“Hakuna matata”, which translates to “no worries” or “no problems”, is rarely heard in everyday conversation across East Africa.

In Kenya and Tanzania, Swahili speakers are more likely to say “hamna tabu” or simply “no worries”.

The phrase itself is often reserved for tourists, cheerfully deployed at airports, hotels and safari lodges as a form of linguistic hospitality.

Yet the expression has travelled further than most of its native speakers ever will.

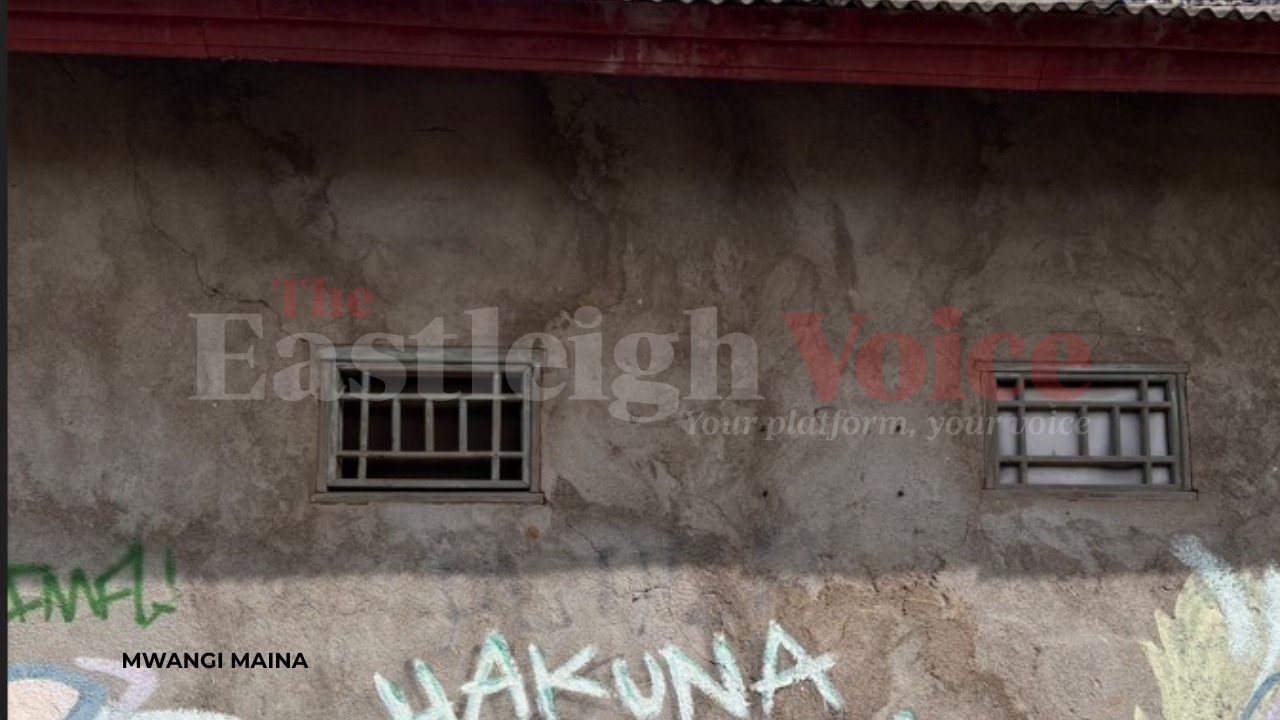

On Gili Trawangan, a car-free, motorcycle-free island off Indonesia’s coast, nearly 4,900 miles from Nairobi, Hakuna Matata is spray-painted on a wall.

It sits untethered from its linguistic roots, but firmly attached to an idea: ease, leisure and escape.

Swahili is neither spoken nor understood here, but the phrase survives anyway.

This is soft power without a ministry.

Soft power

The late Joseph Nye, who coined the term “soft power” in the late 1980s, argued that influence does not always travel through force or money. It often moves more quietly, through attraction, culture and persuasion.

Soft power works when people want what you represent, not when they are compelled to accept it.

Hakuna matata is a textbook example.

Unlike hard power, which relies on coercion and command, soft power seeps into global consciousness through repetition and appeal. It is the opposite of gunboats and sanctions. One might contrast it with the muscular interventions that have defined modern geopolitics, where power is exercised openly, abruptly and with force.

Soft power, by contrast, smiles, hums and lingers.

Kenya and Tanzania did not export hakuna matata through diplomacy or policy. They exported it through tourism, music and popular culture.

Kenya’s welcoming anthem

In 1982, the Kenyan coastal band Them Mushrooms released “Jambo Bwana”, a welcoming anthem for visitors that casually embedded the phrase. The song was a hit. A year later, the German group Boney M released an English version, “Jambo – Hakuna Matata”, sending the phrase further into global circulation.

Then came the cultural accelerant.

In 1994, the Walt Disney Company released The Lion King, cementing hakuna matata as a global slogan for carefree living. The phrase became inseparable from animated savannahs, musical montages and moral lightness.

That same year, Disney applied to trademark the phrase for use on merchandise. The trademark was approved in 2003 and remains active, narrowly covering apparel that resembles The Lion King branding.

Outrage across East Africa

Still, when the issue resurfaced in 2018, it sparked outrage across East Africa. For many, the idea that a multinational corporation could claim ownership of a common Swahili expression felt like cultural trespass.

The late Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was among the critics. He described the claim as absurd, likening it to trademarking “good morning” or “it’s raining cats and dogs”.

A language, he argued, cannot be owned.

Phrase thrives globally

And yet, the phrase continues to thrive globally, precisely because it has been stripped of context.

On Gili Trawangan, the Indonesian island where The Eastleigh Voice encountered the wall-painted slogan, the phrase has acquired a second life.

A local hotelier, Akip Adnan Maulana, cheerfully admitted he thought hakuna matata was Korean. His colleague guessed Japanese. Neither knew its origin.

Both knew what it meant.

Calm. Escape. Vacation.

That ignorance is not a failure of soft power. It is its success.

Soft power works best when it feels universal, not local.

Global appeal

At home, hakuna matata can sound performative, even clichéd. Abroad, it feels authentic enough to sell serenity.

Its global appeal depends not on accuracy, but on atmosphere.

No ministry planned this. No strategy paper approved it. No ambassador signed it off.

And yet a Swahili phrase now decorates walls, T-shirts and tourist lodges across the world, carrying with it an idea of Africa that is gentle, joyful and uncomplicated.

Soft power, it turns out, travels fastest when it forgets where it came from.