresh slate because incremental tinkering that merely improves current policy will not be enough, given the scope of the challenge.

Comprehensive transformation must address all major areas of policy that affect the competitiveness of national economic power industries, including securities and investment regulation, tax, technology, trade, talent, antitrust, social regulation, and more. The relative weakness of U.S. power industries today is not due to one deficiency in the U.S. system; it is the result of a massive interplay of subsystems that are each either underperforming or contributing to weakness.

In his classic book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Thomas Kuhn posited that science proceeds not in a regular path, but rather through periodic revolutions in which new paradigms are proposed and accepted; and then for a period afterward, most “normal science” works to support and fill in the gaps in the paradigm shift.[3] This framework has applications for U.S. policy. While it’s beyond the scope of this report to lay out these demarcation points, several are identifiable.

After the War of 1812, federal policy shifted toward stronger nationalism, economic self-sufficiency, and a robust national defense. That led to the so-called “American System” of tariffs, a national bank, and internal improvements, along with a larger military and increased continental focus.

The Civil War brought another major shift, enabled in part because of the withdrawal of Southern agrarian interests from the Congress. This phase included building the transcontinental railroad, establishing land grant universities, the Homestead Act, various banking acts, and the use of tariffs as tools of national industrialization.

The New Deal and the Post-War period ushered in a much larger federal government, including banking and securities regulation, major infrastructure projects, and vast expansion of federal support for science and research, including the National Science Foundation, NASA, and DARPA; the GI Bill; more aggressive antitrust enforcement; the creation of the Small Business Administration; and efforts to establish global free trade.

By the 1960s, the United States was so dominant that policymakers could afford to shift from national developmentalism to a regulatory state, with the creation of new agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency and a massive increase in federal bureaucracy. Innovation, competitiveness, and economic growth were taken for granted, so the government’s job was to regulate capitalism, not strengthen industry.

The late 1980s saw a more modest paradigm change, with the establishment of a host of policies and programs to deal with techno-industrial challenges from Japan and Germany. Those included the R&D tax credit, new trade rules such as adding Section 301 to the Trade Act of 1974, the establishment of civilian technology programs in what was now called the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and others. Coupled with those came the emergence of free-market economics and financial capitalism, and an even stronger commitment to free trade.

Bold change grounded in a new bipartisan policy consensus may be difficult, but it is nonetheless what is needed.

That brings us to today. Now the appetite for bold change is limited, except among those on the Right who want to return to a McKinley-era America with high tariffs, among other things, and some on the Left who want a second New Deal, but this time focused not on the working class, per se, but on marginalized demographics. That has certainly produced congressional stalemate and extreme swings in the partisan agenda from one presidential administration to the next, depending on which party occupies the White House.

Against that backdrop, bold change grounded in a new bipartisan policy consensus may be difficult, but it is nonetheless what is needed. To that end, coming reports in this series will focus on particular policy areas that policymakers must address for the United States to avoid losing to China. The series will detail current policy approaches and assess their limitations, identify where transformational change is needed, and most importantly, propose what Congress and the White House can do to bring about the change.

Acknowledgments

This report is part of a series that has been made possible in part by generous support from the Smith Richardson Foundation. (For more, see: itif.org/power-industries.) ITIF maintains full editorial independence in all its work. Any errors or omissions are the author’s alone.

About the Author

Dr. Robert D. Atkinson (@RobAtkinsonITIF) is the founder and president of ITIF. His books include Technology Fears and Scapegoats: 40 Myths About Privacy, Jobs, AI and Today’s Innovation Economy (Palgrave McMillian, 2024); Big Is Beautiful: Debunking the Myth of Small Business (MIT, 2018); Innovation Economics: The Race for Global Advantage (Yale, 2012); Supply-Side Follies: Why Conservative Economics Fails, Liberal Economics Falters, and Innovation Economics Is the Answer (Rowman Littlefield, 2007); and The Past and Future of America’s Economy: Long Waves of Innovation That Power Cycles of Growth (Edward Elgar, 2005). He holds a Ph.D. in city and regional planning from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

About ITIF

The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) is an independent 501(c)(3) nonprofit, nonpartisan research and educational institute that has been recognized repeatedly as the world’s leading think tank for science and technology policy. Its mission is to formulate, evaluate, and promote policy solutions that accelerate innovation and boost productivity to spur growth, opportunity, and progress. For more information, visit itif.org/about.

[3]. Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962).