The former Tigray interim president’s repositioning acts against accountability for the Tigray war.

In post-war societies, the way violence is explained is never incidental. How leaders recount the origins of conflict, assign responsibility, and characterize the victims’ experience shape both historical memory and prospects for accountability. In such contexts, a lack of clarity redistributes blame.

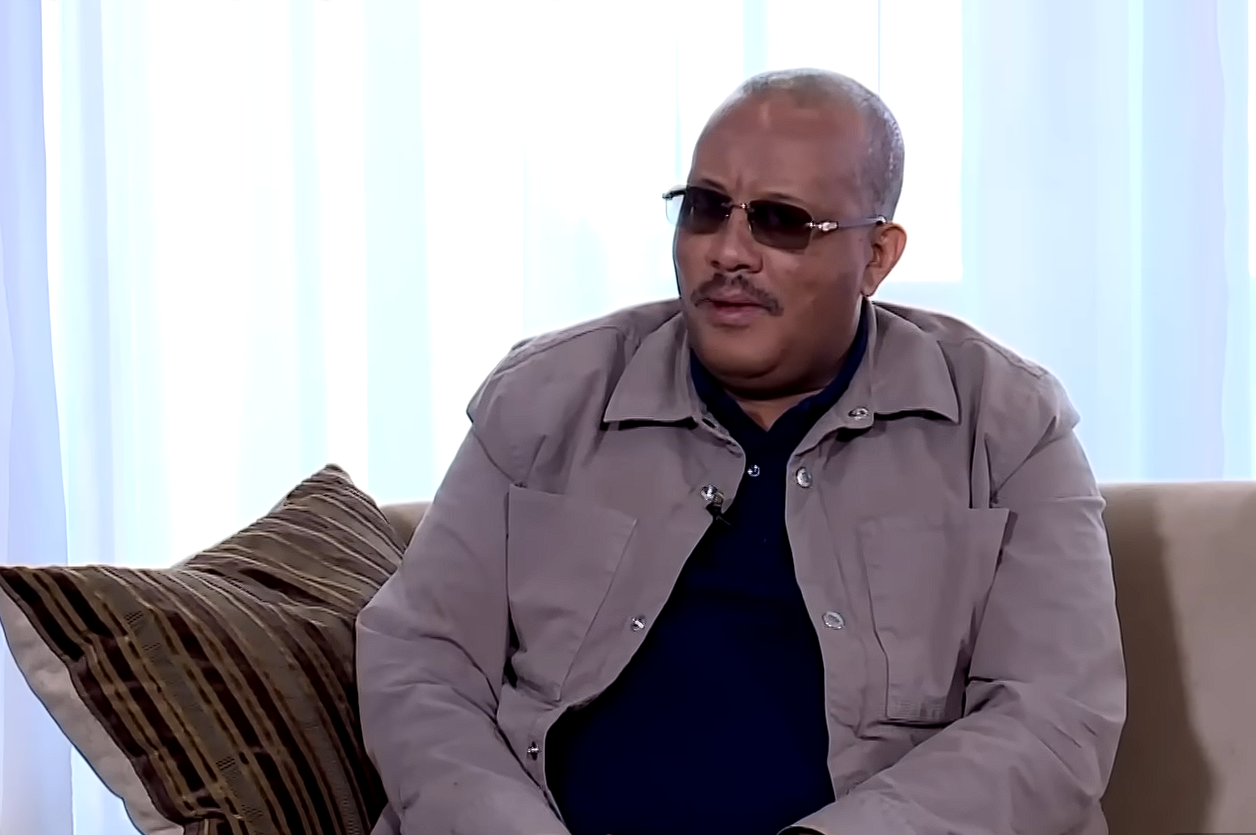

A recent interview by Getachew Reda does precisely that. Presented as reflective and self-critical, the interview reconstructs the Tigray war through a narrative that diffuses responsibility, and selectively absolves state power for a devastating war. His argument relies on abstraction and sophistry masked as reasoned analysis.

This critique is not an attempt to idealize the former Tigray leadership, nor is it an endorsement of alternative figures or factions. It is an insistence on principled analysis: that leadership failure must be distinguished from responsibility for war; that rhetoric must not be confused with causation; and that genocide cannot be narrated away through blame-shifting.

Blame Reversal

At the center of Getachew’s argument is the claim that the war resulted primarily from the belligerence and rhetorical excess of the Tigray leadership, despite repeated calls for peaceful resolution from Abiy Ahmed.

This framing reverses cause and effect. It detaches the outbreak of war from the political and institutional conditions that preceded it: the systematic undermining of constitutional federalism, the criminalization of regional authorities, the postponement of national elections, and the deliberate political and economic isolation of Tigray.

Wars of annihilation are not triggered by rhetoric. They are initiated through decisions by actors who possess and deploy sovereign military power. To treat discourse as the primary cause of war is to mistake context for causation and to obscure agency where it matters most.

