Instead of graphics card news, for once we are dealing with a rather cuddly matter, in keeping with the dingy season. Because the history of the domestic cat in Europe is very different from what has long been assumed. A comprehensive analysis of ancient cat genomes shows that the ancestors of today’s domestic cats did not arrive on the continent with Neolithic farmers, but only in ancient times. Earlier finds were long regarded as evidence of very early dispersal, but the genetic data now clearly point in a different direction. Many of the animals interpreted as pets from early Europe were in fact European wildcats whose ancestors had interbred with African hawkcats. It was only much later that the first true representatives of the domesticated lineage were identified, which genetically clearly belong to Felis catus.

A particularly important finding concerns the time of the first dispersal. The oldest true domestic cats in Europe were identified in Sardinia and dated to around 2,200 years ago. This means that they arrived at a time when the Phoenicians maintained an extensive network of trading posts in North Africa, the Mediterranean and the Iberian Peninsula. It seems plausible that cats found their way to the island on Phoenician ships, where they became part of human settlements. The animals offered advantages because they could protect supplies from rodents, while at the same time they spread in port cities and colonies that were in constant exchange with each other.

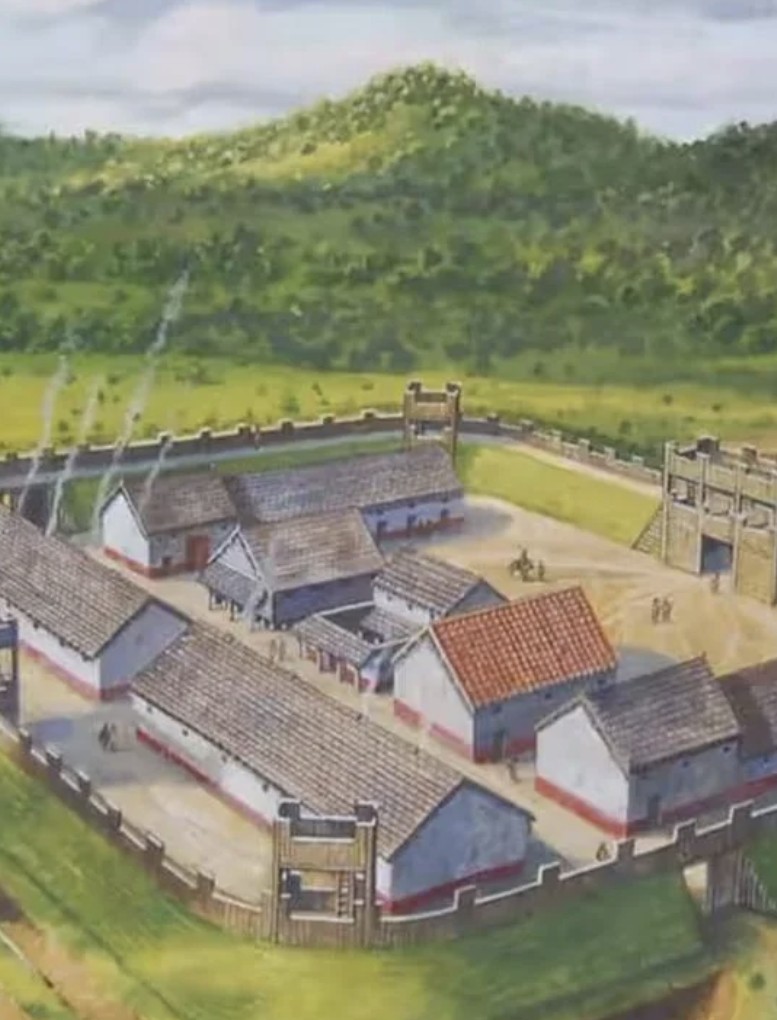

On the European mainland, the spread only began with the Romans. A specimen from the area of present-day Austria, dated around the year 70, is considered the oldest clear evidence to date. The Roman military camps along the Limes and the numerous urban settlements provided ideal conditions for the animals to settle permanently. The Roman presence, which shaped large parts of Europe, ensured that the domesticated cat reached large regions in a short space of time. These genetic lines are among those that later spread across almost the entire continent and form the basis of modern European domestic cats.

Even more important is a look at their origins. New comparisons show that European domestic cats do not originate from the Levant or Anatolia, although people there had close relationships with cats from early on. Instead, the genetic traces lead to North Africa. This shifts the origin of today’s domestic cats to a region that was culturally and historically closely linked to the early trade routes of the Mediterranean region. Various North African societies could have contributed independently to early domestication, which later reached Europe through Phoenician and Roman connections.

The results provide a much more complex picture of the domestication process than previously assumed. Instead of a single region of origin and a single point in time, a multi-layered process emerges in which different cultures and geographical areas were intertwined. It was the interplay of these influences that led to the domestic cat finding its place in people’s everyday lives and becoming one of the most widespread pets in the world over the centuries.

Conclusion

The genetic studies paint a picture that reorganizes the history of domestic cats in Europe. The animals did not arrive on the continent with the first Neolithic farmers, but only via the trade networks of the Phoenicians and later via the far-reaching structures of the Roman Empire. Moreover, their roots do not lie in the Middle East, but in North Africa. This shows how closely human mobility, cultural exchange and animal domestication are linked.

Source: Scinexx.de, Source: Science, American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS)