(AI image generated using ChatGPT) While Somalia has resurfaced in headlines because of events unfolding in the United States, the far deeper story lies closer to home. The events that have unfolded in the Horn of Africa for more than seven decades have rarely garnered sustained global attention.Somalia is often dismissed as a “failed state”, but the phrase obscures more than it explains. What exists today is not simply absence or collapse, but accumulation: layers of unresolved conflict built atop climate shocks, poverty, displacement and chronically fragile governance. Each crisis reinforces the next. When rains fail, hunger spreads. When hunger spreads, violence and displacement follow. And when the state cannot protect or provide, armed groups, clan militias and criminal networks step in to fill the void.In recent years, this cycle has tightened. Al-Shabaab continues to strike even as international forces patrol the capital. Nearly half the population now depends on humanitarian aid to survive. Yet Somalia’s emergency is neither sudden nor accidental. It is the outcome of decades of political choices made by dictators and warlords, foreign powers and local elites. To understand Somalia today, one must look back at how it unravelled.

(AI image generated using ChatGPT) While Somalia has resurfaced in headlines because of events unfolding in the United States, the far deeper story lies closer to home. The events that have unfolded in the Horn of Africa for more than seven decades have rarely garnered sustained global attention.Somalia is often dismissed as a “failed state”, but the phrase obscures more than it explains. What exists today is not simply absence or collapse, but accumulation: layers of unresolved conflict built atop climate shocks, poverty, displacement and chronically fragile governance. Each crisis reinforces the next. When rains fail, hunger spreads. When hunger spreads, violence and displacement follow. And when the state cannot protect or provide, armed groups, clan militias and criminal networks step in to fill the void.In recent years, this cycle has tightened. Al-Shabaab continues to strike even as international forces patrol the capital. Nearly half the population now depends on humanitarian aid to survive. Yet Somalia’s emergency is neither sudden nor accidental. It is the outcome of decades of political choices made by dictators and warlords, foreign powers and local elites. To understand Somalia today, one must look back at how it unravelled.

Decades of upheaval: How did we get here?

