Far above northern Ethiopia’s patchwork fields, villagers in Wollo have uncovered a rich, natural black opal deposit almost 9,800 feet above sea level.

Their tunnels follow a single opal-bearing clay layer that runs along the highland mountains for many rugged miles.

“The Stayish black opal mine, active since 2013, is located in the Wollo province of northern Ethiopia,” wrote Dr. Lore Kiefert, chief gemologist.

She works at Gübelin Gem Lab (GGL), where her research focuses on gemstone origin and advanced laboratory characterization.

Her team describes a distinct opal-bearing clay layer about 2-feet thick that tracks the mountain belt for many miles.

Local villagers practice artisanal mining, which is hand-dug family-run mining work, cutting tunnels 50 to 65 feet into the hillside along the seam.

Most opal pieces pulled from the layer are small nodules barely an inch across, with rare chunks stretching close to 4-inches long.

White, crystal, and black opals

Early mining in the 1990s at Mezezo brought nodules of orange precious opal, transparent opal with bright color flashes, but not black stones.

In 2008 miners near Wegel Tena in Wollo uncovered white and crystal opal from volcanic rocks, now studied as Ethiopian material.

That white Wollo opal often behaves as hydrophane, porous opal that soaks water, enabling gem treaters to experiment with dye effects.

Before Stayish, researchers documented an Ethiopian black opal whose bodycolor came from manganese-rich minerals, underlining how rare dark material was.

Horizontal tunnels cut into the slope

Once a promising spot is found, crews swing pickaxes along the clay horizon, hauling bucket after bucket of rock out through the entrance.

Inside those tunnels, the ceiling can hang low over earth, and miners rely on timber props and experience rather than machinery for support.

Many villagers farm during the rainy season, then spend dry months underground hoping stones will bring cash for school fees or tools.

When a patch of color appears in the wall, miners switch to small chisels and water and ease the opal out carefully.

Thin clay black opal layer

Geologists see the Stayish opal in a stratum, single rock layer marking the boundary between volcanic rock and clay sediments where miners dig.

The layer lies between volcanic ash and ignimbrite, hardened rock from once fast-moving ash flows, across a wide region.

Field crews have traced this opal layer along the highlands for dozens and possibly hundreds of miles, revealing a surprisingly continuous geological target.

Within that clay, some pockets carry play of color while others hold common opal, dull opal lacking strong color flashes.

