One thousand people, all dressed in the same oversized satin suit, bowtie and hat, march through the streets of Cape Town, South Africa. They dance, parade, sing and play brass instruments in highly choreographed numbers. Over the course of a month, this klopse — “club” or “troupe” in English — will compete against dozens of other clubs in many different categories.

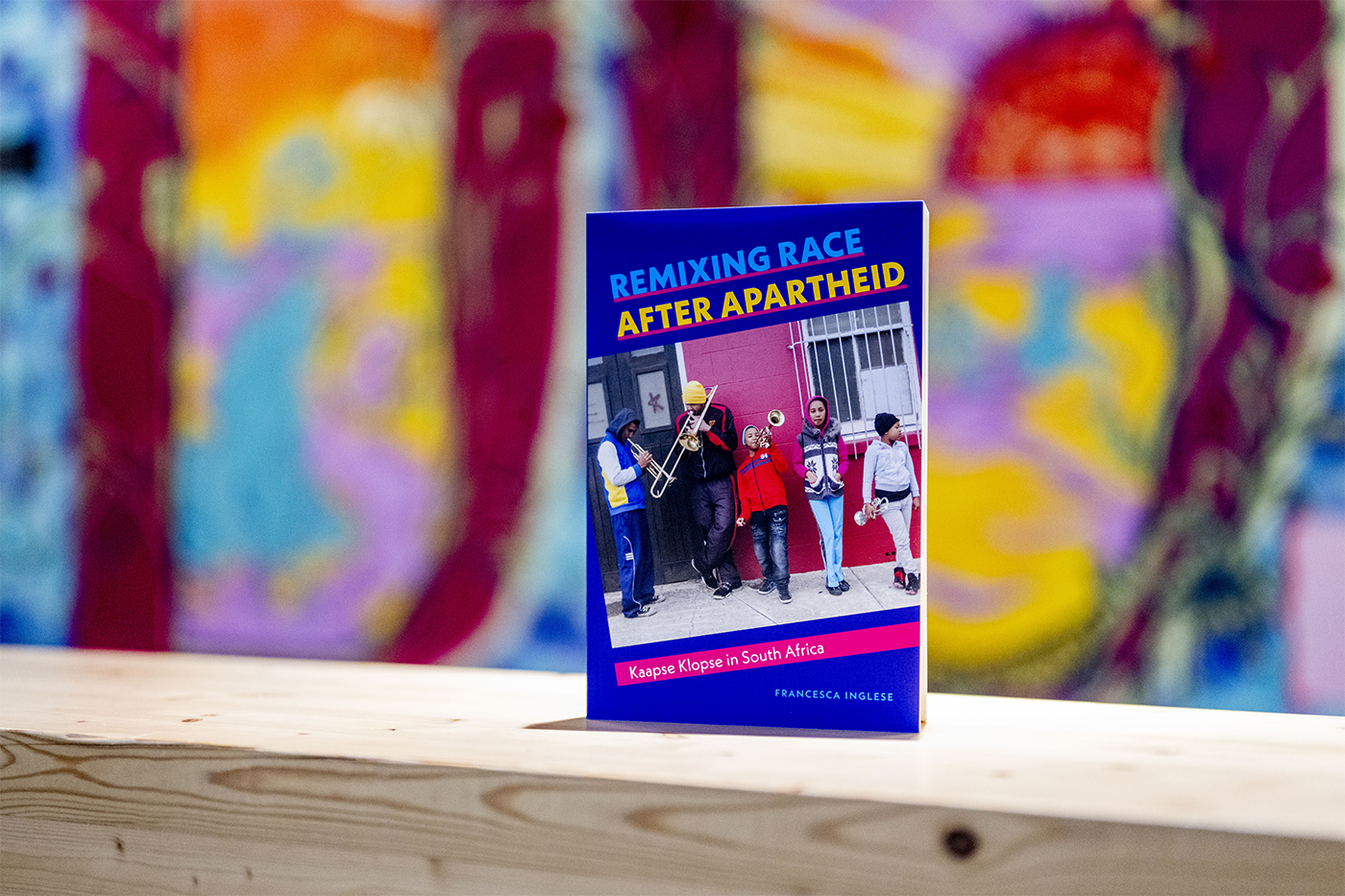

This is Kaapse Klopse, a social music and dance practice that emerged during South Africa’s colonial and apartheid periods as a collective celebration. In the post-apartheid period, it has become a celebration of historical struggle and a way for people to mingle and parade, despite having a complex relationship to issues of race, according to a new book, “Remixing Race After Apartheid: Kaapse Klopse in South Africa,” recently released by Northeastern University assistant professor of music Francesca Inglese.

