I can still feel the bite of that first Canadian wind on my hands, sharp and cold, as my mother’s determined grip pulled me up an endless staircase to my first day of school in Toronto. Only later did I realize she was probably just as afraid as I was.

Before I could blink, we stood outside a menacing door. I hoped it might never open, but it did. My first day of Grade 4 began.

You may unsubscribe from any of our newsletters at any time.

Just as I feared, school in a new country was isolating: a swirl of words I didn’t understand, games I had never played and faces I didn’t recognize. On Sundays, however, everything shifted. In the pews, the presider offered a familiar liturgy in the languages my ears recognized. Like in most Eritrean churches, the service was primarily in Tigrinya, the most widely spoken of Eritrea’s seven indigenous languages. But the portion that always captured my attention was delivered in Ge’ez — a ”dead” language that no Eritrean communicates in. If I closed my eyes, I was back home, where I didn’t feel so alien.

Dating back to the fourth century, Ge’ez is one of the world’s oldest classical languages. Rich and intricate, it contains nuances and expressions that still lack direct translations in Tigrinya. Unlike surviving languages, which evolve with each generation, dead ones remain frozen in time. In the case of Ge’ez, which faded from everyday use sometime between the 10th and 12th centuries as Tigrinya and Tigre became more popular in what is now Eritrea, it means that no child is inheriting it as their mother tongue.

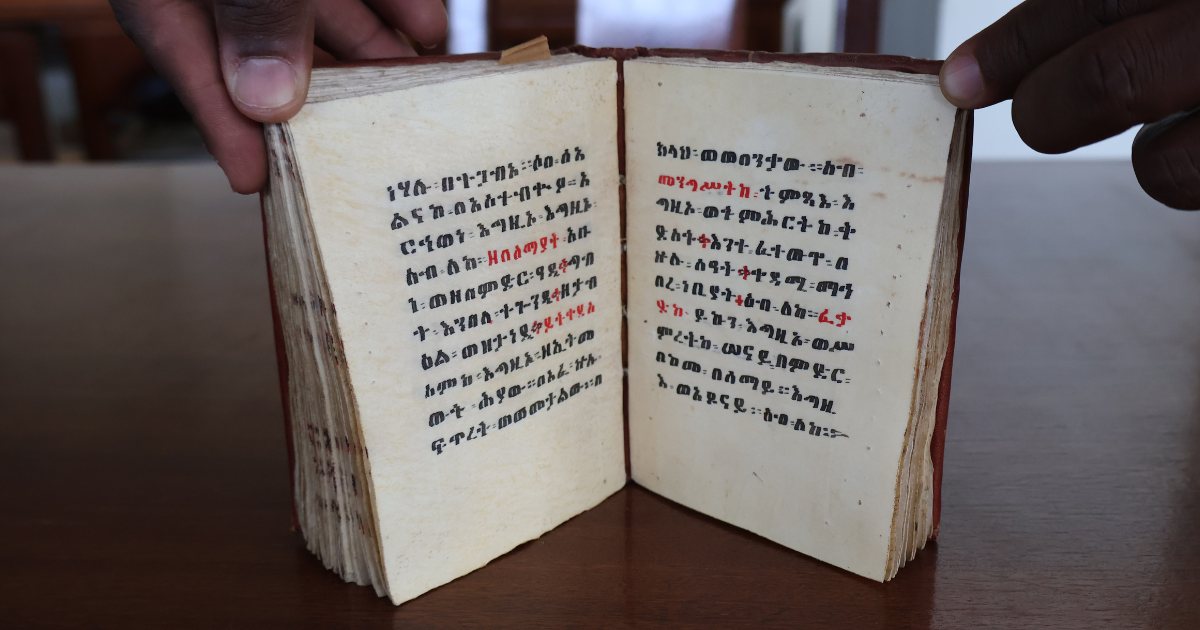

In contrast to some of the world’s other dead languages — of which Ethnologue, a language catalogue associated with the Rosetta Project, estimates there are more than 600 — Ge’ez remains an integral part of the culture that created it. It survives in hymns, in ancient manuscripts and in the quiet devotion of generations of clergy who have kept it sacred. Within church walls, Ge’ez never stopped breathing.

