It wasn’t what the miners had come for. In Namibia’s far southwest, near the edge of the Atlantic, workers clearing sand in a high-security diamond concession struck something unexpected. Timbers. Metal. Then gold.

The area, known as the Sperrgebiet, had been closed to the public since the early 1900s. Thick fog often blankets the coast, and little grows inland. But beneath the desert’s surface, something had rested quietly for nearly five centuries, unknown, untouched, and remarkably intact.

At first, few understood what had been found. Miners were there for diamonds, not archaeology. But within hours, the site was sealed off. Excavations began. What emerged over the following weeks would come to be recognised as one of the most important maritime discoveries ever made on the African continent.

The shipwreck, later identified as the Bom Jesus, a Portuguese carrack lost in 1533, held not only artefacts but insight. Ivory. Coinage. Ingots stamped with the seal of German bankers. The find now forms a tangible link between early modern Europe, West Africa and the Indian Ocean trading world.

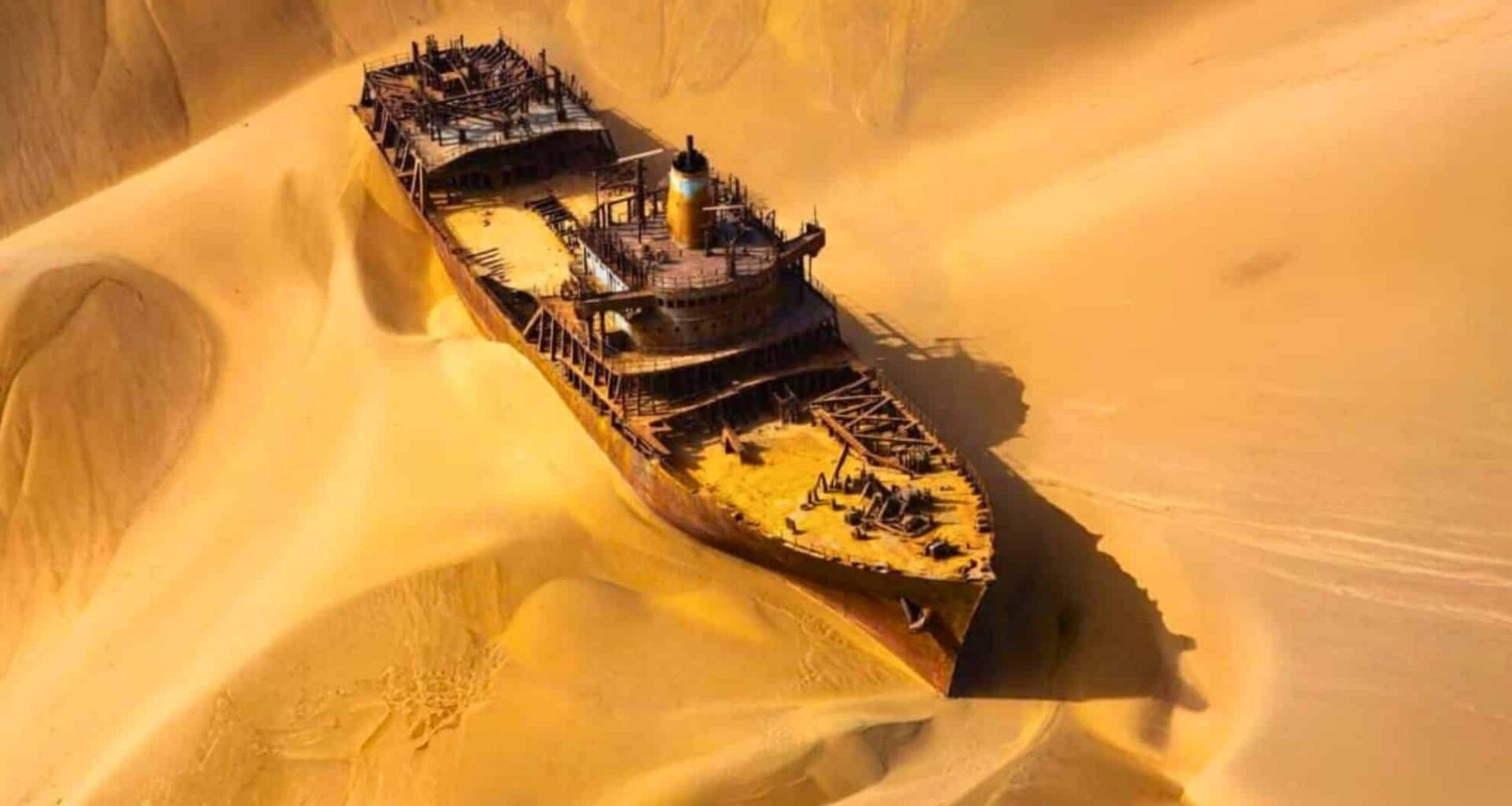

Found Inland, Sealed by Sand, Not Salt

The wreck was discovered in April 2008 near Oranjemund, inside a concession operated by Namdeb, a joint enterprise between the Namibian government and De Beers Group. Mining was suspended immediately after the discovery.

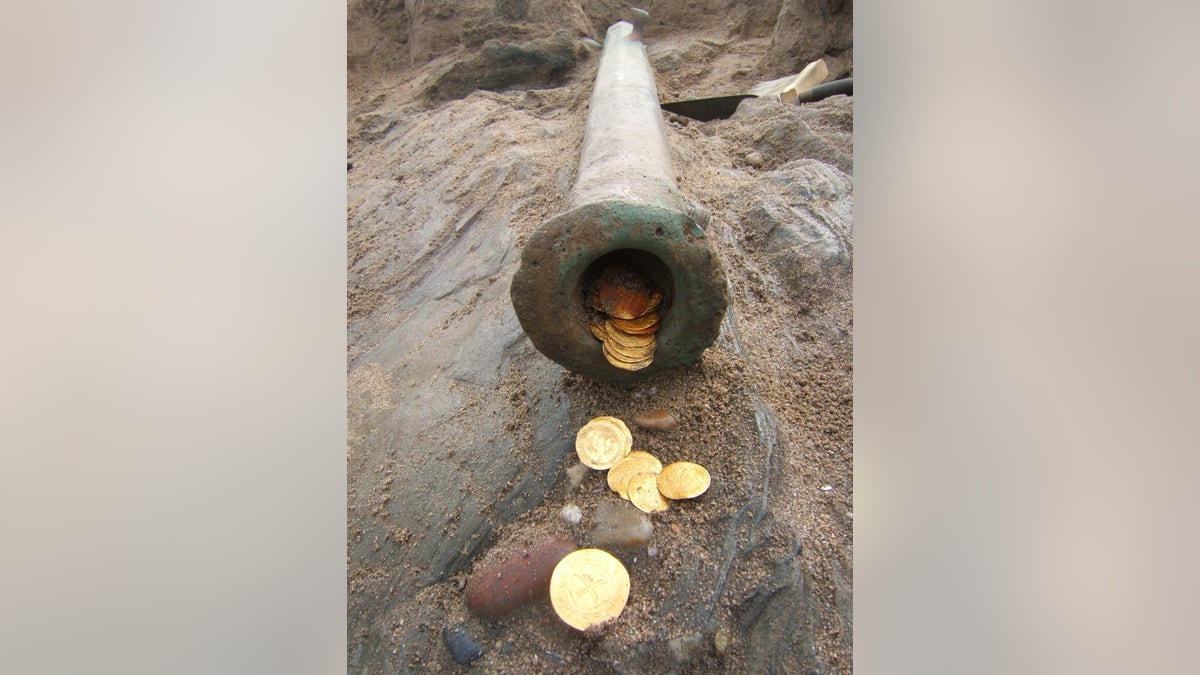

One of the gold coins discovered in the Namibian shipwreck. Credit: Dieter Noli

One of the gold coins discovered in the Namibian shipwreck. Credit: Dieter Noli

The site lay several hundred metres from the current shoreline. The position confused early observers, but analysis later showed that over centuries, wind-driven sediment had pushed the coastline westward. The Namib Desert had slowly swallowed what once was beach.

