For more than a decade, the persecution of Christians in northern Nigeria unfolded in full public view. From around 2010, the pattern became unmistakable. Churches were attacked. Christian communities were overrun. Villages were emptied. Worshippers were slaughtered in spaces once thought sacred. Survivors spoke with painful consistency. Names of places recurred with dreadful familiarity. What changed was the stubborn refusal by influential sections of the media and parts of the human rights community to describe these events for what they were. Violence that bore the clear marks of religious targeting was persistently flattened into the language of farmers-herders clashes, a phrase that drained the blood from reality and replaced it with absurdity and abstraction.

The narrative wasn’t innocent. It was carefully cultivated at home and repeatedly exported abroad. Several activists embarked on trips to the United States, briefing think tanks, policymakers, and advocacy groups with a story that denied any systematic persecution of Christians. According to them, Nigeria was merely suffering from climate stress, population pressure, and competition over land. Religion, they insisted, was a mere red herring.

The effect was devastating. Victims were rendered faceless. Perpetrators were dissolved into sociological fault lines. Moral responsibility disappeared into jargon. The presidency of Goodluck Jonathan took its cue from this framing and reinforced it. Official statements echoed the language of balance and communal tension even as massacres mounted. But the underlying refusal to name persecution remained intact. What could not be named could not be confronted. What could not be confronted metastasised. Under General Muhammadu Buhari, this denial acquired a sharper edge.

The persistent downplaying of the religious character of the violence coincided with policies and silences that promoted and defended the presence of ascendant Fulani hegemony everywhere. Attacks followed attacks with little consequence. Security responses were lethargic or curiously absent. Communities learned, through bitter experience, that their lives ranked low in the reckoning of the state. Still, the same old vocabulary was pushed out on wheelbarrows by rabid Fulani hegemons. Farmers and herders. Clashes. Cycles of reprisal. Anything except persecution.

