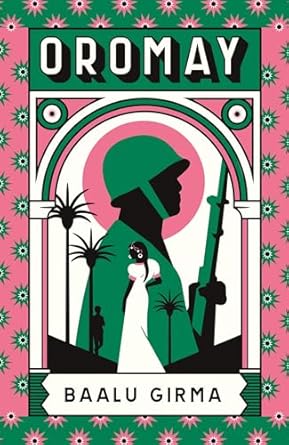

It is impossible to give an objective review to a book that led to the author’s death. It is simply impossible to weigh up the bravery it took for Baalu Girma not only to write but to publish Oromay with the fact that the world has changed significantly since 1983, when it was published in Ethiopia. Mr Girma was disappeared a year later thanks to the uproar around Oromay and remains missing, almost certainly murdered by the Ethiopian regime denounced in the book as a result of its existence. But we can only examine works of art from where we stand in the time in which we encounter them, and this, the first English translation of a book that has been beloved in its home nation since its publication, has arrived in a very different world.

It is impossible to give an objective review to a book that led to the author’s death. It is simply impossible to weigh up the bravery it took for Baalu Girma not only to write but to publish Oromay with the fact that the world has changed significantly since 1983, when it was published in Ethiopia. Mr Girma was disappeared a year later thanks to the uproar around Oromay and remains missing, almost certainly murdered by the Ethiopian regime denounced in the book as a result of its existence. But we can only examine works of art from where we stand in the time in which we encounter them, and this, the first English translation of a book that has been beloved in its home nation since its publication, has arrived in a very different world.

The narrator, Tsegaye, is the head of the Ministry of Information for the Ethiopian government, which is currently focusing on crushing the Eritrean rebellion after a decade of war. Tsegaye is a key member of the preparations for what is being called the Red Star Campaign, present at many high-level and important meetings, and able to recount in minute detail the shifting political winds among the men jockeying for position as the preparations for all-out war come together. Women, namely Tsegaye’s finance Roman, who is left behind in Addis Ababa, and Fiammetta, the woman in Asmara with whom Tsegaye develops a rocky relationship while he’s there for the campaign, are players of a different (and more stereotyped) kind.

The subplots with the women are as cliched as saying Tsegaye is torn between two lovers, breaking all the rules. Yet through Fiammetta’s knowledge of the city Tsegaye hears whispers of the rebellion that’s fermenting underneath the welcome the people are presenting the leadership. Tsegaye should know better than most not to trust what he sees, as he is the person in charge of the footage which no one but the reader can identify as political propaganda. But he is a true believer, and there are wars being fought on many fronts here.

It’s only in the last 15 or so years that the concept of “behind the scenes” has become as important as the scene itself. The modern ubiquity of cameraphones and social media means that we are used to both the image and its mirror, as well as the idea that both of these things have been faked. Previously in the west the anti-establishment fervor of the hippies in the 1960s made mocking those in power something of a sport, albeit one rarely practiced by those in power themselves. But in a dictatorship – for that is what the leadership of Ethiopia, the Derg, was from 1974 to 1991 – these concepts were unknown and therefore ground-breaking. Mr Girma was himself a member of the Derg, rising to the head of the Ministry of Information while maintaining a parallel career as a novelist. Therefore Oromay was not only the first time someone had showed what it was like behind their scenes, it was also an enormous act of defiance against them. In that sense it is absolutely no wonder that he was killed for it; the wonder is of course what gave him the courage to make this choice at all. However the book itself, in an exceptionally strong passage near the end which cannot be discussed without spoilers, makes it fairly obvious what led to the change of heart. It’s therefore only admirable that Oromay was written and published at all.

Now. For modern audiences, well used to the flaws of the people behind the curtain, the book takes a very long time to get to the point. Tedious bureaucratic meetings where men work very hard to look as if they are working hard while simultaneously deflecting responsibility for anything are reproduced in full. But within these passages there are flashes of diamond-bright insight that make sticking with it amply rewarded.

“Three reasons,” he says. “There are three reasons why this is dangerous. First, incompetent leaders will band together, united by their shared knowledge that they’re unqualified for their posts: ‘I know you, you know me, we cannot advance by merit, so instead let’s scratch each other’s backs.’ But running a country is no game, and incompetence can bring it all to a halt.

“Second, this creates a new class of opportunists, greedy reactionaries. Milovan Djilas predicted this in Yugoslavia. This new class will grant themselves special privileges because of their administrative monopoly.

“Third, power always corrupts. We can no longer feel superior to others based on personal wealth, based on our bourgeois lifestyles. The Revolution eliminated those things, but it hasn’t eliminated the desire for them. So what do people do to satisfy their desire for a comfortable life? They do whatever it takes to get the quick promotion, exaggerate their experience, pretend they have the skills. Being rational and honest won’t get you that powerful position. Once they get power, they can abuse it to obtain personal luxuries. The black market thrives that way. Our unfortunate history of corrupt officials is returning, despite the Revolution.”

And as 2025 begins to unspool at a horrifying pace, with political events around the world catching up to what the people in Ethiopia already knew in the mid-80s, Oromay might just be landing at the right time for the rest of us to learn some important lessons. It’s a vivid depiction of how power works to maintain its power, whether that’s through withholding sex, corporate backstabbing, terrorist plots, or the invasion of another country.

Any Cop?: Oromay is not the literary version of eating your spinach, i.e., something to consume because it’s good for you instead of being fun. It is both the image of what happened in Ethiopia in the 1980s and a mirror for the world right now.

Discover more from Bookmunch

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.