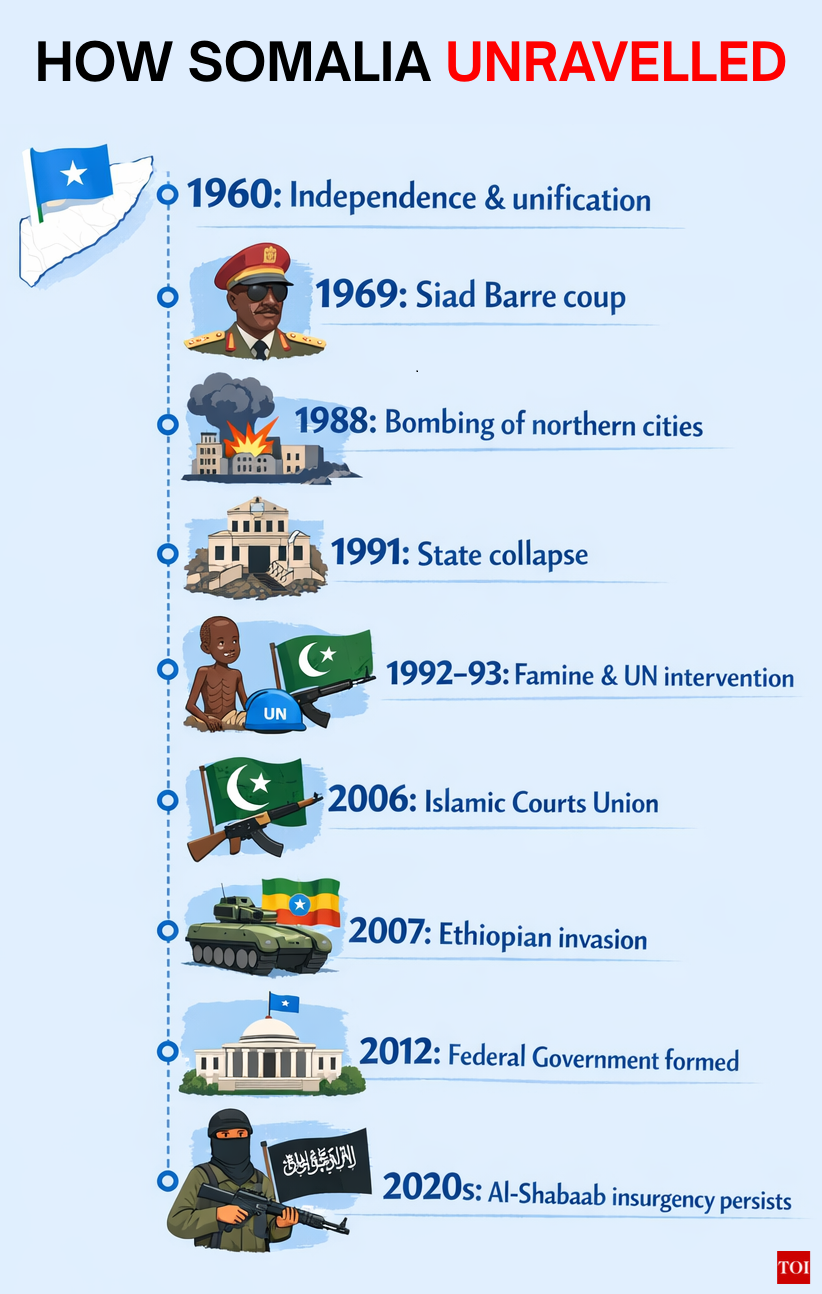

After World War II, Somalia briefly flourished under British and Italian trusteeship. When British Somaliland and Italian Somalia united in 1960, the new Republic of Somalia started as a parliamentary democracy. However, that era of optimism ended on October 21, 1969, when Major General Mohamed Siad Barre led a military coup. Barre proclaimed a socialist state and ruled through a tight dictatorship for the next 22 years.  He nationalised industry and allied with the Soviet bloc, later with the United States, but his regime grew brutally repressive. Barre distrusted Somalia’s clan structure (Somalis traditionally organise by clan) and sought to “eradicate” clan loyalties. In practice, this meant empowering a narrow inner circle and mercilessly crushing dissent. For example, in 1988, his regime bombed and besieged northern cities, resulting in up to 200,000 civilian deaths among the Isaaq clan.By 1991, Barre’s rule had exhausted the country. Allied militia forces from rival clans banded together and overthrew him in early 1991. But instead of unity, Somalia descended into chaos. The central government collapsed and armed clan factions turned on each other. This civil war was accompanied by a man-made famine in 1992, killing hundreds of thousands. A multinational relief and peacekeeping mission arrived in 1992–93, but it ended in failure: after US troops withdrew following the 1993 “Black Hawk Down” battle in Mogadishu, the international community largely pulled back. For most of the 1990s, there was no functioning national government at all.Somaliland (in the northwest) and Puntland (in the northeast) each set up their own administrations. Somaliland even declared independence (recognised only by Israel). Elsewhere, the fighting turned Somalia into a patchwork of militias and warlords. With no police or courts, many Somalis increasingly turned to local elders or Islamist sharia courts for justice. By the early 2000s, dozens of local sheikhs ran sharia tribunals. In 2006, several of these courts united to form the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), which seized control of Mogadishu and parts of southern Somalia. The ICU imposed strict Islamic law and brought a measure of order – but also alarmed neighbouring Ethiopia. In December 2006, Ethiopia (backed by the US) sent troops into Somalia to prop up a weak transitional government. The ICU was driven out of Mogadishu by early 2007. Its remnants splintered, with the hardline wing reforming as al-Shabaab, an al Qaida–linked insurgent group.

He nationalised industry and allied with the Soviet bloc, later with the United States, but his regime grew brutally repressive. Barre distrusted Somalia’s clan structure (Somalis traditionally organise by clan) and sought to “eradicate” clan loyalties. In practice, this meant empowering a narrow inner circle and mercilessly crushing dissent. For example, in 1988, his regime bombed and besieged northern cities, resulting in up to 200,000 civilian deaths among the Isaaq clan.By 1991, Barre’s rule had exhausted the country. Allied militia forces from rival clans banded together and overthrew him in early 1991. But instead of unity, Somalia descended into chaos. The central government collapsed and armed clan factions turned on each other. This civil war was accompanied by a man-made famine in 1992, killing hundreds of thousands. A multinational relief and peacekeeping mission arrived in 1992–93, but it ended in failure: after US troops withdrew following the 1993 “Black Hawk Down” battle in Mogadishu, the international community largely pulled back. For most of the 1990s, there was no functioning national government at all.Somaliland (in the northwest) and Puntland (in the northeast) each set up their own administrations. Somaliland even declared independence (recognised only by Israel). Elsewhere, the fighting turned Somalia into a patchwork of militias and warlords. With no police or courts, many Somalis increasingly turned to local elders or Islamist sharia courts for justice. By the early 2000s, dozens of local sheikhs ran sharia tribunals. In 2006, several of these courts united to form the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), which seized control of Mogadishu and parts of southern Somalia. The ICU imposed strict Islamic law and brought a measure of order – but also alarmed neighbouring Ethiopia. In December 2006, Ethiopia (backed by the US) sent troops into Somalia to prop up a weak transitional government. The ICU was driven out of Mogadishu by early 2007. Its remnants splintered, with the hardline wing reforming as al-Shabaab, an al Qaida–linked insurgent group.

