Home to just three million people and bigger than Texas, Namibia is the

world’s second least-densely populated country ©Desert Rhino Camp

In the early, honeyed hours of a bone-dry Namibia morning, I thought I was hallucinating. We were driving through Sossusvlei in the Namib, the world’s oldest desert, where the rust-red dunes reach heights of 1,000 ft and sprawl on and on, into the distance and beyond. Suddenly I saw a fan of black and white feathers swirl against the sands, shimmying with all the seductive poise of a performer at the Moulin Rouge. It wasn’t a stray can-can dancer, but an ostrich vigorously windmilling its wings. This contorted mating ritual failed to impress a nearby female but mesmerized those of us witnessing the display from our vehicle.

I hadn’t expected surprise animal encounters to feature on my journey in Namibia. When it comes to assured sightings and wildlife density, neighboring Botswana delivers in spades and, along with the likes of Kenya, Zambia and South Africa, is a more obvious go-to for travelers seeking a conventional safari experience. Namibia, meanwhile – vast, wild and formidable – presents majestic landscapes and an almost primordial serenity that feels increasingly hard to find. Home to just three million people and bigger than Texas, this is the world’s second least-densely populated country (after Mongolia). It feels… empty; wonderfully so. Yet life thrives even in the most unlikely places.

I’d come to Namibia in search of escape, after too many years living in excessive, exhausting cities. I was traveling with the conservation and hospitality company Wilderness, which operates seven camps nationwide. Crucially, in a colossal country with limited infrastructure, it also has its own airline, Wilderness Air, greatly reducing travel time between far-flung lodges.

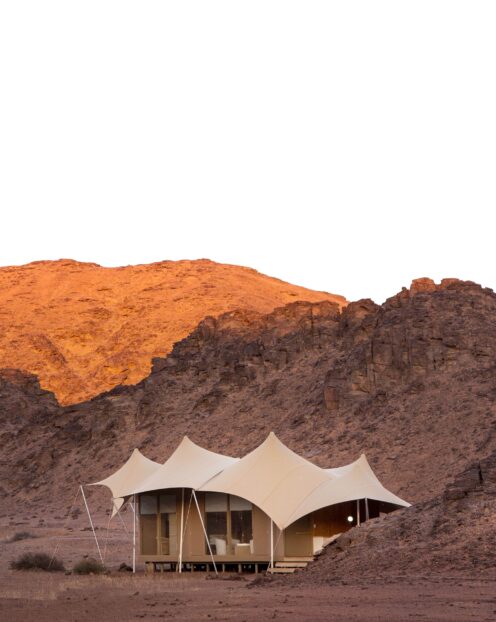

Vast, wild and formidable, Namibia

presents majestic landscapes and an

almost primordial serenity ©Little Kulala

The first of three camps I would visit was the 11-suite Little Kulala, set in the 66,650-acre Kulala Wilderness Reserve and the only lodge with an exclusive-use gate that provides direct access to Sossuvlei’s fabled dunes, perhaps the most recognizable and popular tourist attraction in the country. Setting off at dawn, we reached the site before the crowds (a relative term here, as Namibia welcomed just 560,000 visitors in 2024). We climbed one of those shifting mountains in exhausting heat, before descending to Deadvlei, an arid, silent, unsettling plateau studded with the petrified coal-black carcasses of 900-year- old camel thorn trees.

Later, back at camp, I had a dip in my suite’s private plunge pool and chose to sleep outdoors on the deck’s star bed. With no light pollution, the constellations on show above are spellbinding. I felt completely at peace. Before Wilderness first started operating here in 1996 the area had been used for subsistence goat farming, and the indigenous wildlife was suffering. That situation has since improved, and on subsequent drives we saw herds of oryx, sleek jackals and skittish zebras. Weird haystacks wedged in treetops turned out to be the remarkable communal nests of sociable weavers, the birds inhabiting them in their hundreds.

Preceding my flight to Little Kulala, I had dallied in Windhoek, Namibia’s capital. It’s an inevitable pit stop for international travelers who need to stay overnight after afternoon arrivals or before morning departures, but the city’s charms are few. My night here was spent in an upmarket neighborhood at the boutique The Olive Exclusive, where seven suites overlook olive groves and a leafy valley. This was my first encounter with Namibian hospitality – the kindness of the family-run hotel’s owners was overwhelming. Later, when the trip came to an end, I chose to switch out another night in the city in favor of a stay in Zannier Omaanda. Here, 15 sophisticated thatch-and-clay huts, an infinity pool, spa, airy restaurant and gin bar sit just 30 minutes from the airport in a 22,000-acre conservancy brimming with wildlife. Unlike other parts of the country, abundant animal sightings are pretty much a given here; on our game drive in the dewy light of dawn, it felt surreal to see thriving populations of elephants, lions and meerkats just a few hours before we would return to the familiar admin of passport checks and security.

