In humans, risk-taking is usually associated with adolescence. Broken bones, dangerous stunts, and impulsive decisions become more common in the early teen years.

Many adults assume younger children behave more carefully. Research on chimpanzees challenges that idea and offers a new way to understand how risk develops across the lifespan.

Scientists studied wild chimpanzees to explore physical risk-taking in ways that are not possible in human research due to ethical limits.

The findings reveal that the youngest chimpanzees take the greatest physical risks. Adult supervision, not biology alone, appears to shape when and how risky behavior shows up.

Chimpanzee infants take big risks

Chimpanzees spend much of their lives high in trees. Daily movement involves climbing, jumping, and dropping between branches. Falls from trees can cause serious injuries and even death, so movement choices matter for survival.

The researchers focused on two movements that involve complete loss of support. One movement involves intentional dropping from a branch.

Another involves leaping across gaps without holding on. Both actions create a short period of free flight and raise fall risk.

Age predicts risky behavior

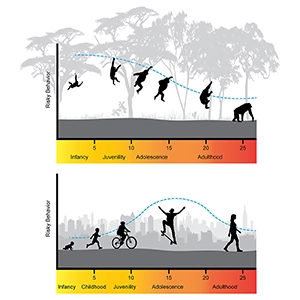

The analysis showed that age predicted risk engagement better than sex or height above ground. Infant chimpanzees showed the highest rates of risky movement.

Juveniles showed less risk, adolescents showed even less, and adult chimpanzees showed the lowest risk.

Chimpanzee infants were about three times more likely than adults to perform risky movements. Juveniles showed about two and a half times higher risk, while adolescents showed just over two times higher risk.

Sex did not matter. Male and female chimpanzees showed similar risk patterns.

Height above ground also did not reduce risk engagement, suggesting that decision-making does not depend only on distance from the forest floor.

Supervision changes risk behavior

Human children show a different pattern. Risky behavior often rises during adolescence and appears more often among boys.

Research suggests that opportunity, not a special teenage risk instinct, drives much of that pattern.

Human infants and young children rarely move without oversight. Parents, caregivers, teachers, and older children monitor movement and step in when danger appears.

This constant supervision limits exposure to risky physical actions during early childhood.

Mothers limit risk control

Chimpanzee mothers face physical limits. A mother can restrain an infant only while clinging continues or while proximity remains close enough for arm reach.

Once independent movement begins, supervision becomes difficult. Dense forest foliage further reduces visual monitoring.

Study senior author Laura MacLatchy is a professor of anthropology at the University of Michigan.

“One implication of this work is that human behavior might be having a really big impact in terms of mitigating the consequences of risky physical behavior in humans,” said Professor MacLatchy.

The research suggests that human children might show early peaks in risky play if supervision relaxed sooner.

Adolescence is generally considered the life stage with peak risk-taking among chimpanzees and also humans, though this may be specific to the type of risk. Credit: iScience. Click image to enlarge.Physical risk differs in chimpanzees

Adolescence is generally considered the life stage with peak risk-taking among chimpanzees and also humans, though this may be specific to the type of risk. Credit: iScience. Click image to enlarge.Physical risk differs in chimpanzees

Risk-taking comes in different forms. Economic risk involves uncertain rewards, such as gambling or decision games. Physical risk involves possible injury or death, and patterns differ across risk types.

Studies of economic risk show a gradual decline from childhood to adulthood in both humans and chimpanzees.

Physical risk follows a different path. In chimpanzees, physical risk peaks early and declines steadily. In humans, physical risk peaks later.

This contrast supports an important idea. Supervision shapes physical risk more strongly than any internal desire for danger. When caregivers restrict access, risk appears delayed. When restrictions fade, risk rises.

Chimpanzee risk supports learning

Risky play may serve an important role during early development. Young bones bend more easily and absorb force better than adult bones. Smaller body mass also reduces injury severity after falls.

Early risk exposure may build strength, balance, and confidence. Practice during early life may support adult skill in climbing and movement. Without early experience, adult performance may suffer.

“Competency as an adult really depends on practice when you’re little,” MacLatchy said. “Play as practice might be part of what’s going on with these kids. Then again, there may be no stopping them.”

Risky behavior in humans

Human societies across the world show strong supervision during childhood. Even in communities that appear to allow freedom, adults or older children usually remain nearby. Such care appears unique among great apes.

The findings suggest that human physical risk might rise earlier without constant monitoring. Adolescent risk may reflect increased freedom rather than a sudden change in brain wiring.

Lauren Sarringhaus is an assistant professor of biology at James Madison University and co-senior author of the study.

“One of the main findings is that all chimpanzee kids are risky, and that infant and juvenile chimpanzees are even more risky than adolescents,” said Sarringhaus. “That’s noteworthy because that is not what you see in humans.”

Chimpanzee research offers a powerful reminder that behavior grows from biology, environment, and care combined. Understanding that mix helps explain why risk looks different across species and across ages.

The study is published in the journal iScience.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–