The struggle for governance

Throughout Somalia’s collapse, clan dynamics have remained central. The country’s four main clans and smaller sub-clans vie constantly for resources and power. Barre’s fall in 1991 unleashed open clan warfare, and to this day, Somali politics is often about negotiating clan shares of power. For example, the post-2012 political system codified a “4.5 formula” under which seats in parliament and top jobs are allocated by clan. The CIA World Factbook notes that even in recent elections, members of parliament were chosen by agreements among elders, not by one-person-one-vote; the House of the People in 2012 was “appointed in September 2012 by clan elders”, and a new parliament in 2021 was similarly arranged by clans. In practice, this means no Somali government has ever rested on a truly national mandate. Weak federal institutions struggle to unify the country.  Local clan militias and informal forces abound. As of 2021, large parts of rural Somalia remained beyond government control, often under the sway of clan-based militia leaders or the insurgent al-Shabaab. Even the Somali National Army (SNA) is underfunded and fragmented, absorbing some clan militias but lacking discipline. The result is chronic instability: rivalry between the central state and semi-autonomous regions (like Puntland) or disputed areas, as well as periodic flare-ups of fighting. For example, rivalries triggered long election delays in 2021–22, and conflicts between federal and regional authorities have repeatedly broken out. In short, governance remains fragile, undermined by clan feuds and years without a strong centre.

Local clan militias and informal forces abound. As of 2021, large parts of rural Somalia remained beyond government control, often under the sway of clan-based militia leaders or the insurgent al-Shabaab. Even the Somali National Army (SNA) is underfunded and fragmented, absorbing some clan militias but lacking discipline. The result is chronic instability: rivalry between the central state and semi-autonomous regions (like Puntland) or disputed areas, as well as periodic flare-ups of fighting. For example, rivalries triggered long election delays in 2021–22, and conflicts between federal and regional authorities have repeatedly broken out. In short, governance remains fragile, undermined by clan feuds and years without a strong centre.

Extremism and terror: The rise of Al-Shabaab

The vacuum of power allowed militant Islamists to flourish. Al-Shabaab emerged from the ruins of the ICU. It is now Somalia’s deadliest threat. According to the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), al Shabaab “remains one of al Qaida’s strongest and most successful affiliates”. It openly seeks to overthrow Somalia’s federal government and impose a strict Islamist state over all Somali regions. In practice, al Shabaab has waged a guerrilla war since the mid-2000s. By 2011, it controlled key cities like Mogadishu and the southern port of Kismayo, but African Union troops and Somali forces pushed it out of the cities by 2012. The group has since reverted to insurgency – carrying out frequent suicide bombings and ambushes in Mogadishu and beyond, as well as periodic raids into Kenya and Ethiopia.Despite great multinational efforts, al Shabaab remains capable. Its attacks surged in 2022–23. For instance, data show that conflict-related killings surged to their highest levels in over a decade by late 2022, the highest fatality rate in Somalia in over a decade. Bombings at hotels, markets and checkpoints in Mogadishu have become tragically commonplace, and high-profile attacks against civilians continue. In early 2024 alone, al Shabaab claimed dozens of victims. (An associated minor terror group, Islamic State–Somalia, has also appeared in Puntland since 2015, but it remains far smaller.)The ongoing terror war has a heavy toll on Somalis. It drives people from their homes, destroys farms and markets, and discourages investment. It also complicates aid delivery: al-Shabaab routinely blocks or raids humanitarian convoys. In short, Somalia’s security crisis and jihadist insurgency feed directly into its other woes, making any recovery much harder.