But that came later. From Little Kulala, I continued to the newly renovated, six-suite Desert Rhino Camp in Damaraland, where guests have access to a 322,560-acre concession that is home to one of the world’s last free-roaming populations of critically endangered black rhinos. Enveloped by ripples of chocolate-brown table-top mountains – a view that matched the splendor of the Grand Canyon – we trundled over a Martian landscape strewn with basalt rocks, and zigzagged up mountains where the air was perfumed with heady drifts of wild sage. With the camp and airstrip shielded from view, my guide and I were completely removed from any sign of civilization. No buildings, no roads, no pylons. Nothing. In the moments when the guide turned off the engine of our 4×4, the silence was total. I wondered if I’d ever been so alone in the world.

Wilderness has a six-suite camp, dubbed Desert Rhino

Camp, in Damaraland ©Desert Rhino Camp

Guests have exclusive access to the Palmwag

Concession, home to one of the world’s

last free-roaming populations of critically

endangered black rhinos ©Desert Rhino Camp

A little earlier on that first evening I saw Katri, a 31-year-old male rhino. On a copper-colored hillock where thickets of poisonous milk bush erupted from the ground like wiry bristles on an old toothbrush, his silvery silhouette stood out against a baby-blue horizon. We crept silently closer on foot. Weighing upwards of 1,800 lbs, blessed with pin-sharp hearing and capable of speeds of up to 35 mph, rhinos can be ferocious. But they’re vulnerable, too, with terrible eyesight and a keen sense of smell that is rendered ineffective if poachers position themselves downwind of their prey.

The next day, we took to the trail again, for what would be a fruitless nine-hour search for another sighting. We broke for a barbecue lunch in a dried riverbed, by gnarled tree trunks and elephant droppings the size of cannonballs. It was only on the way back to camp much later that our trackers confirmed potential activity. We turned onto a hilltop that revealed a sparse sunlit plateau, where a giant rhino that the team incongruously called Dave was slumbering comically in the shade of a shrub half the size of his leathery body.

I continued onwards to Hoanib Skeleton Coast Camp, the 25-minute plane journey far preferable to a day-long drive across aggressive terrains where roads barely exist. I had already become habituated to this absence, and on flights where I did suddenly see a solitary building or maybe a trail of dust rising from a faraway dirt road like pipe smoke, I had to stop myself from shouting: “Look, a house! Wow, a car!” Observing the never-ending unblemished terrains beneath me somehow became a kind of time travel. When signs of modernity intruded, they startled me in the same way I imagine locals would have responded when witnessing the first Model T chug through their towns in the early 1900s.

Elephants are regularly spotted by safari-goers in Namibia ©Hoanib Skeleton Coast Camp

Elephants are among the many majestic wildlife species to be spotted in Namibia.

Escape the hustle and bustle of city life with a stay in the Hoanib Skeleton Coast Camp, which offers complete seclusion ©Hoanib Skeleton Coast Camp

Hobnob Skeleton Coast Camp offers numerous spots for quiet contemplation.

The Hoanib Skeleton Coast Camp is situated in, quite literally, the middle of nowhere ©Hoanib Skeleton Coast Camp

The camps are set up in harsh and forbidding surroundings.

The Wilderness camps in Namibia offer a unique experience in the wild ©Hoanib Skeleton Coast Camp

Conservation and hospitality group Wilderness operates seven luuxry camps in Namibia.

Elephants are among the many majestic wildlife species to be spotted in Namibia.

Hobnob Skeleton Coast Camp offers numerous spots for quiet contemplation.

The camps are set up in harsh and forbidding surroundings.

Conservation and hospitality group Wilderness operates seven luuxry camps in Namibia.

My final camp – beautifully styled, staffed with wonderful local team members, and with a cleverly curated, comforting culinary program, just like its siblings – delivered another testament to nature’s resilience. On a game drive through the surrounding, private Palmwag Concession, I watched a group of giraffes grazing on the slim pickings offered by an impoverished treetop, then turned a corner to discover the carcass of another being devoured by a lion. In these harsh and forbidding surroundings, this apex predator is often reduced to subsisting on beetles and lizards (a unique-to-Namibia behavior that somehow struck me as demeaning for an animal that exists with such ease elsewhere on the continent) and this feast was clearly appreciated. We moved on, past two vultures and a herd of elephants cooling down with a sand bath, to enjoy sundowners in the shade. Removed once again from the rest of humanity, I couldn’t help but notice the brand name on my Namibian-made gin: ‘Desolate.’

But as special and memorable as those moments were, this camp’s chief calling card is its proximity to the unforgiving Skeleton Coast. Often blanketed in dense fogs, it’s notorious for the many ships that have run aground on its craggy shores. Before my return to Windhoek I set out to see it myself via a 12-minute plane journey over golden dunes stretched beneath like butterscotch gelato.

After touchdown, I explored a one-room museum with a hodgepodge of nautical detritus: wooden propellers, rudders and figureheads, sun- bleached animal skulls. A short walk led me to a breezy, sunny bay where a table had been set facing the ocean. There, I drank Chenin Blanc and ate citrus-spritzed paella – a perfect meal and a perfect moment, right there on the edge of the world.

Wilderness offers a nine-night Namibia adventure, starting from $9,890 per person sharing.