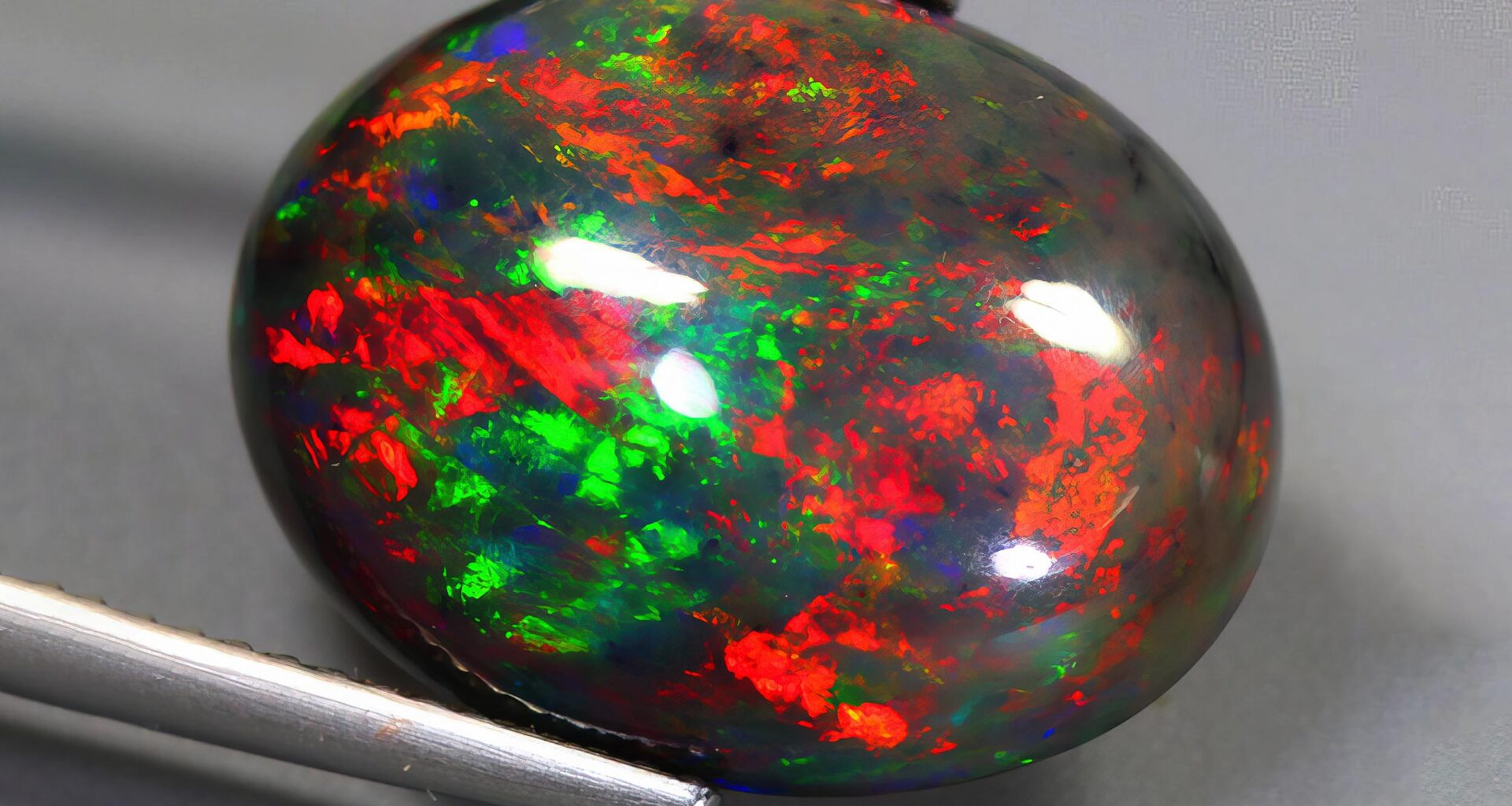

Ethiopian black opal is different

The Stayish stones show a natural dark bodycolor that resembles treated material, yet surfaces stay clean with no staining in pits or scratches.

When cut in sections, the black bodycolor runs all the way through pieces, sometimes layered with gray common opal that borders color patches.

Using X-ray fluorescence, which is a method measuring elements using X-rays, researchers measured barium from undetectable to 1,000 parts per million in these opals.

Unlike hydrophane white opals from Wegel Tena, Stayish black stones seldom absorb water and are often considered more stable in finished jewelry.

Treated opal and the risk of confusion

Treaters take advantage of Ethiopian opal, using smoke, sugar acid solutions, and dyes to turn light material into stones that resemble black opal.

Smoked stones leave black residue in pits and fractures, while sugar acid treated pieces may show a thin darkened rind over paler opal.

As demand for Ethiopian black opal has grown, a share of available stones are smoked or dyed hydrophane opal rather than dark Stayish material.

Buyers who want color ask for laboratory reports, test how a stone behaves in water, and look for disclosure about source and treatments.

Challenges of cutting black opals

Stayish rough often shows sharp fractures and uneven color patches, so cutters study each piece carefully before deciding how to orient a cabochon.

A cabochon is a type of gemstone cut where the stone is shaped and highly polished with a convex, domed top and a flat or slightly rounded base.

Aggressive grinding can trigger crazing, networks of cracks from stress, so cutters keep wheels slow, use water, and tolerate breakage rates above usual.

Once the stone reaches a ring or pendant, careful owners avoid temperature swings, dry heat, and storage near light that can strain opal.

Although Stayish opal usually resists water, its background shows wear, so owners favor soap, lukewarm water, and a cloth instead of ultrasonic cleaning.

Reshaping the black opal market

Collectors once relied on Lightning Ridge in Australia for black opal, but Stayish material offers a growing second source with its own look.

As word spreads, Stayish gemstones still sell for less than many Australian blacks, while top stones showing bright multi-colored flashes command collector prices.

Jewelers are pairing Ethiopian black opal with gold, leaning into color patches and patterning that differ from narrow flashes seen in Australian stones.

Stories about the gems highlight origin, describing Ethiopian black opal mined by hand from tunnels cut by villagers instead of from open pits.

Local opportunity, long-term care

The Stayish discovery has brought cash and visitors into Wollo villages, yet earnings remain uneven and depend on a few finds each season.

Geologists and officials working with cooperatives can help by encouraging safer tunnel designs, adding timber supports, and creating channels that reward miners.

Collectors and dealers influence conditions when they ask detailed origin questions, support transparent supply chains, and favor partners working directly with village miners.

That black opal seam beneath Wollo now links tunnels, gem labs, and jewelry counters in ways few villagers imagined when they began digging.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–