Piracy: Lawlessness at sea

In Captain Phillips, audiences saw one dramatic offshoot of Somalia’s instability: piracy born of lawlessness and frustration on its seas.In the mid-2000s, another lawless phenomenon grabbed headlines: Somali piracy. Thousands of unruly fishing vessels (and later cargo ships) were hijacked off Somalia’s coast between 2005 and 2012. At its peak, pirates were capturing tens of ships per year and extorting millions in ransom. By 2011 over 200 attacks had been reported (including 28 successful hijackings). International naval patrols, armed guards on ships and the decline of Somalia’s Islamic Courts reduced piracy sharply. One study noted that hijackings fell from 47 vessels in 2010 to just 5 in 2012. By 2020 the international Maritime Bureau had recorded almost zero successful attacks from Somalia’s waters.However, piracy has never fully disappeared. Although dramatic media attention faded, small Somali piracy networks have persisted. After 2015, pirates shifted tactics (e.g. attacking fishermen and aid vessels). In 2022–23, fresh incidents re-emerged off Puntland’s coast, reminding the world that the roots of piracy – lawlessness, poverty and impunity – remain. Industry experts warn that without continued vigilance, Somali pirates could grow bolder again. In any event, the piracy saga illustrated how Somalia’s breakdown reverberated globally: ships started arming crews, nations sent fleets to patrol the Horn of Africa, and world freight costs even reflected the danger of these “lawless waters.”