This does not mean the Tigray leadership was blameless. It is reasonable to argue that the leadership misjudged the scale and brutality of the impending war, underestimated the willingness of the federal government and its allies to employ mass violence, and failed to prepare for worst-case scenarios.

More rigorous threat assessment, and diplomatic engagement might have mitigated—though not prevented—the catastrophic human cost. But strategic miscalculation is not the same as responsibility for war. Collapsing these distinctions shifts accountability away from those who planned, and executed a campaign of mass violence and onto those who failed to anticipate its full extent.

The interview’s weaknesses lie in the selective nature of the self-critique. Getachew professes a readiness to “take responsibility” for mistakes made while in leadership, often describing himself as someone who recognized errors but went along with the collective momentum.

While responsibility is acknowledged in the abstract, blame for belligerence and escalation is assigned to “the leadership”, a residual category from which he implicitly distances himself. If rhetoric is advanced as a meaningful factor in the escalation of conflict, accountability must be allocated consistently. As the principal spokesperson and a senior member of the Tigray leadership before and during the war, Getachew exercised substantial influence over public communication and external framing.

Elements of his rhetoric—particularly its confrontational and unmoderated tone—contributed to polarization, diplomatic estrangement, and reputational costs. Acknowledging error only as acquiescence to collective dynamics, while assigning decisive agency to others, preserves moral standing without assuming proportional responsibility.

Abstracting Genocide

A similar diffusion appears in the interview’s treatment of genocide. Getachew assigns roughly 76 percent of responsibility for the genocide in Tigray to Eritrean forces, attributing the remainder to a range of hostile or resentful actors.

This quantitative framing is analytically flawed. While empirical data may describe the scale of violence, genocide is not determined by proportional thresholds but by political decisions, command structures, and enabling conditions that organize the destruction of a targeted group.

Most importantly, it marginalizes the role of the Ethiopian state. Eritrean forces did not operate independently. Their entry into Ethiopia occurred through invitation, and sustained alliance with the federal government. Foregrounding Eritrea while diluting Ethiopian state agency is a further displacement of culpability.

Getachew also echoes state securitization narratives long used to justify repression. Claims of a collusive alliance involving Eritrea, Fano, and the TPLF mirror official discourse deployed to legitimize mass arrests and other forms of collective punishment.

This pattern extends to the interview’s use of literary and philosophical references. Works such as One Hundred Years of Solitude are invoked as signals of intellectual authority, untethered from engagement with causation, responsibility, or historical memory. In the context of mass atrocity, such gestures risk trivializing both literature and suffering.

The retreat from clarity continues through legal abstraction. In refusing to label what occurred in Tigray as genocide, Getachew defers to courts, presenting the determination as a legal question rather than a moral and political one.

While judicial accountability is indispensable, the reality of genocide does not await courtroom validation. It is first experienced by victims through mass killing, starvation, systematic sexual violence, and the destruction of social life long before it is formalized in legal rulings.

More troubling is the insinuation that genocide remains morally indeterminate until sanctioned by institutions that operate within political constraints. Courts do not function in vacuum; they are shaped by power relations, and geopolitical interests.

If a court were to delay, or deny a genocide determination for political reasons, would the crime itself cease to exist? Would the suffering of victims be retroactively annulled?

Such reasoning collapses moral truth into procedural outcome and replaces collective memory with institutional convenience. In post-genocide contexts, deferring recognition until judicial confirmation amounts to a withdrawal from solidarity with victims.

Moral Reckoning

The most disturbing claim in the interview is the assertion that at the height of the war and genocide, the people of Tigray sought the intervention of the Ethiopian National Defense Forces (ENDF). This contradicts documented reality.

During that period, ENDF—alongside Eritrean troops and allied militias—were enforcing siege conditions, facilitating starvation, and committing widespread atrocities against civilians. To suggest that a besieged population welcomed its own destroyers inverts moral reality and risks erasing victimhood.

Taken together, these positions reveal a consistent pattern. Responsibility is shifted outward and downward, away from sovereign power and toward rhetoric, internal discord, and abstraction. Leadership failures are elevated into causation, while state agency recedes into background context.

Reconciliation cannot rest on narrative convenience, and justice cannot survive the systematic diffusion of responsibility. For Tigray—whose people endured siege, starvation, mass killing, and systematic violence—narrative integrity is a political necessity.

How this war is explained will determine whether accountability remains possible or whether impunity is quietly normalized under the guise of reflection.

Query or correction? Email us

While this commentary contains the author’s opinions, Ethiopia Insight will correct factual errors.

Main photo: Getachew Reda, Prime Minister’s Advisor on East African Affairs, Addis Ababa, December 2025. Source: NBC Ethiopia.

Published under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence. You may not use the material for commercial purposes.