For most of my life, hearing it on Sundays was enough. But after 17 years in Canada, I wanted to understand why those words reached me when few other things could — and what they were trying to say. So, in May 2024, I went back home to learn the story of Ge’ez.

When I touched down to Eritrea — the most northern part of the horn of Africa, bordering Djibouti and Ethiopia — I’m quickly reminded that my mother’s land is a complicated place. The water comes and goes, electricity disappears during the middle of a conversation and potential war looms a border away. I can’t shake the feeling that I’ve been gone too long. I forgot how the sun reflects off the sand near Massawa’s deep blue sea or how the smell of spices from the city markets latches on to clothing like no perfume ever could. Inside busy cafés, the murmurs of a familiar language serve as a grand symphony by my side.

Most of my days begin at the Patriarchate of the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahdo Church, one of the country’s main centres of the faith, located in the Tiravolo neighbourhood of Asmara. Every morning at 8 a.m. sharp, I hear the sound of Aba Keshi Mengstab arriving on his motorcycle scooter.’

The Patriarchate of the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahdo Church headquarters in Asmara, Eritrea.

The Patriarchate of the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahdo Church headquarters in Asmara, Eritrea.

Mengstab told me he was raised in this church and eventually worked his way up to keshi, or priest. Before meeting him, I worried he might be a hard-nosed traditionalist, critical of my rough Tigrinya or ready to chase me out of the room for my piercings. Instead, I find an infectious eccentricity. Whether I am quietly rehearsing the right honorifics before addressing him or hurriedly flipping through my notes as he speaks, he accepts it all with a joyous spirit, eager to share everything that Ge’ez means to him.

“Our fathers and grandfathers were careful, they stored everything with care because they knew the power of what was held in their hands,” says Mengstab. “When young people take the work of Ge’ez preservation seriously and come to us for answers to their questions, I think to myself, ‘We are still here…our history lives.’”

The Eritrean Orthodox Tewahdo Church, one of the greatest guardians of the Ge’ez language, has recently taken a modern approach to preservation, digitizing ancient manuscripts to safeguard Eritrean faith and history for future generations.

Although it gradually disappeared from everyday speech, Ge’ez remained the primary written language in Ethiopia and Eritrea until the 19th century, with a few exceptions like Arabic. Its refusal to disappear serves as a sort of allegory for Eritrea itself. Colonized at various points — by the Ottomans in the 16th century, the Egyptians in the 19th century, the Italians from 1889 to 1941, the British from 1941 to 1952 and the Ethiopians from 1952 to 1991 — Eritrea has spent much of its history fighting for its existence.

Particularly brutal chapters of that history were written in the wars between Ethiopia and Eritrea — conflicts that started in 1961 and continue to this day. Though these two nations have long been divided, some of the words they speak come from the same place: Ge’ez.

Tesfay Tewoldey, an instructor and expert of Ethio -Ertirean Semitic languages at the University of Florence in Italy, explains that Eritrea and Ethiopia are home to several Semitic languages, including Amharic, Tigrinya and Tigre. “Of these languages that exist, it is popularly believed that the mother is Ge’ez,” he says. “In many ways, it represents Ethiopia and Eritrea’s resistance. When colonial powers wanted us to speak their languages, we refused — we had our own,” says Abba Ghirmai Abraha (no relation), head Jesuit teacher at the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary, known locally as “the Cathedral” — the heart of the Catholic faith in Eritrea.

Abba Abraha (left) discusses the history of Ge’ez with Nathan Abraha (right) at his office on the upper levels of the Cathedral in Asmara.

Abba Abraha (left) discusses the history of Ge’ez with Nathan Abraha (right) at his office on the upper levels of the Cathedral in Asmara.

