For decades, the Tanzania-Zambia Railway, known as Tazara, symbolised both engineering ambition and African independence. But today, the once-bustling line that carried over a million tonnes of copper and freight annually has fallen into near-obsolescence, with trains crawling through cratered tracks and passenger service reduced to a fraction of its former scale. For engineers like Hezekiah Musonda, who has spent his entire career on the line, the decline has been painful.

Opened in 1976, the 1,860km railway was a joint vision of Zambian president Kenneth Kaunda and Tanzanian president Julius Nyerere, designed to bypass white-minority-ruled Rhodesia and apartheid-era South Africa. Built by China under Mao Zedong, with interest-free loans and thousands of Chinese and local workers, Tazara was a Cold War-era marvel of infrastructure and independence. Yet decades later, maintenance budgets dried up, equipment became obsolete, and freight volumes plummeted.

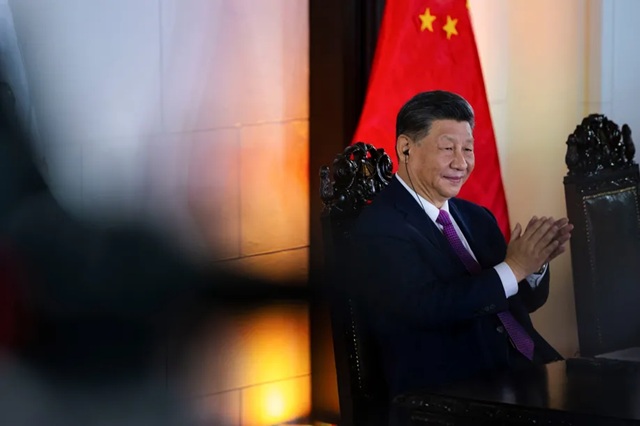

Now, Times UK reports, Tazara is poised for a dramatic comeback as China and the West vie for influence in Africa. Under President Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation is investing $1.4 billion to revamp the line, training thousands of local engineers, officials, and even journalists in the “Chinese development model.” The goal is to lift freight volumes to 2.4 million tonnes a year, a dramatic increase from the 100,000 tonnes currently transported.

But China’s investment is not without competition. The United States and the EU have launched a rival project to modernise the Benguela railway from Zambia to Angola’s Atlantic coast, backed by a $553 million loan from the US International Development Finance Corporation. According to Times UK, Washington hopes the project will promote regional trade, economic growth, and long-term US-Africa cooperation. For Zambia and the region, the rivalry has practical benefits, offering renewed opportunities for infrastructure and jobs.

Locals like Lydia Kabosha, a 68-year-old passenger, and Mukololo Chanda, the Kapiri Mposhi station master, welcome the revival. “My days are too quiet and slow,” Chanda said. “I want the Tazara running how it was.” Meanwhile, Musonda, who studied in China for over two years, believes that cooperation with both East and West is crucial. “In order for our country to do well, both will be needed,” he said.

The Tazara revival is thus more than a transport project—it is a geopolitical symbol, a test of development strategies, and a chance to restore a historic lifeline across central Africa. Times UK notes that while past ambitions were hindered by funding, politics, and neglect, the renewed attention from global powers may finally deliver on the railway’s long-dormant promise.