Inglese went to South Africa to experience the movement herself over three years of fieldwork.

She describes Kaapse Klopse as “a practice that’s both of sound but also of the body.” For her, klopse is an important mediator of urban space and social identity in contemporary South Africa. “Sound and the body are completely intermixed in this practice,” she says.

Kaapse Klopse is also known as the Cape Town Minstrel Carnival.

A club by any other name

Kaapse Klopse means “clubs of the Cape” in Afrikaans, Inglese says, referring to Cape Town. How many clubs there are fluctuates, but when Inglese conducted her research, it hovered around 30, with participants numbering from about 100 to over 1,000 in each troupe.

They prepare throughout the year to parade and compete during January and February, summer in the southern hemisphere. They call this period carnival, though it is not the same carnival period celebrated by some Catholics prior to Lent.

02/23/24 – BOSTON, MA. – Francesca Inglese, Northeastern professor of music, poses for a portrait on Friday, Feb. 23, 2024. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

02/23/24 – BOSTON, MA. – Francesca Inglese, Northeastern professor of music, poses for a portrait on Friday, Feb. 23, 2024. Photo by Alyssa Stone/Northeastern University

Inglese’s book, “Remixing Race After Apartheid: Kaapse Klopse in South Africa,” embarks on a process of sensory ethnography, she says. Other scholars have written about Kaapse Klopse, she notes, but the practice is nevertheless still largely derided by those outside the tradition, partly because of its use of popular music and partly because of its complex relationship to race.

Inglese wanted to take a different tack, to write about the experience of practicing intensely, wearing the uniform and parading for hours at a time under a hot sun, from the inside. She wanted to ask, “What is it that’s most valuable about this practice to the people who make and produce it and who labor at it for so many months of the year?”

Complicated history

The historical site of Cape Town’s carnival, Inglese says, was a neighborhood called District Six, which was home to very diverse populations of native South Africans and immigrants to South Africa. But when the National Party installed apartheid in the late 1940s, District Six was emptied of its residents and handed over to white South Africans.

Now, klopse troupes begin their parades in District Six in honor of those who once lived there, with “a real sense of diasporic return,” Inglese says.

Inglese describes much of her time with Kaapse Klopse as “joyful labor.” Over three years of fieldwork, she embarked on a process of sensory ethnography, experiencing the carnival from the inside. Courtesy photos.

Jan. 2, the day carnival begins, was a former slave holiday in Cape Town, the one day of the year slaves weren’t required to work, Inglese says. Slavery was abolished in South Africa in 1834, according to South African History Online.

Inglese says that klopse practice is also primarily associated with “Coloured” South Africans — a legal term invented during the British colonial period and solidified during apartheid to describe citizens who were in neither the “White” nor “Black” categories as determined by the National Party. This status carried its own legal restrictions.

Many South Africans have embraced the term, Inglese says, although it’s still a point of debate and contention. Nevertheless, because of the diversity found in Cape Town’s historic District Six, klopse has long been considered a practice of people who would have been categorized as “Coloured,” although today anyone is welcome to join.

Inglese says that the majority of the participants she interviewed were aware of how “Coloured” had been invented, “as all racial categories are, including white and Black.” But nevertheless, that constructed identity has come to be filled with cultural practices, like Kaapse Klopse, she says.

To add another complicating layer to the issue of klopse and race is that the practice’s costumes, sounds and embodied gestures, Inglese says, are derived from American minstrel acts that traveled through South Africa in the 19th century, often wearing blackface, troubling klopse further in present-day understanding.

Acknowledging that “in the United States, blackface minstrelsy was a practice of white supremacy,” Inglese wanted to ask, “What does it mean for non-white South Africans to be performing elements” of minstrelsy?

Participatory research

At each juncture, Inglese was careful to center the experience of the participants, whose own lived experience drove her research.

As she reviewed her notes for the book, Inglese was struck by how much mention she made of exhaustion, she says with a laugh. Participation was an important part of her research. While acknowledging that her experience of the parades would never be the same as someone who had lived it for decades, “there is something through participation as an ethnographer that grants you a certain kind of intersubjective experience.”

In much of the practice of Kaapse Klopse that she experienced, Inglese says that there was also “joyful labor.”

Northeastern Global News, in your inbox.

Sign up for NGN’s daily newsletter for news, discovery and analysis from around the world.

Noah Lloyd is the assistant editor for research at Northeastern Global News and NGN Research. Email him at n.lloyd@northeastern.edu. Follow him on X/Twitter at @noahghola.