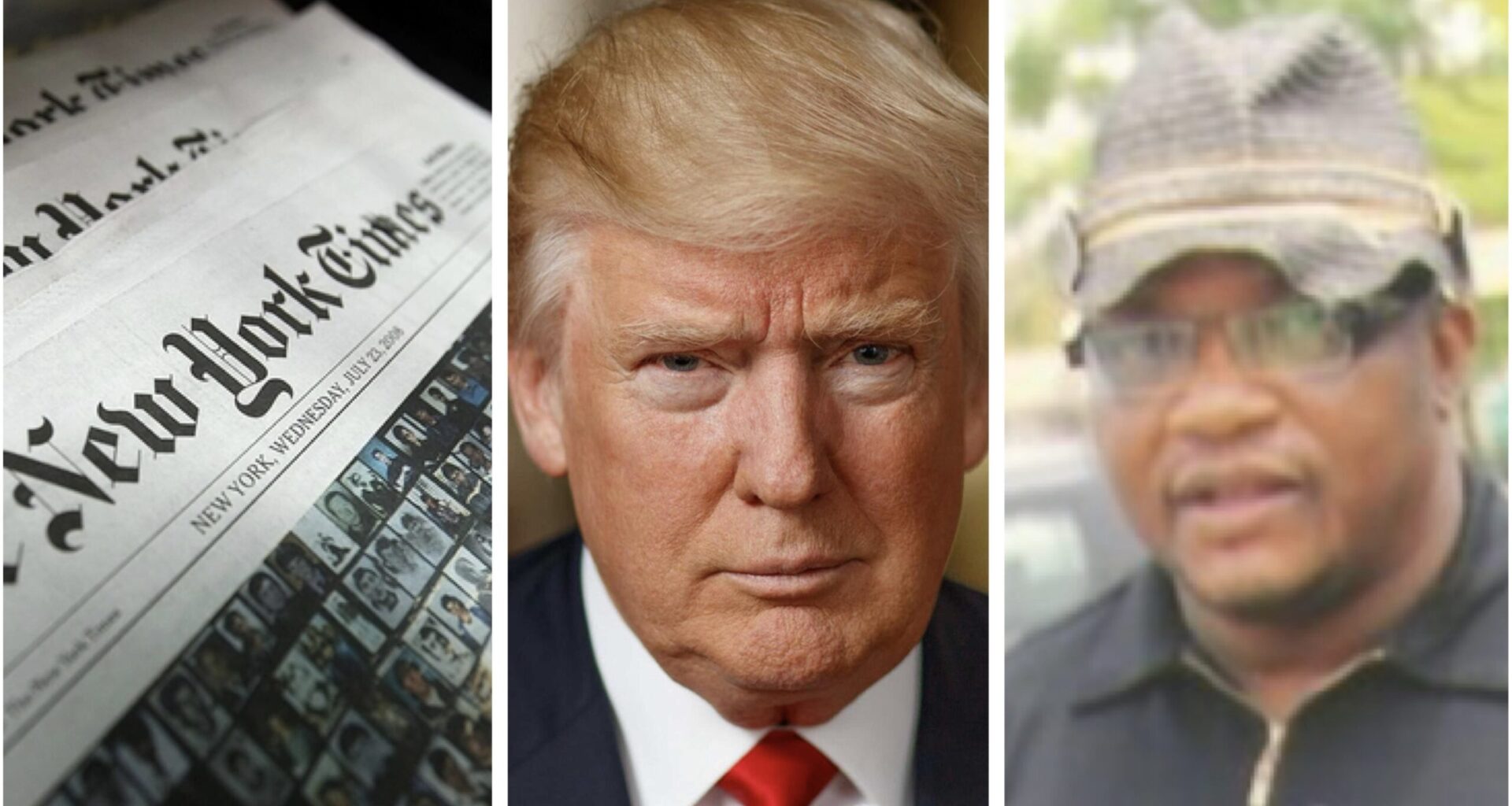

The recent revelation by The New York Times exposes a striking irony. For years, Christians in northern Nigeria were slaughtered, their communities devastated, yet the world, the New York Times included, consistently failed to recognise the reality for what it was: violence that bore the unmistakable marks of targeted persecution was repeatedly described as farmers-herders clashes, abstracted into statistics and turned into narratives that avoided the inconvenient truth.

Meanwhile, Emeka Umeagbalasi, described by the New York Times as an ordinary “screwdriver salesman”, documented the killings with painstaking detail, reporting what the media overlooked and what powerful institutions dismissed. The New York Times’s suggestion that the intelligence used by the United States to strike terrorists reportedly emerged from Emeka Umeagbalasi’s reports for Intersociety carries a grim irony that would not be lost on Kafka. The idea that an ordinary screwdriver salesman could generate information that travels upward through the layers of global power unsettles those who have invested years in denial. It exposes how threadbare their certainties really were.

There is something profoundly Kafkaesque in this imagery of the salesman. Like Gregor Samsa before his metamorphosis, the salesman inhabits the margins of society, overlooked and underestimated, yet uniquely positioned to see what grand institutions often miss. In Kafka, the travelling salesman is crushed by bureaucracy, reduced to an inconvenience and stripped of dignity. Here, the same modest figure unsettles bureaucracy. His bird’s-eye documentation of survivors’ testimonies from burnt-out communities, as reflected in media reports, exposed the state’s persistent lethargy.

Here’s the irony. In a world governed by drones and advanced espionage intelligence, history still turns on the notes, movements, and moral insistence of an unremarkable man carrying his wares. It is, therefore, deeply dishonest for those who spent years denying the persecution of Christians in northern Nigeria to now claim that the United States acted on the report of Emeka Umeagbalasi, who did not invent the crisis. He documented an issue that had been visible for years. His report did not conjure genocide into existence. It bore witness to what survivors had been saying all along. To suggest otherwise is to reframe denial as a convenient narrative of ethnic manipulation.

The attempt to describe Umeagbalasi primarily as a screwdriver salesman is not accidental. It is a strategy aimed at trivialising the discourse and dehumanising the man by reference to how he earns his living. It implies that truth requires elite certification and that moral authority flows only from institutions, grants, and polished accents. It reveals an elitism that has long poisoned Nigeria’s public conversation. As though suffering only becomes real when endorsed by the properly credentialed. What truly unsettles the deniers is not the man’s occupation, but his refusal to participate in the great lie. He did not rename persecution as misunderstanding.

He did not subject the testimonies of victims to the comfort of grant-seeking activists and their friends in the lobbying corridors of the West. He did not wait for permission to insist that what was happening was wrong. That his work could eventually draw global attention is an indictment of those who chose silence or distortion when it mattered most. The shift in narrative did not occur because the violence suddenly changed character. It occurred when Donald Trump re-entered the White House and proved willing to call things by their names. Under his administration, Christian persecution is now openly acknowledged. Nigeria appeared on his watch list as a country of particular concern. The language of genocide entered official discourse. The facts had always been there. What changed was the willingness to confront them without euphemism.

This should prompt a hard reckoning within the human rights community. Advocacy that bends facts to fit fashionable claims does grave harm. When identity is erased in the name of balance, victims disappear. When ideology trumps testimony, suffering becomes negotiable. The farmers-herders’ narrative did not merely mask the reality; it delayed accountability, emboldened killers, and taught persecuted Christians that their pains were inconvenient to powerful conversations. The real question is not whether a screwdriver salesman supplied intelligence to the United States. The real question is why it took more than a decade for the persecution of Christians to be acknowledged for what it truly was. Why were those who spoke early dismissed or ridiculed?

Why did victims have to wait for a shift in geopolitics before their reality was recognised? These are uncomfortable truths, but they cannot be ignored. Truth does not require elite permission to exist. It requires witnesses. Sometimes those witnesses carry titles and institutional backing. Sometimes they carry screwdrivers and notebooks. The task remains unchanged: to see, to bear witness, to insist, and to remind a world practised in evasion that even the most elaborate falsehoods unravel before the quiet persistence of an ordinary human being who refuses to look away. Call that human being Emeka Umeagbalasi, or Gregor Samsa.

Abdul Mahmud, a human rights attorney in Abuja, writes weekly for The Gazette