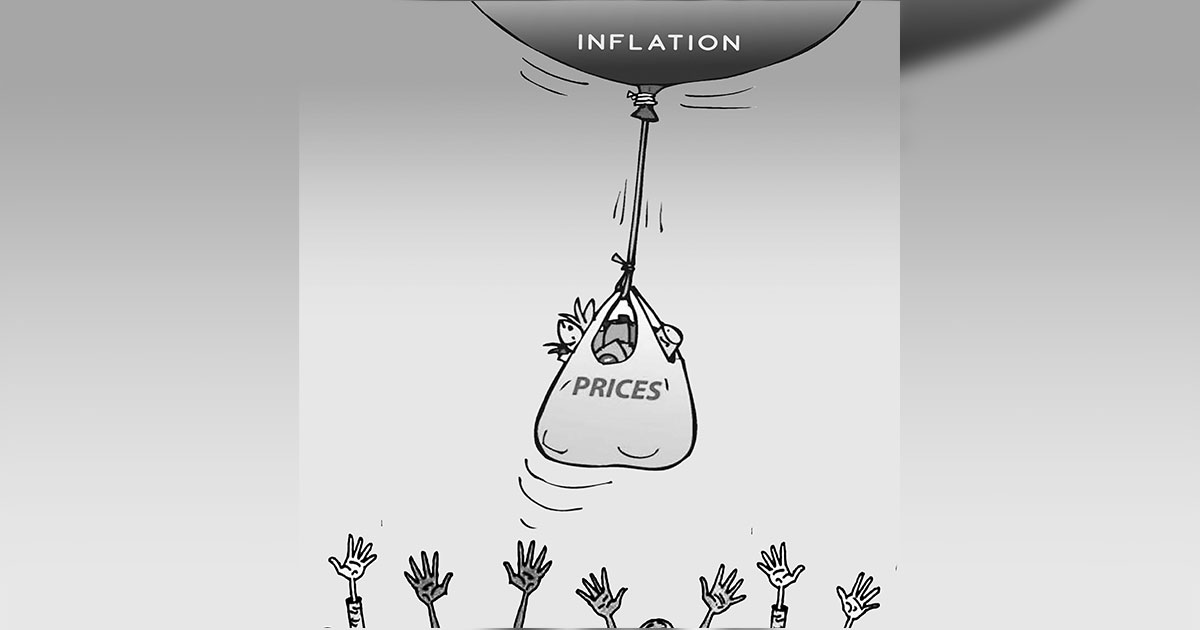

The recent announcement by the Ethiopian Statistical Service that Ethiopia’s year-on-year inflation rate dipped to 9.7 percent in December 2025 was heralded as a milestone. After years of double-digit inflation, the headline figure suggested that price pressures were finally easing. Yet beneath the surface, doubts abound. Can this single-digit rate be trusted in a country that only recently floated its currency, exposing the birr to market volatility? And more importantly, does this statistic reflect the ordeal of households struggling to afford food, rent, and basic necessities?

The credibility question arises from the disconnect between official data and everyday experience. Ethiopia’s consumer price index is heavily weighted toward food and non-alcoholic beverages, which account for more than half of the basket. While the official report noted moderation in some categories, it also acknowledged sharp increases in staples such as coffee, sugar, and meat. For families whose budgets are dominated by food, these spikes overshadow the headline easing. The floating of the birr some 18 months ago further complicates matters. Although the currency liberalization was intended to attract investment and improve competitiveness, in the short term it has fueled exchange-rate volatility, raising the cost of imports and eroding purchasing power. Against this backdrop, the official single-digit inflation rate risks appearing more like a statistical artifact than a reflection of economic reality.

Admittedly, this credibility gap is not unique to Ethiopia. Across Africa, governments face pressure to demonstrate economic progress, sometimes leading to optimistic reporting that clashes with lived experience. Ethiopia’s case is particularly sensitive though. The country has endured years of conflict, debt distress, and external shocks. For ordinary citizens, the cost of living has risen astronomically over the past decade or so. Rent in major cities like Addis Ababa has surged, transport costs have climbed with fuel price adjustments, and food insecurity remains widespread. When official statistics suggest relief but daily life feels harsher, trust in institutions erodes.

Addressing this crisis requires more than statistical recalibration. It demands a comprehensive strategy to tackle the cost of living. First, improving food is crucial. Ethiopia’s inflation is largely driven by food prices, reflecting structural weaknesses in agricultural productivity, logistics, and market access. Investments in irrigation, storage facilities, and rural roads can reduce volatility and stabilize supplies. This must be augmented by measures aimed at security strengthening social safety nets. Despite limited coverage, Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Program has provided support to vulnerable households. Expanding cash transfers, food subsidies, and targeted assistance can cushion the poorest against price shocks. It is also of the essence to handle currency management with care. Floating the birr was a bold step, but without adequate reserves and credible monetary policy, volatility will persist. As such the central bank must build credibility through a transparent management of exchange rates, curbing speculative pressures, and coordinating with fiscal authorities to avoid runaway deficits. Civil society and independent data collection should be encouraged as well. When official statistics are questioned, alternative sources of data—such as surveys by universities, NGOs, and independent think tanks—can provide checks and balances. Transparency builds trust, and trust is vital for economic stability.

Most critically, it is absolutely critical to confront supply-side constraints that drive up costs. Inflation in Ethiopia is not only a monetary phenomenon; it is a structural one. Poor infrastructure, limited storage, fragmented markets, and weak logistics chains mean that food and goods often fail to reach consumers efficiently. Farmers lose crops to post-harvest spoilage, traders face high transport costs, and urban markets suffer shortages. Tackling these bottlenecks requires investment in roads, rail, energy as well as reforms to reduce bureaucratic hurdles for producers and traders. Encouraging private-sector participation in logistics and agro-processing can go some way towards stabilizing supplies and reducing costs.

While we are not accusing here the government of falsifying inflation data, imagining the gap between official figures and lived reality helps illuminate the fragility of the social contract. It reminds us that sovereignty, law, and norms are constantly contested. For Ethiopia, the lesson is clear: credibility cannot be taken for granted. It must be defended through unity, resilience, and principled commitment to transparency. In a world where power often bends rules, the country must insist that rules matter. Only then can it safeguard its independence and dignity in the face of global turbulence.

In December 2025, Ethiopia joined the ranks of countries boasting single-digit inflation. Yet the true test lies ahead. Will this figure mark the beginning of genuine relief, or will it remain a statistical mirage? For the millions of Ethiopians struggling to make ends meet, the answer will not be found in spreadsheets but in the price of bread, the cost of rent, and the dignity of daily survival. Credibility is earned not through numbers but through action. Ethiopia must act decisively to confront its cost-of-living crisis, or risk losing the trust of its people at a time when trust is most needed.