Beyond the Orthodox Church, Ge’ez has maintained an important role in the region’s Catholic and Jewish faiths. Its survival is something Abraha — who has studied classical languages like Arabic and Hebrew and teaches Bible and Ge’ez language studies at the Cathedral to young seminarians — describes as vital to the very identity of Eritrean Catholicism. He notes Ge’ez is still shaping worship through its use in teachings and during mass.

“During the Italian colonial rule, the church was instructed to use Latin,” says Abraha. “Our ancestors resisted, teaching us that we have the right to speak what we want.”

When Portuguese Catholic missionaries came to Eritrea in the 1500s, they were surprised to find a culture with its own deeply rooted language and religion. After being largely rejected by the local population, they realized that to gain any foothold, they would have to assimilate. Later, when Swedish missionaries came to Eritrea in the 1800s, they dressed like local keshis and began teaching lessons in Ge’ez. Many missions and schools were later taken over by Italian missionaries, opening the door to the acceptance of Catholicism in Eritrea.

Monasteries — particularly those in the south- ern region of the country — have been a central part of the movement to preserve the Ge’ez language and its precious manuscripts. During my travels, I visit a centuries-old monastery called Debre Yesus in the village of Embaderho, just a 30-minute drive outside the capital. My travel companion is Yosief Asmelash, a Ge’ez academic from the Research and Documentation Centre in Asmara.

In Eritrea, it’s customary to “tsalem” before entering a holy place — a gesture of respect where you press your forehead to the entrance and lightly touch it against the wall three times. When we arrive at Debre Yesus, I walk up the steep hill and place my head against the warm stones at the entrance, pausing to think about how many others had made this climb before me. We are led inside by a monk in his 80s, the monastery’s main caretaker, and his younger pupil, who will one day take his place.

Debre Yesus holds 119 manuscripts within its walls. Over its long history, it has undergone remodelling and rebuilding. After a few minutes of shuffling through the storage room, the older monk, growing impatient, calls out to his mentee, “Hey kid, the manuscripts will age another thousand years at this pace.” The younger man eventually appears with Haimanot Abo, translating to “Father of Religion.” Its thick pages contain a peace treaty dating back to the 19th century. Some of the other manuscripts, all of which are stored in large metal containers, show signs of damage from rain and fires.

More on Broadview:

Keshi Mengstab tells me that each page of a manuscript came at a great cost. The process demanded not only precision in writing every letter, but also patience in the preparation. Traditionally, an entire village would support the creation of a holy manuscript for months, while an assistant would make sure the ink dried properly. “Even if one fly landed on the page, messing up the ink, the whole page would be rendered wasted and thrown out,” he explains.

At Debre Yesus, the monks handle each manuscript with the same care, using a string to turn each page and carefully returning them to their resting places after showcasing them. But over the years, the number of people with the expertise to take on this work has declined.

Mengstab says that if no one were to care for the ancient manuscripts, they would be lost forever. “The wind wouldn’t get in, the pages wouldn’t be flipped. There are large amounts of humidity; water would eventually get in if the place is not properly sealed.”

When asked about the importance of preserving Ge’ez for future generations, he considers what it would mean if the language were to disappear completely. “These books and manuscripts — we have to protect them so that they can protect us. If we uphold this knowledge passed down to us, we haven’t failed the teachings of those who came before us,” he says.

While the church’s efforts have kept Ge’ez alive, Mengstab believes it must remain a symbol of unity for the entire nation. “This language is not only a property of our church but of the people,” he says. “This nation’s fruits are for everyone equally. Christian or Muslim, it doesn’t matter: the water that flows in this country is for everyone to drink.”

Since returning from Eritrea, I’ve realized that, even though I may never understand every word and nuance of Ge’ez, it has been quietly teaching, grounding and connecting me to a homeland I always carry with me. A language may be dead if no mother passes it on to her child, but its spirit can still live on in those who listen. And no matter where I go in the world, as long as there’s room for one more in the pew of an Eritrean church, the language of my land will always live within me.

***

Nathan Abraha is a journalist in Toronto who covers culture, arts and politics. His latest project, Beles Magazine, is a digital publication focused on connecting the Eritrean diaspora to its cultural roots.