Economy and poverty

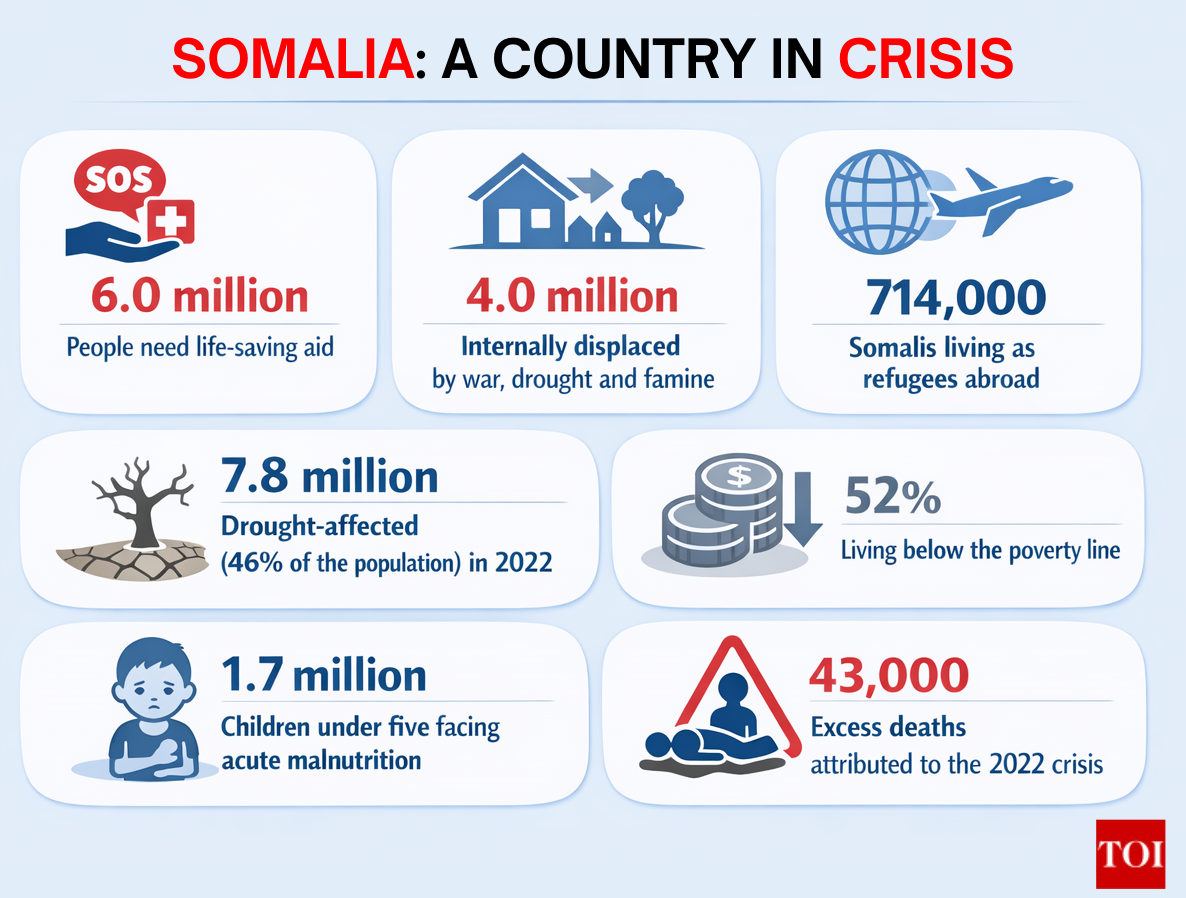

Somalia’s economy has never recovered from years of war. Formal GDP is tiny – only about $13 billion (PPP) in 2020 – and GDP per capita is roughly US$800. The country has no oil, factories or significant industry. Instead, 60%–70% of GDP comes from agriculture and livestock (the economy’s traditional base). Services (including telecoms and money transfers) add another 30%. Critically, the Somali government collects almost no tax revenue: it has no reliable system of commerce or customs. The CIA Factbook reports that Somalia essentially runs on an informal private economy and external aid. Remittances from the Somali diaspora are a lifeline. Somalis living abroad (in the Gulf states, North America, Europe, etc.) send an estimated $1.6–$1.8 billion per year back home – nearly 20% of GDP. Telecom companies (ranging from mobile operators to money-transfer hawalas) similarly sprang up largely outside government oversight, filling basic needs that no state was providing.The upshot is chronic underdevelopment. Roads, schools and hospitals are scarce. Most Somalis survive on a few dollars a day. According to UNDP, about 52–54% of Somalis live below the poverty line. More worryingly, three-quarters of Somali youth have no jobs. The country’s GDP grew only about 2–3% per year in the 2010s, barely enough to keep pace with population growth. With roughly 80% of Somalis under age 35, this means a rapidly expanding generation with few opportunities. In short, Somalia’s economy is stagnating: insecurity and weak governance deter investment, and the local economy cannot absorb more than a fraction of the workforce.

The human cost

Faced with such hardship, many Somalis have fled. Regional and international migration is a major pressure valve. By late 2023, there were over 714,000 Somali refugees registered abroad – mostly in neighbouring countries like Kenya, Ethiopia and Yemen. (Somaliland hosts many of these refugees in sprawling camps.) Within Somalia, nearly 4 million people are displaced internally, many of them shunted into makeshift IDP camps around cities like Mogadishu and Baidoa.Each year, thousands of Somalis undertake harrowing journeys – across the Gulf of Aden to Yemen (a war zone itself), or across the Sahara towards North Africa and Europe. The death toll is high. For example, one 2016 Mediterranean shipwreck claimed about 500 lives; Reuters reported that roughly 190 of those were Somali nationals. Remittances from those abroad help families survive, but the social cost is immense: Somali society has been fragmented by decades of out-migration.

The road ahead

On paper, Somalia has made some progress. In 2012, an internationally-brokered provisional constitution created the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) in Mogadishu. Since then, there have been several parliamentary and presidential elections (albeit with frequent delays). In July 2024, Somalia was even included for the first time in the UN’s Human Development Index, a sign of emerging data collection and state-building.Yet the challenges remain enormous and deeply entwined. UNDP notes that even as Somalia “enters a hopeful future”, 80% of the population still “struggle to meet daily needs”. Recurring natural disasters (droughts, floods, locusts) continue to destroy crops and herds. The security threat of al-Shabaab endures. And no major political constituency in Somalia has yet accepted the government of Mogadishu as the sole legitimate authority. International partners (the UN, African Union, donor states) pour in aid and troops (currently 20,000 AMISOM forces still patrol Somalia), but their impact is limited if domestic governance is not reformed.Somalia’s plight can be seen as a negative feedback cycle: weak or illegitimate governance makes instability and clan violence more likely, which in turn discourages economic development and leaves people vulnerable to drought and hunger. Somalia’s crisis is often treated as an endless emergency, but it is better understood as a warning. Decades of fractured governance, unresolved conflict and neglect have turned manageable stresses into permanent shocks. Drought becomes famine. Political rivalry becomes an armed confrontation. Lawlessness on land spills into lawlessness at sea. Yet Somalia’s story is not fixed. Its people have endured state collapse, extremism and climate disasters while preserving social networks that continue to sustain daily life. The question is not whether Somalia can be rebuilt, but whether its leaders and international partners are willing to move beyond short-term fixes.