A 2014 study published in Quaternary International on desert geomorphology and palaeoclimate confirmed that the hyper-arid climate and stable dune layers helped preserve even fragile materials like timber, textile and rope, which is unusual in shipwreck archaeology.

This preservation made identification possible. Among the ship’s artefacts were Portuguese português and Spanish excelente gold coins minted in the early 16th century. The mix of currencies, combined with records from the Portuguese royal archives and the visual chronicle Memória das Armadas, pointed to a specific ship in a specific fleet: the Bom Jesus, captained by Dom Francisco de Noronha, one of seven vessels that left Lisbon in March 1533 under the command of Dom João Pereira.

Gold coins and a cannon discovered in the Namibian shipwreck. Credit: Dieter Noli

Gold coins and a cannon discovered in the Namibian shipwreck. Credit: Dieter Noli

Historical documents cited by maritime historian Alexandre Monteiro confirm that the Bom Jesus was listed as “perdido” (lost) not long after the fleet passed the Cape of Good Hope. Monteiro, in his peer-reviewed study on early Iberian maritime trade, traced the ship’s financial and logistical background, revealing joint investment between Lisbon and Seville. No survivors were documented. No message had reached Lisbon.

A Cross-Continental Cargo

The ship’s contents made clear this was not a naval or exploratory voyage. It was commercial. A total of over 2,000 gold coins were recovered, mainly Portuguese but also Castilian — excelentes from Seville rarely seen on Portuguese ships of the era. Monteiro’s archival research suggests that 20,000 Portuguese cruzados were transferred to Spanish backers weeks before the voyage departed.

The wreck also held 22 tonnes of copper ingots, many stamped with the trident seal of the Fugger banking house, based in Augsburg. The Fuggers were among Europe’s most powerful financiers at the time, with a history of funding long-distance trade and royal expeditions.

Cargo recovered from the wreck also included at least 40 elephant tusks from West Africa, packed and prepared for shipment. These were likely destined for Indian Ocean ports, such as Goa, where ivory played a central role in commerce between Portuguese, Indian, and Arab traders.

A coin and rosary beads discovered in the Namibian shipwreck. Credit: Dieter Noli

A coin and rosary beads discovered in the Namibian shipwreck. Credit: Dieter Noli

“This is not just an archaeological site; it’s a sealed economic time capsule from the Age of Discovery,” said Dr Bruno Werz, director of AIMURE (African Institute for Marine and Underwater Research, Exploration and Education), in a summary cited by Daily Galaxy’s coverage of the discovery. “We’re dealing with a ship that tells the story of early globalization through physical evidence, not fragments, but full systems.”

One Toe Bone, and Unanswered Questions

More than 300 crew members, including sailors, clergy and soldiers, were likely aboard. Yet archaeologists found only one partial human remain: a single toe bone, still inside a shoe. This lone find suggests some may have reached land.

Chief archaeologist Dr Dieter Noli, who led the excavation and has documented his work through Namibiana, noted that the nearby Orange River, roughly 25 kilometres south, might have been accessible to survivors. In interviews and field notes, Noli stated that the desert was not entirely barren and may have supported life-saving foraging or contact with San communities.

Whether anyone reached safety is unknown. No burial sites or personal belongings linked to crew have been discovered in the area. Oral histories have yet to yield any clues.

No Legal Contest Over Ownership

Despite the gold and ivory, there was no legal dispute over the shipwreck. The site lies within Namibia’s territorial zone and under the terms of the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage, the wreck and its cargo fall under national jurisdiction.

Portugal, the ship’s flag state and a signatory to the convention, chose not to assert a claim. Monteiro, in a National Geographic report, praised the approach. “There’s no question the wreck is Namibian. And the country has acted with professionalism and vision in managing it.”

Namdeb suspended mining around the site and provided logistical and technical support during excavation. Artefacts have since been secured in state custody. Namibian officials have announced plans for a permanent maritime museum in Oranjemund, which will house the ship’s recovered materials and serve as a regional research centre for marine archaeology.