A growing body of research shows that HIV is not solely a biological disease but is profoundly shaped by social, economic, and structural factors in East and Southern Africa.

Factors such as poverty, unemployment, low education levels, and gender inequality significantly increase people’s vulnerability to infection, while inadequate access to health services, including testing, prevention, and treatment, worsens the epidemic.

Public health researchers have long recognised inequality as a powerful driver of HIV vulnerability, particularly in Kenya, where local studies show that disparities in income, education, and access to care significantly shape HIV outcomes across counties and communities.

A detailed analysis of antiretroviral treatment coverage from across the country found that poverty was the most significant determinant of treatment access, even after accounting for health system capacity and other factors.

Data from the National AIDS & STI Control Programme (NASCOP) show that women and young people in Kenya remain disproportionately affected by HIV. In 2024, women accounted for nearly 60 per cent of all people living with HIV in Kenya, and they also experienced higher rates of HIV-related deaths compared with men.

Young women aged 15–24 continue to be at especially high risk, in part because of gender inequality, limited access to sexual and reproductive health services, and socio-cultural barriers that hinder treatment and prevention efforts. Geographic disparities compound this inequality.

“Kenya’s HIV response continues to register significant progress, reflecting the strength of our partnerships and the resilience of our health systems. In 2024, an estimated 1,326,336 people were living with HIV. Of these, 97 per cent knew their HIV status, 87 per cent were receiving treatment, and 83 per cent had achieved viral suppression,” said Dr Andrew Mulwa.

A 2024 study conducted in Kibra Sub-County, Nairobi, published in the African Journal of Empirical Research, examined how household socioeconomic status shapes access to HIV care. Researchers surveyed 365 households and found that income, education, and access to health information were strongly associated with treatment uptake.

“Households with higher income were over seven times more likely to pursue HIV treatment than poorer households, those with better literacy levels were more than three times as likely to seek care, and access to HIV-related health information increased the likelihood of treatment uptake by more than six times,” the research stated.

Further, in many parts of Eastern and Southern Africa, households with limited income, low educational attainment, and poor access to reliable health information are less able to protect themselves from infection and to manage the disease if they become infected.

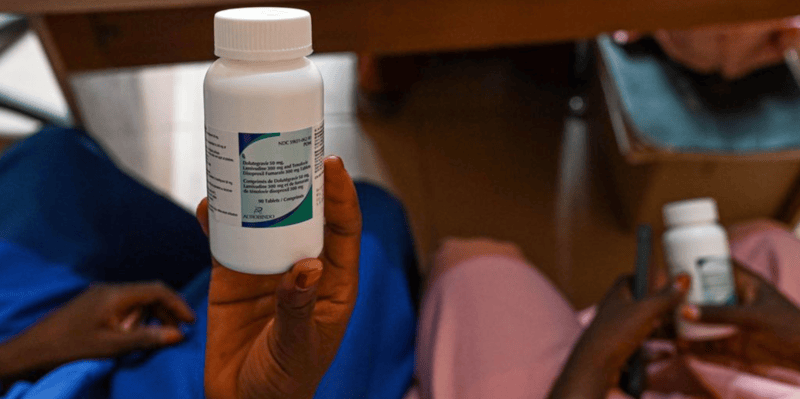

Without equitable access to regular testing, prevention tools like condoms or pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and consistent antiretroviral therapy (ART), people may not get diagnosed early or may struggle to remain in care.

This challenge is compounded when healthcare access is patchy or expensive, forcing many to delay or forego essential services—not because they lack knowledge about HIV, but because practical barriers such as cost, distance, and stigma stand in the way.

As a result, the disease continues to spread, and outcomes for people living with HIV remain uneven.

These barriers are felt most acutely at the household level, where families unable to afford transportation to clinics, interpret health messaging, or access reliable information about testing and treatment are less likely to seek care early, increasing the risk of onward transmission and worsening health outcomes.