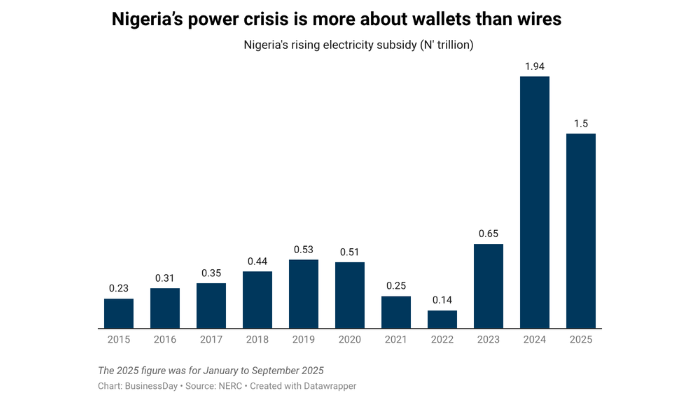

Nigeria’s power sector is consuming public cash at an accelerating pace, forcing the government to spend hundreds of billions of naira on subsidies to keep electricity flowing, even as decades of reforms and billions of dollars in investment have failed to deliver a reliable supply.

President Bola Tinubu, who took office in May 2023, promising tough economic reforms, is caught between the political risk of higher electricity tariffs and the fiscal reality of a power market that cannot pay its own bills.

While his administration scrapped petrol subsidies soon after assuming office, triggering nationwide protests, it has moved far more cautiously on electricity pricing, wary of voter backlash ahead of the 2027 elections.

Read also: More trouble for hobbled electricity market as 20 more firms dump national grid

Subsidy costs are being driven by an aging grid that loses as much as 40 percent of generated power, weak revenue collection, and tariffs that fall well below the true cost of supply.

For instance, between October 2024 and September 2025, the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC) haemorrhaged cash at an average rate of N165 billion per month to bridge the gap between what consumers pay and the actual cost of generating power.

The subsidy spending remained stubbornly high throughout the period, according to NERC data.

In the fourth quarter (Q4) of 2024, the government incurred N471.69 billion in electricity subsidies. That figure climbed to N536.4 billion in the first quarter (Q1) of 2025 before moderating slightly to N514.35 billion in the second quarter (Q2).

The third quarter brought some relief with subsidies declining to N458.75 billion, though the total still represents a massive drain on public finances.

“In the absence of cost-reflective tariffs, the government undertook to cover the resultant gap between the cost-reflective and allowed tariff in the form of tariff subsidies,” NERC stated in its latest quarterly report.

The subsidy surge comes as distribution companies, the crucial link between power generation and end consumers, continue to collect far less revenue than they bill customers, creating a gaping financial hole that the government has been forced to fill.

As of October 2025, Nigeria’s 11 distribution companies billed customers N2.4 trillion but collected only N1.9 trillion, leaving a 20 percent revenue gap that cascades through the entire electricity value chain.

Industry analysts say the subsidy regime has become politically toxic ahead of Nigeria’s 2027 general elections, constraining the government’s ability to implement painful but necessary reforms.

With memories of petrol subsidy removal protests still fresh, the federal government appears reluctant to inflict similar hardship on voters by raising electricity tariffs to cost-reflective levels, even as the fiscal burden becomes unsustainable.

“The government is caught between a rock and a hard place,” said Chidi Okonkwo, an energy analyst at Lagos-based Frontier Economics. “They know subsidies are bleeding the treasury dry, but they’re terrified of the political backlash from removing them in a pre-election year. So, the problem just keeps getting worse.”

Read also: Nigeria’s electricity subsidy hits ₦1.98tn in 12 months despite tariff hikes

Generation crisis compounds subsidy burden

The financial haemorrhaging in Nigeria’s power sector is worsened by chronic underperformance at the generation level, where installed capacity vastly exceeds actual output.

According to lastest data from NERC, the country’s grid-connected power plants have a combined installed capacity of 13,625 megawatts, yet average plant availability stands at just 38 percent.

This means that on any given day, nearly two-thirds of Nigeria’s theoretical generation capacity sits idle or unavailable.

Olorunsogo 2, with an installed capacity of 750 megawatts, delivers a mere 23 megawatts of available capacity, operating at just three percent availability. Alaoji 1, designed for 500 megawatts, contributes nothing to the grid with zero available capacity in December.

Sapele Steam 1 mirrors this dysfunction, delivering only 23 megawatts from its 720 megawatt capacity, a catastrophic three percent availability rate. Even among the top performers, significant capacity remains locked away. Egbin 1, the largest single producer, delivers 545 megawatts from its 1,320 megawatts installed capacity, while Delta 1 provides 454 megawatts against its 900 megawatt potential.

A handful of smaller plants demonstrate that full utilisation is technically possible, further underscoring the systemic failures elsewhere.

Ikeja 1 operates at 100 percent availability, delivering all 110 megawatts of its installed capacity. Zungeru 1 similarly maximises its 700 megawatt capacity at 100 percent availability. Yet these success stories only highlight the scale of underperformance across the majority of facilities. Odukpani 1 delivers just 117 megawatts from 625 megawatts installed, while Ihovbor 1 manages only 39 megawatts from its 500 megawatt capacity.

The great industrial exodus

What makes the situation particularly precarious is the accelerating flight of Nigeria’s largest electricity consumers from the national grid.

Manufacturing giants, telecommunications companies, and commercial enterprises have invested billions in captive power generation, installing diesel generators and, increasingly, solar installations to guarantee a reliable electricity supply.

Dangote Group, Nestle Nigeria, Nigerian Breweries, and dozens of other major corporations now generate most of their power needs independently. The telecommunications sector alone is estimated to spend over $2 billion annually on diesel for generators, powering the more than 30,000 base stations scattered across the country.

This industrial exodus has fundamentally altered the economics of Nigeria’s power sector. The national grid, originally designed to serve both high-paying industrial customers and subsidised residential users through cross-subsidisation, now serves a customer base dominated by lower-revenue households and small businesses.

“You’ve lost your anchor tenants,” explained Amina Bello, a former adviser to the Ministry of Power. “The customers who could pay cost-reflective tariffs and subsidise others are gone. What remains are residential customers, many of whom are struggling economically and can’t afford even current rates.”

Read also: Gombe joins other states to secure autonomy over electricity market regulation

Nigeria’s power sector has long been Africa’s most notorious infrastructure failure. Despite privatisation in 2013 that was meant to usher in efficiency and investment, the country of more than 200 million people generates less electricity than a small European nation.

Peak generation rarely exceeds 5,000 megawatts, a fraction of estimated demand of 30,000 megawatts.

Under the current multi-year tariff order, most Nigerian electricity consumers pay rates that cover only a fraction of generation, transmission and distribution costs.

NERC has approved limited tariff increases for certain customer classes, including a controversial hike for Band A customers who receive at least 20 hours of daily supply, but the vast majority of consumers remain heavily subsidised.

Experts say the gap between what Nigerians pay and what power actually costs has widened due to multiple factors. Naira devaluation has increased the local-currency cost of gas imports and equipment. Inflation has pushed up operational expenses.

Poor revenue collection by distribution companies means much of the power generated is never paid for, further distorting the economics.

The political conundrum

Other experts said the subsidy trap had become particularly acute as Nigeria approaches its 2027 general elections.

“These subsidies are essentially welfare payments disguised as infrastructure spending,” said Aisha Mohammed, an energy analyst at the Lagos-based Centre for Development Studies.

Mohammed added, “They don’t improve service, they don’t attract investment, and they certainly don’t fix the fundamental problems in the power sector. They just postpone the day of reckoning while draining resources that could fund education, healthcare or real infrastructure.”

Read also: The power question: Will settling gas debts finally stabilise Nigeria’s electricity market?

The timing of the subsidy escalation is particularly problematic for a government already facing severe fiscal constraints.

Nigeria’s budget deficit has ballooned in recent years, forcing increased borrowing at a time when debt service consumes more than 70 percent of federal revenue.

Removing petrol subsidies in mid-2023 was meant to free up resources for development spending, but much of those savings appear to be flowing into the electricity subsidy rat hole.

International lenders, including the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, have repeatedly urged Nigeria to eliminate electricity subsidies and move to cost-reflective pricing.

Dipo Oladehinde is a skilled energy analyst with experience across Nigeria’s energy sector alongside relevant know-how about Nigeria’s macro economy.

He provides a blend of market intelligence, financial analysis, industry insight, micro and macro-level analysis of a wide range of local and international issues as well as informed technical rudiments for policy-making and private directions.